In the first months of the pandemic, school leaders and state officials made a unified call for grace, an acknowledgment that students and teachers both had more pressing concerns than academic expectations: They relaxed grading policies, canceled end-of-year assessments, or directed teachers not to fail students because of work not completed during shutdowns.

Over the past two years, though, school systems have brought back many of these requirements. State and school district leaders’ pleas for lenience have thinned, and their expectations for teachers and students have risen. Teachers are tasked with “catching up” students, trying to prepare them for success in the next grade and beyond while accounting for the disruptions of the past two years.

“The expectation is ‘back to business,’ and that’s why teachers are stressing,” said Marina Martinez, a 7th grade math teacher and the department chair at Bancroft Middle School in San Leandro, Calif.

Teachers say the dynamic puts them in a bind: They want to hold their students to high expectations, giving them the kind of meaty work that has a better chance of re-engaging them in school and preparing them for the next grade and beyond. But they also say that schools aren’t really “back to business” yet, and they don’t want to add more stress to students’ lives during an already difficult time.

“There’s this fine line between ‘we’re still teaching in a pandemic,’ but we want kids to understand that there are certain expectations of their behavior, their responsibilities,” said Nancy Nasr, the science department chair at Granada Hills Charter High School in Los Angeles.

“That’s part of our teaching, especially in the high school. It’s not just the content, it’s developing these responsible citizens who understand the importance of deadlines, doing what you’re supposed to do, following through on that.”

In an EdWeek Research Center survey from December 2021, one in three teachers said that the rigor of their instruction had decreased compared to before the pandemic. More than 80 percent reported that they had increased their focus on reteaching. And about half of all teachers said the amount of homework they assign and the strictness of their grading policies are still more lax than they were pre-pandemic.

Is rigor possible during disrupted learning?

Teachers say that so much time without traditional school routines has shaken students’ confidence in their ability to wrestle with cognitively demanding assignments. About seven in 10 reported that the quantity and quality of work that students turn in has decreased.

In interviews with Education Week, some teachers worried that continuing to relax expectations would lower the quality of education that they were able to provide, and decrease the chances that students would be prepared for the next grade.

But others argued that these changes to their practice didn’t necessarily translate to “easier” classes. Instead, the pandemic has changed the way they conceptualize rigor, they said.

Nasr, for example, has moved from a more traditional, multiple-choice summative test to more holistic end-of-term assessments that account for students having been in and out of the physical classroom at different times throughout the semester. “The hammer coming down, the multiple-choice, punitive grading culture has changed for me,” Nasr said.

There has always been a “tension” between covering all of the content and skills that students are going to be evaluated on, and taking the time to help students’ grow their capacity for deeper learning, said Camille Farrington, a managing director at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, who studies academic rigor.

“Given that the system is really at a breaking point, and there’s wholesale evidence that students can’t live through COVID and keep up at grade level, … what are we going to do about it? I don’t think there’s incompatibility between COVID and rigor, but I think there is incompatibility between COVID and broad grade-level standards.”

Gaps in basic skills hinder acceleration

One solution is the idea of “acceleration.”

If a teacher is working with a 4th grade class that was in remote learning for most of 3rd grade math, for example, she would introduce them to 4th grade concepts while providing “just-in-time” support when they needed to rely on 3rd grade knowledge or skills.

Instead of going back to reteach entire units from the previous grade, teachers and students can keep moving forward, introducing kids to more challenging content. Several national education groups have endorsed this strategy during COVID, when the unpredictable nature of school building shutdowns—and students’ lives—mean that kids may miss different chunks of instruction.

But some teachers say that students’ increased struggles with basic skills make moving forward difficult.

“I think about 8th, 9th grade, and the main focus is equations. And the kids are struggling because they don’t have their basic facts down,” Martinez said.

In years’ past, she wouldn’t let students use calculators, asking them instead to draw on their stored knowledge of math facts. But she’s changed that this year, after seeing that her students are having more trouble with that recall than they have in the past. “It gets to a certain point where we’re so dependent on those basic facts that we’re not pushing the math itself forward,” she said.

Zachary Chan, a 3rd grade reading teacher at the Young Women’s Leadership Academy in San Antonio, said he’s reteaching handwriting and concepts of print—skills that students would normally master by the end of 1st grade.

“We’re focusing more on growth,” Chan said. “I feel pressure to have them grow more than a year in writing instruction in that year they’re with me.”

