When elementary school students in her district struggle in math, Elizabeth Abel wants to get them support as soon as possible.

That’s because addressing students’ gaps in kindergarten, 1st, and 2nd grades makes it much more likely that they will be successful in upper-elementary grades, said Abel, a district elementary math coach in Hernando County schools in Brooksville, Fla.

So she was glad when Florida lawmakers passed a measure last year mandating that schools do just that—evaluate students for early difficulties, and intervene.

“That’s something that we in the math community were really excited to see,” said Abel. “Now people have to make a concerted effort to make sure that they are fitting those minutes in.”

Florida is one of seven states that have recently passed laws requiring schools to screen students for early math difficulties—giving short assessments that evaluate whether a student is performing at grade level. While these screeners are commonplace in early reading instruction, fewer districts have similar systems set up in math to find and support students who need extra help. (For more on why, see this story.)

But working with these students to improve their number sense—their basic understanding of quantity, magnitude, and arithmetic—can pay big dividends, said Nancy Jordan, a professor of learning sciences at the University of Delaware. These abilities lay a foundation for higher order math skills that students learn in upper elementary and middle school.

Earlier in her career when she’d just started studying math screening, Jordan recalled a principal telling her that students in the school didn’t start struggling in the subject until 3rd grade. “People just thought that it wasn’t important early on, or that the difficulties can’t be identified early,” Jordan said. “But in fact they can.”

Math screeners come in multiple forms that serve distinct purposes, and they evaluate different skills at different grade levels. Experts also caution that screening should only be the first step in planning intervention. Read on for three things to know about these short tests.

1. Different screeners assess different math skills

For the most part, screening systems in math assess students several times a year—once in fall, winter, and spring, said Ben Clarke, a professor of school psychology at the University of Oregon, who studies math assessment and instruction.

The tests range in length, with the shortest taking only a few minutes, and the longest lasting up to an hour.

The National Center on Intensive Intervention, a program of the American Institutes for Research, publishes evaluations of different screening measures in math. The ratings show how well tools correctly identify students who are at risk, whether there’s evidence that the tools are reliable and valid, and various usability features.

Most screeners for young children test their ability to understand quantities and manipulate numbers. But within those broad goals are a number of discrete skills.

The most commonly assessed are counting, identifying the Arabic numerals that represent numbers, being able to discriminate between larger and smaller quantities, and determining missing numbers within a set, according to a 2022 review of studies on screening measures published in the Journal of School Psychology.

Children who struggle with these tasks can make gains with interventions, said Jordan. But foundational math skills aren’t always bounded in the same way that early reading skills are, she said.

In reading, once students learn how to map spoken sounds to written letters, they can move on from practicing phonics. But some math skills are more open-ended, and can’t be fully mastered in that same way, said Jordan.

For example, a task such as determining the missing number in a set can get harder if the set is bigger. Some tasks become more difficult when students move from working with concrete representations—such as counters or blocks—to symbolic representations, like written numbers.

“With math, a lot of it is so conceptual,” Jordan said. “There are some children that will need a lot of intensive support throughout their schooling.”

2. Older kids may need different supports

As students move through the grades, screening measures evaluate more—and more complex—skills.

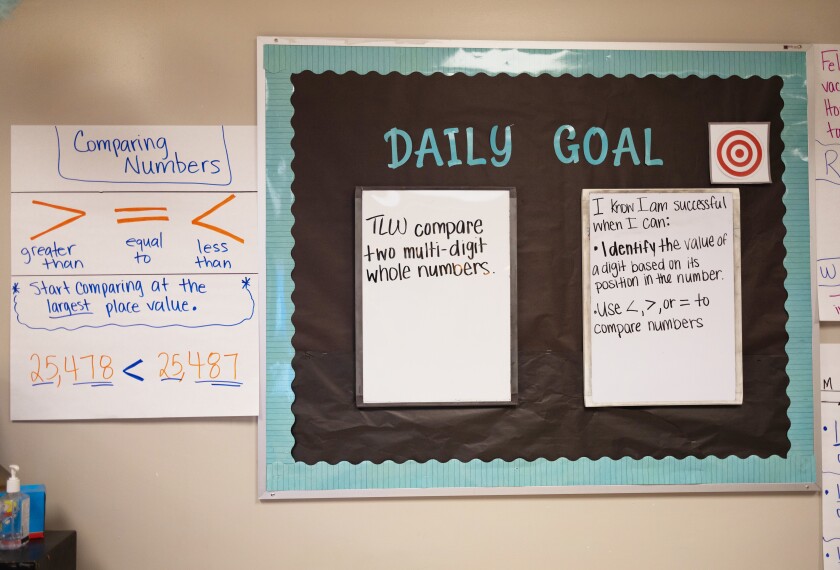

In 2nd through 5th grade, students still need to know basic computation, said Carrie DeNote, the past president of the Florida Council of Teachers of Mathematics. But they also need to be able to apply those skills in different capacities, such as in solving increasingly complex word problems.

There are also gateway skills that predict students’ ability to succeed in higher level math, said Jordan, such as fluency with fractions.

“Given the multifaceted nature of mathematics, identifying one or two measures that represent mathematics proficiency broadly over multiple grade levels seems elusive,” the authors of the 2022 Journal of School Psychology paper write. In other words, there’s not one universal indicator that can flag potential problems.

And older students can still struggle with foundational concepts.

Laura Jackson, a consultant and coach who works with parents of dyscalculic children and teachers who support these students in the classroom, said that she works with many children are in late elementary or early middle school. Dyscalculia is a learning disability that affects individuals’ ability with math and number-based learning.

These students don’t have basic number sense, and the hands-on interventions designed to build that skill can feel infantilizing for preteens, like preschool math, she said.

“Meanwhile they’re in 7th grade math, 8th grade algebra, and it’s really a struggle for them,” she said. For Jackson, the emotional roadblock that older students can experience reinforces the need for schools to catch and address problems early.

3. Screening students should be part of a ‘coherent instructional program’

Screeners can tell teachers that students aren’t performing at grade level, but they don’t usually show why, said Mary Pittman, the director of mathematics for TNTP, an organization that consults with schools on teacher training and instructional strategy.

It’s important for schools to break that information down further, she said, looking at sub-scores on different skills and using those to plan for intervention.

“Screening has to be a part of a coherent instructional program, where we are screening so that we can support kids in strategic ways to get to grade-level content,” said Bailey Cato Czupryk, the senior vice president for research and impact at TNTP. “The purpose of knowing where they are is so that we can do something.”