In a world drenched in data, we must ensure that students know the meaning of numbers.

Our world is awash in numbers. Headlines report the latest interest-rate cuts by the Federal Reserve, hikes or drops in gasoline prices, trends in student test scores, results of local and national elections, risks of dying from colon cancer, this season’s baseball statistics, and numbers of refugees from the latest ethnic war.

Quantitative thinking abounds, not only in the news but also in the workplace, in education, and in nearly every field of human endeavor. Anyone who wishes can obtain data about the risks of medications, per-student expenditures in local school districts, projections for the federal budget surplus, and an almost endless array of other concerns.

If put to good use, this unprecedented access to numerical information will place more power in the hands of individuals and serve as a stimulus to democratic discourse and civic decisionmaking. Without understanding, however, access to this information can mystify rather than enlighten the public. If individuals lack the ability to think numerically, they cannot participate fully in civic life, thereby bringing into question the very basis of government “of, by, and for the people.”

Considering the deluge of numbers and their importance in so many aspects of life, one would think that schools would focus as much on numeracy as on literacy, on equipping students to deal intelligently with quantitative as well as verbal information.

Yet, despite years of study and life experience in an environment immersed in quantitative data, many educated adults remain functionally innumerate. Businesses lament the lack of technical and quantitative skills among prospective employees, and virtually every college finds that many of its students need remedial help in mathematics. Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress show that the average mathematics performance of 17- year-old students is in the lower half of the “basic” range and well below “proficient.” Moreover, despite slight growth in recent years, average scores of Hispanic students and African-American students are near the bottom of the “basic” range.

If individuals lack the ability to think numerically, they cannot participate fully in civic life.

Common responses to this well-known problem are either to demand more years of high school mathematics or more rigorous standards for graduation. But even individuals who have studied calculus often remain largely ignorant of common abuses of data, and all too often find themselves unable to comprehend (much less to articulate) the nuances of quantitative inferences. As it turns out, it is not calculus but numeracy that is the key to understanding our data-drenched society.

The expectation that ordinary citizens be quantitatively literate is primarily a phenomenon of the late 20th century. Its absence from the schools is a symptom of rapid changes in the quantification of society. As the printing press made literacy a societal imperative, the computer has made numeracy an essential goal of education. Yet practice in our nation’s schools and colleges does not reflect that goal. We need, therefore, to broaden our national conversation about education to include careful attention to numeracy.

This conversation must be carried forward first and foremost in school and college settings. If asked, faculty members and administrators at most schools and colleges today probably would say that they intend to produce quantitatively capable graduates. But the typical response, a more intense focus on a traditional mathematics curriculum, will not necessarily lead to increased competency with quantitative data.

This conclusion follows from the simple recognition that numeracy is not the same as mathematics, nor is it an alternative to mathematics. Today’s students need both mathematics and numeracy. Whereas mathematics asks students to rise above context, quantitative literacy is anchored in real data that reflect engagement with life’s diverse contexts and situations.

In life, numbers are everywhere, and the responsibility for fostering quantitative literacy should be spread broadly across the curriculum.

The case for numeracy in schools is not a call for more mathematics, nor even for more applied (or applicable) mathematics. It is a call for a different and more meaningful pedagogy across the entire curriculum. In life, numbers are everywhere, and the responsibility for fostering quantitative literacy should be spread broadly across the curriculum. Quantitative thought must be regarded as much more than an affair of the mathematics classroom alone.

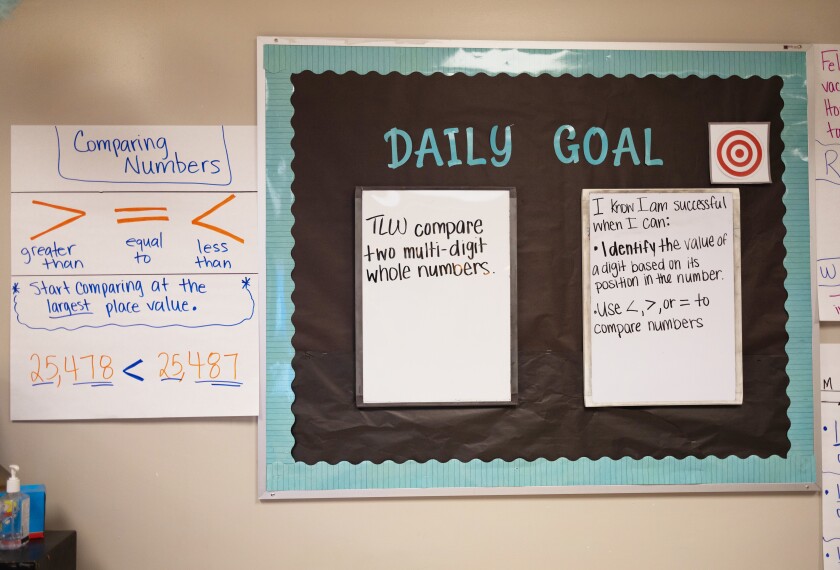

Quantitatively literate citizens need to know more than formulas and equations. They need to understand the meaning of numbers, to see the benefits (and risks) of thinking quantitatively about commonplace issues, and to approach complex problems with confidence in the value of careful reasoning. Quantitative literacy empowers people by giving them tools to think for themselves, to ask intelligent questions of experts, and to confront authority confidently. These are the skills required to thrive in the modern world.

Lynn Arthur Steen is a professor of mathematics at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minn., and led the team of scholars and educators that produced the book Mathematics and Democracy: The Case for Quantitative Literacy. The book was the work of the National Council on Education and the Disciplines, an education reform initiative centered at the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation in Princeton, N.J.