How do math teachers select curriculum materials, and what instructional practices do they use? A new EdWeek Research Center survey sheds some light on these questions.

Earlier this month, Education Week published a series of articles on elementary math instruction. Those stories were informed by results from a nationally representative survey of about 300 math teachers, across grade levels in K-12.

Questions about what constitutes effective math instruction are once again in the spotlight. A debate in California over the state’s proposed math framework has garnered national attention as it’s touched on perennial debates in math education: tracking, conceptual vs. procedural learning, and how much teachers should work to make math relevant to students’ lives.

At the same time, recent results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress demonstrated that students’ math achievement plummeted during the pandemic, underscoring the importance of identifying practices that will help students succeed in the subject.

We’ve compiled a few other results from the survey here with new insights on curricula and how teachers structure their lessons.

Read on for more on how math teachers use—or adapt—district-provided curricula, where they source supplemental materials, and how they ask their students to approach problem-solving.

Most math teachers use curricula and materials from multiple sources

The majority of the teachers in this survey said they used a core math curriculum. But just over half said that they don’t follow it to the letter, picking and choosing different parts. About 1 in 5 teachers said they don’t use any core program at all.

The most common source of math materials was the internet, or lesson sharing websites. Games, apps, and materials that teachers bought or created on their own were also popular.

District-provided curriculum trailed all of these sources—only 46 percent of teachers said they regularly use core materials provided by their school system to teach their math classes.

These results are in line with other surveys of math teachers in recent years.

The RAND Corporation collects data on how teachers select and use materials in its American Instructional Resources Survey. Results for the 2021-22 school year show that about 20 percent of teachers didn’t use resources provided by their district.

When teachers didn’t use these district-provided materials, it was for a host of different reasons, RAND found: some teachers said the curricula didn’t meet students’ needs, others that they didn’t have time to learn how to use these resources, or that they were difficult to use.

There’s another concern with finding the right materials, said Tiffany Miera, a 5th grade math and science teacher at Needham Elementary School in Durango, Colo. (Miera was not involved in the survey.)

“It needs to have the balance of skills work, and being able to get those skills that are necessary for each grade level’s standards, but also that problem solving piece that connects to real world math and real world situations,” she said.

In Miera’s experience, most math curricula lean in one direction or the other—skills-heavy, or more oriented toward problem-solving—and teachers have to make up for the gaps.

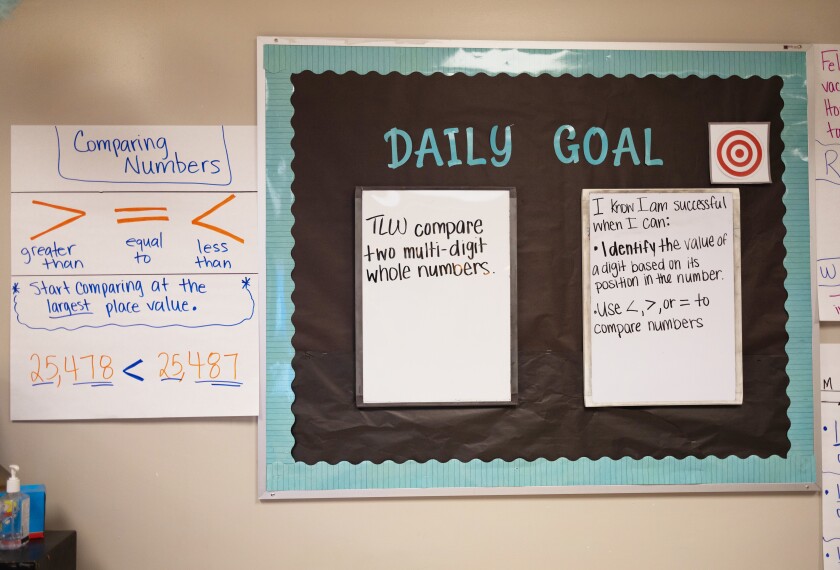

Teachers regularly try to engage students in ‘productive struggle’ and problem-solving

Most teachers in Education Week’s survey said that they try to integrate the teaching of skills and problem-solving.

Research supports the idea that attaining fluency with math procedures and developing conceptual understanding of math concepts is an iterative process—the two types of knowledge build upon each other.

Most teachers also said they’re engaging students in problem-solving daily, and asking students to explain how they arrived at their solutions.

The survey also asked teachers about “productive struggle”—the idea that students are asked to grapple with complex ideas and novel situations as part of the problem-solving process, rather than the sole goal being the correct answer.

It’s a popular approach in math education, with the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics including it in their guiding documents. Even so, some math researchers have criticized the idea, arguing that struggling with complicated tasks without enough guidance can leave students frustrated and lead them to develop misunderstandings about how certain processes work.

Embracing productive struggle is a district priority in Miera’s school system, she said. “It’s in there daily, for them to have some sort of challenge.”

Most teachers in the EdWeek Research Center survey said their students engaged in productive struggle at least weekly, with a quarter saying it occurred daily.

Students should be challenged to think through problems in a way that deepens their understanding, a process that should feel “somewhat effortful,” said Jodi Davenport, a senior managing director at WestEd, whose work focuses on applied cognitive science in math instruction.

But exactly how much students should struggle, and what makes struggle productive vs. unproductive, is harder to pin down. “Does that have a similar meaning for everybody?” she asked.

There isn’t a “ready-made metric” to define how much struggle is enough, said Percival Matthews, an associate professor of educational psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “I don’t think it’s a particularly simple thing,” he said.

Then, there’s the question of how much scaffolding students need to access a complex problem in the first place. Some teachers may want to be more hands-off, Matthews said, because asking students a lot of prompting questions can feel like interrupting their problem-solving process.

But in some cases, asking a simple question can help redirect students and avoid struggle that’s unproductive, Matthews said. For instance: Do you know what the problem is asking you to solve for?

“Where are you going to go if you have no idea what the question is even asking you?” he asked. “There’s probably some balance that needs to happen to make sure that certain ways of self-monitoring are happening.”

Data analysis for this article was provided by the EdWeek Research Center. Learn more about the center’s work.