Fewer than 1 in 4 high school seniors and a little more than a third of 4th and 8th graders performed proficiently in science in 2019, according to national test results out this week.

The results are the latest from the National Assessment of Educational Progress in science. Since the assessment, known as “the nation’s report card,” was last given in science in 2015, 4th graders’ performance has declined overall, while average scores have been flat for students in grades 8 and 12.

“The 4th grade scores were concerning,” said Peggy Carr, the associate commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, which administers NAEP. “Whether we’re looking at the average scores or the performance by percentiles, it is clear that many students were struggling with science.”

The percentage of 4th graders performing below the basic achievement level in science rose significantly in the last decade, to 27 percent, while the percentage at or above the “proficient” level fell in the same time, to 36 percent. (The proportions for grades 8 and 12 remained flat; a third of 8th graders were “below basic,” and slightly more were at or above proficient, while nearly twice as many 12th graders fell below basic as met the proficient benchmark, 41 percent to 22 percent, respectively.)

To put that in context, only a little more than a third of 4th graders could consistently explain concepts such as how forces change motion, how environmental changes can affect the growth and survival of animals or plants, and how temperature affects the state of matter.

And more than 40 percent of high school seniors could not consistently describe and explain things like the structure of atoms and molecules or design and critique scientific experiments and observational studies.

Nearly 90,000 students in grades 4, 8, and 12 from more than 3,900 schools participated in the 2019 assessment, the first digitally based administration of the science test. It included both interactive simulations in which students worked through scientific investigations by computer and hybrid hands-on tasks using kits provided by NCES. The problems were individual, though an international assessment in 2017 suggested that U.S. teenagers outperformed their global counterparts in math and science problems that require collaborative problem-solving.

Carr said the test generally aligned with the Next Generation Science Standards, on which 40 states and the District of Columbia have based their own science teaching standards. Georgia, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire are developing new science assessments under a federal pilot program.

Yet in grades 4 and 8, scores declined from 2015 for lower-performing students in all three science content areas: physical, life, and earth and space science. In grade 12, physical and life science scores fell while earth and space scores were flat since 2015.—

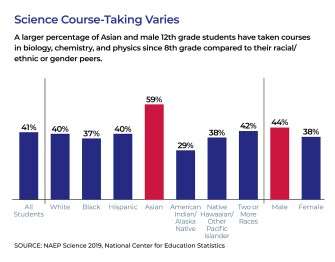

An analysis of NAEP’s background data finds only about 40 percent of 12th graders had even taken all the core science subjects of biology, chemistry, and physics during high school. However, there were large differences in coursetaking by racial groups, with Asian-American students more than 20 percentage points more likely to take all three core science classes by 12th grade than students of any other racial group.

Trends mirror those in reading, math

Across grades 4 and 8, the scores of the lowest-performing 10 percent of students fell since 2015, while the top performers held steady. In 12th grade, low- and high-performers alike were flat from 2015.

These widening gaps between the highest- and lowest-performing students, particularly in grade 4, mirror similar trends seen in national and global reading, math, and social studies assessments.

Lynn Woodworth, the commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, which administers NAEP, said the center is studying ways that poor reading skills among the lowest-performing 10 percent of students might account for some of the gaps across multiple subjects.

There were no differences in performance between boys and girls in grades 4 and 8, though boys outperformed girls at grade 12. Compared with 2015, the scores of Black and white 4th graders declined while those of other racial backgrounds stayed flat. There were no changes by racial group from 2015 at higher grades.

“Particularly the 4th grade results, seeing the decline over the decade from 2009 is just very disappointing,” said Erika Shugart, the executive director of the National Science Teaching Association.

Teacher collaboration can bolster science instructional time

From surveys with teachers that accompanied the assessment, NCES researchers found students have less time to learn science than they have had in the past. Fifty-five percent of 4th graders got less than three hours of science instruction per week in 2019, an increase of 2 percentage points in the number of 4th graders getting less instructional time since 2015. By contrast, about 68 percent of 8th graders got at least four hours of science class per week, the same as in 2015.

Moreover, half of 12th graders, 42 percent of those in grade 8, and 30 percent of 4th graders only engage in “scientific inquiry-related classroom activities” once or twice a year—or never.

“The majority of 4th graders are spending under four hours a week in science, and NSTA strongly recommends that science be a minimum of an hour a day, five hours a week,” Shugart said. NAEP analysis found 4th graders who had less than three hours of science each week scored significantly lower than those who had the recommended five hours or more. “We understand the competition with math and English/language arts is fierce, and science right now is losing out. We think it’s really important that we help education stakeholders and parents understand how important science education is at all levels but especially at those elementary school levels. We’re not going to see a shift in scores until we’re spending more time in inquiry-based science.”

Some districts are trying to make room for science throughout the curriculum. In rural Palmyra, Pa., for example, Palmyra Middle School teachers across all subject areas collaborate for the school’s annual environmental education camp.

“We literally pack up all of 7th grade and live at the base of the Appalachian Trail for two weeks, doing full-on science with all hands on deck: The English teachers are teaching science, the math teachers are teaching science and environment,” said Jeff Remington, a science, technology, engineering, and math teacher at Palmyra Middle. After the pandemic closures prevented the camp from taking place last year, and budget cuts seemed likely to do the same this spring, the community raised money to pay for teachers to send more than 600 students from both grades 7 and 8 this year. “We are doing a double dose of camp this year to make up for lost time from COVID. These kids have been, like, glued to devices just because of school and everything else, so this is the first time they’ve been kids since the pandemic started.”

Yet even before the pandemic, Remington said he had seen instructional time for science decrease, particularly in lower grades, in the years since the subject was dropped from requirements for federal accountability testing.

“Elementary science, I think, across the state and across the country, is what has really been hurting in science, because of the focus on high-stakes testing for math and language arts,” he said.

“I’d say we’re doing pretty well [in secondary science] because we chose to do hands-on inquiry for the lessons that we are doing, but at the elementary level, our district’s emphasis is still highly, highly on math and language arts,” he said. “When they get to middle school and we get to do these experiences, I think we can make up for some lost time from the elementary.”