In the late 1980s, the Biosphere 2 project sealed a team of scientists inside a self-sustaining miniature world. Their goal was to see if a closed system could support human life, serving as a potential blueprint for survival on Mars. A surprising phenomenon emerged: Once the trees inside the dome grew to a certain height, they simply toppled over. Scientists discovered the trees lacked “stress wood,” a crucial feature that develops only when a tree is exposed to the resistance of wind.

This same principle applies to education: If students never meet resistance from mistakes, they fail to develop the resilience necessary to achieve great growth. Mistakes are the “wind” that helps them grow strong in mathematical thinking and prepares them to stand in the face of the complex problems of the real world.

Across the United States, math scores are slipping, and anxiety about math is negatively affecting students as early as elementary school. I’ve watched students hesitate, doubt themselves, and disengage from a subject all over a mere mistake.

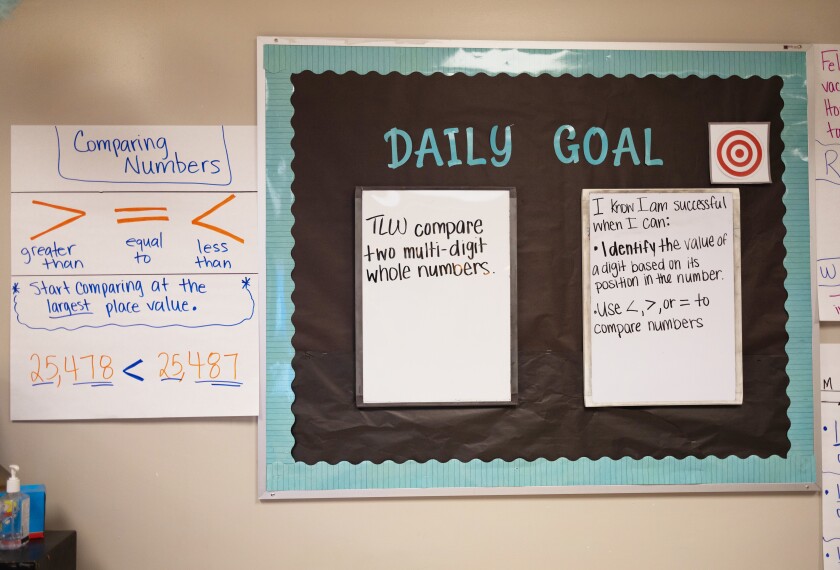

This mistake-celebrating approach we need instead begins with a shift in mindset. Too often, students believe that success in math is about being “naturally good” at it, which makes mistakes feel like evidence they don’t belong. A growth mindset flips that narrative, reframing mistakes as an essential part of learning. When teachers create a classroom culture that normalizes error-making and encourages students to analyze, discuss, and understand their missteps, mistakes can be powerful tools for learning.

The advantage occurs when teachers are not just telling students mistakes are valuable but structuring learning so errors become productive. Here are several strategies I’ve used as a classroom teacher, instructional coach, and student-teacher adviser that can reshape how math is taught and experienced.

1. Have a ‘favorite no’

One of my favorite practices is called My Favorite No. In this routine, students solve a problem (ideally anonymously) on index cards, which the teacher collects and publicly sorts by right and wrong answers (“yes” and “no”). The teacher then selects a “favorite no”—a wrong answer that illustrates a common error or a frequent misconception—and uses it as the starting point for discussion. Students are intrigued: Whose “no” card will be chosen? Will they have made the same mistake? Students see that errors are not shameful but a normal part of learning. Teachers can say things like: “Let’s look at this answer—what can we learn from it?” or “Why do you think this mistake happened, and how can we fix it?” This approach transforms mistakes into illustrations and helps students understand processes, not just answers.

2. Identify and label types of mistakes

I encourage teachers to classify mistakes to help students understand what went wrong. A smart mistake occurs when a student follows a rule correctly, but an exception exists. A speed error happens when a student rushes and overlooks a step. A completion error arises when directions are misunderstood or only partially followed. Finally, an out-of-alignment mistake may occur when numbers or steps are spatially misaligned, leading to a wrong answer despite correct thinking. Teachers can guide students by saying: “This is a smart mistake—we followed the rule correctly, but there’s an exception here,” or “Looks like a speed error—you rushed and skipped a step. Let’s go back and check.”

Students can be encouraged to recognize when their errors fall into patterns (“Gee, I keep making the same kind of mistake!”) and can course-correct accordingly (slowing down, lining up the decimal point, etc.) rather than tragically labeling themselves as “bad at math.” Naming errors normalizes them, removing the stigma and turning mistakes into learning moments.

3. Anchor quizzes in correction

Traditional quizzes can penalize students for mistakes without giving them a real chance to learn from them, even when a teacher offers “recovery points” to students who correct problems they missed. I recommend giving students quizzes that are already fully solved, though solved incorrectly with intentional errors to find and fix. Everyone begins by analyzing the problem with a critical lens that asks students to affirm or challenge the work in front of them. This shift transforms assessments away from penalizing and instead promotes understanding and boosts confidence.

4. Practice with provided answers

Consider assigning problems where the correct answer is provided upfront and have students show the steps that lead there. The emphasis is on showing the work, not simply reproducing the answer. (Not to mention, many texts provide answers at the back of the book.) This practice strengthens procedural understanding, discourages shortcuts, and builds the habit of verifying one’s reasoning at every step.

5. Adopt the language of ‘still learning’

Classroom culture is shaped by the language we use. I remind students and myself that we are all still learning. When mistakes occur or a student says “I don’t know,” I say, “We’re still learning how to solve these.” This phrasing frames errors as part of an ongoing journey, not a final judgment. Teachers who model their own mistakes, especially in subjects like math where they may have struggled personally, demonstrate that even experts grow through trial and error.

6. Encourage ongoing answers

Picture the classroom where a teacher asks, “What did you get?” In traditional classrooms, once the right answer is given, discussion often stops. I advocate ongoing answers: Continue asking for contributions even after someone gets it “right.” Ask, “Are there other answers?” or “Did anyone get anything else?” Encourage students with prompts like: “Great, that’s one way—who has another way to solve this?” or, when appropriate, “Let’s hear some more ideas; there isn’t only one right answer.” This approach honors diverse thinking and allows students to explore multiple solution paths, rather than reinforcing a single “correct” approach.

In my decades of teaching and leadership, I have learned that the strongest mathematical minds are not those who never err; they’re the ones who learn deliberately from mistakes and persist through challenges. By celebrating and spotlighting errors rather than fearing or hiding them, we equip students to develop confidence, curiosity, and lifelong resilience in math, and maybe life. In the end, embracing mistakes may be one of the most powerful—and most joyful—ways to help students reach their highest potential.