Some older students are having trouble with reading skills, too, said Lisa Vanderlinden, a chemistry and biology teacher at Kennedy High School in Bloomington, Minn. “Before a lab, I’ll need to tell them every single thing about the lab that we’re doing, because they’re not as good at reading directions,” she said, of her 11th graders. They also need support with the algebra involved in her class, such as balancing equations.

But the bigger problem, Vanderlinden said, is that students are having trouble concentrating and thinking through problems. They’re not as confident in their knowledge.

“I don’t think that they got behind as much on content as they got behind on critical thinking skills and the ability to process challenging information,” Vanderlinden said.

This dip in students’ ability to take on cognitively demanding work is a much bigger hurdle than some gaps in their understanding of math formulas, she said.

The pandemic has heightened this kind of response from students, teachers say, but the phenomenon isn’t entirely new.

Martinez said that she and her colleagues have always provided students with scaffolds that help them access grade-level work, breaking down a problem into its component skills and walking students through step by step. It’s a strategy that would ideally let kids wrestle with concepts and ideas that are more challenging, but sometimes it doesn’t work out that way.

If teachers are cutting up a concept or question into too many chunks, they can hinder students’ ability to make connections themselves and see the “big picture,” she said. Now, that problem has gotten worse.

How should schools measure rigor?

Schools have not historically developed students’ capacities to take on rigorous work without over-scaffolding, said Zaretta Hammond, a teacher educator and the author of Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students.

This has especially affected Black and brown children, who are more likely than white children to be given work that’s watered down and not cognitively challenging, she said. And the pandemic revealed how deeply inequitable this problem is—how the education system has failed to cultivate historically marginalized students’ capacity to carry the cognitive load and process new content, so that they can turn it into usable knowledge, Hammond said.

A lot of students disengaged from school during remote learning because they found virtual learning uninteresting and lacking in any intellectual curiosity or joy, she said. But others, she added, disengaged because they weren’t prepared for learning without teachers’ over-scaffolding.

Now, students might be reluctant to engage because they don’t see a purpose in the general directive to push forward—or a way to do so, Hammond said. They want a clearer message about why they’re learning what they’re learning, and they need the time and support to build the strategies that will allow them to process complex tasks by themselves.

“If I can’t swim, putting you at one end of the river and saying, ‘The only way to get across to freedom is to swim,’ you’re stuck,” she said.

This is why academic acceleration doesn’t mean going faster, Hammond said. Students need time to learn how to swim: to build the cognitive structures and routines that enable them to take on rigorous work. She likened it to how even professional musicians continue to drill their scales, maintaining a solid foundation that allows them to play complex pieces.

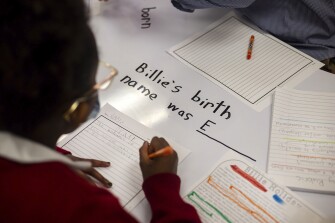

This year, some teachers have tried new ways of helping students develop those routines. In her 7th grade math class, Martinez has started to ask her students to keep a notebook. There, students can write down or draw out their own reminders. She’s helping her students solidify their own strategies to “review, reinforce, and remind,” she said.

Other teachers are looking for new ways to spark students’ intellectual curiosity, something that Farrington, from the University of Chicago, says is a key entry point to rigorous work.

“I’m moving more toward, ‘How can we use science, or how can we do science, to better our society?’” Nasr said. She’s developed lessons around the Flint, Mich., water crisis and air pollution issues in Los Angeles that offer applications for the core ideas of her chemistry class, but also pique students’ curiosity. They’re driven to answer the question: How could science solve these problems?

But individual educators’ attempts to help students develop new ways of thinking and hook their interest can only go so far without time and guidance from administrators. Asking individual teachers to shoulder this transformation to more cognitively demanding work isn’t sustainable, Hammond said. Making time for rigor requires shifts in school and districtwide priorities, she said.

Chan, the Texas 3rd grade teacher, wishes that state or federal leaders, too, could offer more guidance about how to approach student needs right now.

“The intensity of everything has gone up,” he said, as education leaders call on teachers to raise the rigor and play catch-up. But he also feels—and keeps hearing the message—that he should still be showing empathy. It’s not clear to him how to do both.

“It’s been a balancing act for everybody,” Chan said. “And I think a lot of the load has been placed on teachers.”