Almost three-quarters of high school students think that they can be good at math if they work hard, but fewer say they follow through with that effort when the work gets challenging, according to a new national survey. Less than half feel comfortable asking questions when they don’t understand something.

The results from YouthTruth, a nonprofit that surveys K-12 students and families, demonstrate the perspectives of almost 90,000 high school students toward math, across 62 districts in 14 states. The findings represent the racial/ethnic breakdown of students across the country.

The results highlight American teenagers’ deep ambivalence about how math is taught in schools. While most think that it’s an important subject to learn, they’re often uninterested in the work that they’re given in classes, which they see as disconnected from math’s real-world applications.

“Schools are not effectively showing them why formal mathematics is important. They’re not connecting it to their career or real-world experience,” said Jen de Forest, YouthTruth’s director of organizational learning and communications. “We’re leaving all of their motivation un-sparked.”

The survey comes as U.S. students’ math skills have fallen in the wake of the pandemic, and as debates about how best to engage kids in the subject have grown louder.

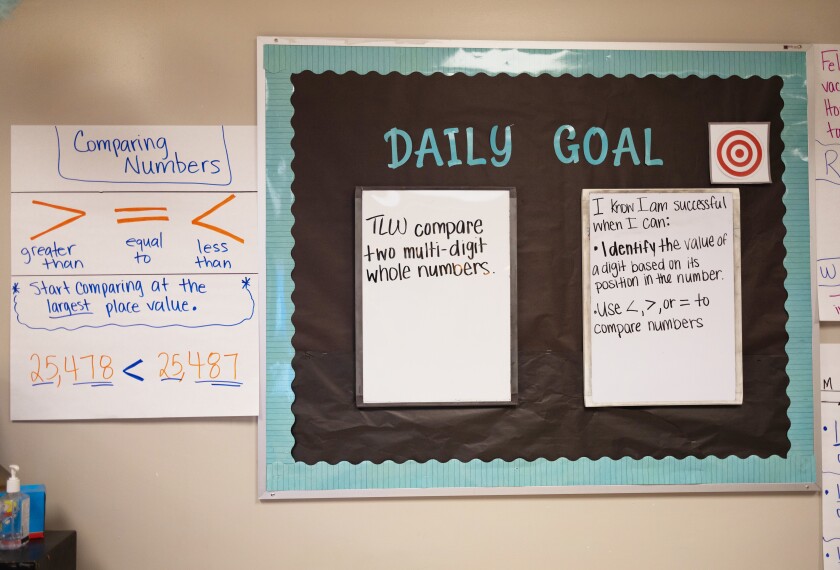

Leading organizations in the field, like the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, have argued that schools should help students develop positive identities as math learners and demonstrate that math can help solve everyday problems.

But some attempts to emphasize math’s applied uses in this way have faced pushback.

In California, for example, the state’s new math framework suggests that math can be a vehicle for students to address important issues in their lives and communities, including social inequities. In response to proposed drafts, close to a thousand math and science professors and STEM professionals signed a letter arguing that this approach would politicize the subject.

Perspectives on math varied by demographics

Some of the YouthTruth findings were encouraging, said Susan May, the director of curriculum at the Charles A. Dana Center, a math research and technical assistance organization at the University of Texas at Austin, who was not involved with the survey. She was “pleasantly surprised” to see that 70 percent of students thought they could be good at math if they worked hard at it.

“We’ve done a lot of work over the past 20 years with growth mindset—Carol Dweck, David Yeager. I thought, huh, maybe some of this is paying off,” May said, referencing the idea that a person’s abilities aren’t fixed, but can be improved through effort.

Perspectives on math varied by demographics and family background, however.

Students whose parents held graduate degrees were significantly more likely than their peers to say that it is important to learn math, that they can be good at math if they work hard, and that they feel comfortable asking questions in class.

Comfort with asking questions was related to other aspects of student identity, too. Boys were more likely than girls to say that they felt that they could ask questions in class. And white students were more likely to say so than Hispanic students—50 percent compared to 40 percent, respectively.

It’s possible that students whose parents have advanced degrees have a window into math’s applications later in life that their peers don’t have, said de Forest.

What might be able to change students’ perspectives on the subject? The researchers examined a specific subset of the data for clues. They looked at students who met all three of the following criteria:

- They strongly agreed they could be good at math if they worked hard;

- They said they always kept trying in math when the work gets hard; and

- They said they always felt comfortable asking questions.

In their open-ended responses to the survey, these students surfaced a similar theme: Their teachers created classrooms where they felt challenged, but also cared for, and encouraged to ask questions.

Teacher-student relationships are a critical piece of this puzzle, de Forest said. “Math is a social environment,” she added. It’s “low-hanging fruit” to create a space where students feel safe to explore and discuss, she said.

Students think ‘school math’ is uninteresting

Despite the variance in how students perceived their own math identities, they agreed on one thing. The problems they worked on in math class weren’t that interesting.

Less than half of students said that their work was often or always interesting, with 23 percent saying it never or rarely was. These findings were similar across demographics—gender, race, the year in which the student took Algebra I, and parent education level.

Researchers held more open-ended discussions about this finding in focus groups with students in two districts. In these conversations, the high schoolers drew a distinction between “school math” and “real math.”

School math, they said, were the subjects needed to graduate and stand out in the college admissions process. But real math would help them navigate the financial landscape they would encounter as adults. Students offered examples of these skills, which they wanted to learn in class—managing a bank account, investing, understanding loans, and filing their taxes.

“That’s really a proxy for wanting to understand power and how government works,” said de Forest. “There’s a connection between this desire for math literacy and a desire for citizenship.”

Financial literacy is important, said May, but the answer to the engagement question isn’t to make the high school math curriculum all about taxes. “It’s not all of what the power of math is,” she said. “I think that’s where we have failed to portray to students the value around modeling problems, modeling phenomena in the world, making predictions, statistical analysis.”

Some states, including Ohio, Oregon, and Utah, have tried to better align math course pathways to students’ college and career goals. Twenty-two states have signed onto the Launch Years Initiative through the Dana Center, which aims to create broader options for advanced math in high school and modernize math courses and content.

Still, there can be a tension for teachers between spending time on real-world, rich problems and preparing their students with the knowledge they need to graduate.

“What I often see in the implementation side is this corner that teachers find themselves in, which is preparing for a state accountability test, which is often very skills-driven, versus taking time to do interesting problems, and feeling kind of trapped,” May said.

In her role at the Dana Center, May works to develop middle and high school curricula that try to bridge that gap.

Figuring out how to strike this balance is crucial, said de Forest.

“The curriculum needs to be taught in a way that’s contextualized for students, so that they can see the pathway into college or career or a trade,” she said. “They deserve the answer to that.”