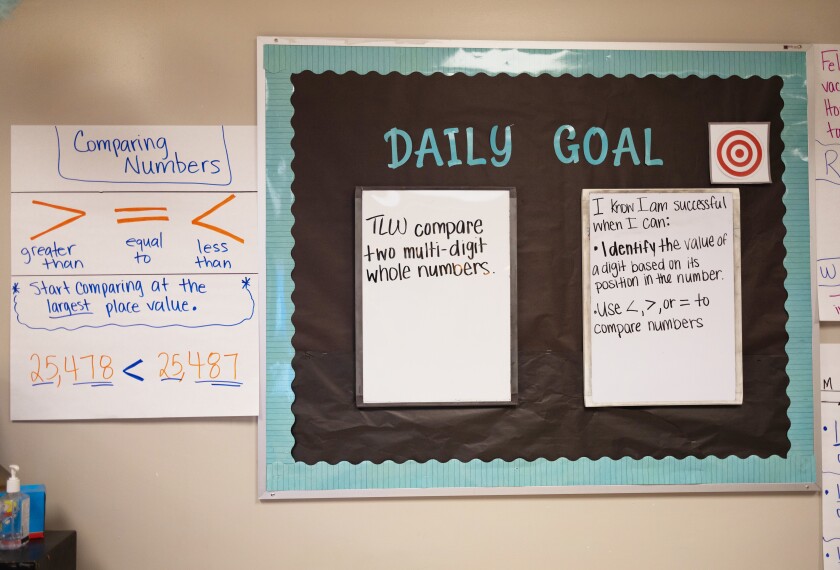

Students’ math scores have plummeted, national assessments show, and educators are working hard to turn math outcomes around.

But it’s a challenge, made harder by factors like math anxiety, students’ feelings of deep ambivalence about how math is taught, and learning gaps that were exacerbated by the pandemic’s disruption of schools.

This week, three educators offered solutions on how districts can turn around poor math scores in a conversation moderated by Peter DeWitt, an opinion blogger for Education Week.

Here are three takeaways from the discussion. For more, watch the recording on demand.

1. Intervention is key

Research shows that early math skills are a key predictor of later academic success.

“Children who know more do better, and math is cumulative—so if you don’t grasp some of the earlier concepts, math gets increasingly harder,” said Nancy Jordan, a professor of education at the University of Delaware.

For example, many students struggle with the concept of fractions, she said. Her research has found that by 6th grade, some students still don’t really understand what a fraction is, which makes it harder for them to master more advanced concepts, like adding or subtracting fractions with unlike denominators.

At that point, though, teachers don’t always have the time in class to re-teach those basic or fundamental concepts, she said, which is why targeted intervention is so important.

Still, Jordan’s research revealed that in some middle schools, intervention time is not a priority: “If there’s an assembly, or if there is a special event or whatever, it takes place during intervention time,” she said. “Or ... the children might sit on computers, and they’re not getting any really explicit instruction.”

2. ‘Gamify’ math class

Students today need new modes of instruction that meet them where they are, said Gerilyn Williams, a math teacher at Pinelands Regional Junior High School in Little Egg Harbor Township, N.J.

“Most of them learn through things like TikTok or YouTube videos,” she said. “They like to play games, they like to interact. So how can I bring those same attributes into my lesson?”

Part of her solution is gamifying instruction. Williams avoids worksheets. Instead, she provides opportunities for students to practice skills that incorporate elements of game design.

That includes digital tools, which provide students with the instant feedback they crave, she said.

But not all the games are digital. Williams’ students sometimes play “trashketball,” a game in which they work in teams to answer math questions. If they get the question right, they can crumble the piece of paper and throw it into a trash can from across the room.

“The kids love this,” she said.

Williams also incorporates game-based vocabulary into her instruction, drawing on terms from video games.

For example, “instead of calling them quizzes and tests, I call them boss battles,” she said. “It’s less frightening. It reduces that math anxiety, and it makes them more engaging.

“We normalize things like failure, because when they play video games, think about what they’re doing,” Williams continued. “They fail—they try again and again and again and again until they achieve success.”

3. Strengthen teacher expertise

To turn around math outcomes, districts need to invest in teacher professional development and curriculum support, said Chaunté Garrett, the CEO of ELLE Education, which partners with schools and districts to support student learning.

“You’re not going to be able to replace the value of a well-supported and well-equipped mathematics teacher,” she said. “We also want to make sure that that teacher has a math curriculum that’s grounded in the standards and conceptually based.”

Students will develop more critical thinking skills and better understand math concepts if teachers are able to relate instruction to real life, Garrett said—so that “kids have relationships that they can pull on, and math has some type of meaning and context to them outside of just numbers and procedures.”

It’s important for math curriculum to be both culturally responsive and relevant, she added. And teachers might need training on how to offer opportunities for students to analyze and solve real-world problems.

“So often, [in math problems], we want to go back to soccer and basketball and all of those things that we lived through, and it’s not that [current students] don’t enjoy those, but our students live social media—they literally live it,” Garrett said. “Those are the things that have to live out in classrooms right now, and if we’re not doing those things, we are doing a disservice.”