With President Trump prepared to issue an executive order calling for the closure of the U.S. Department of Education, it’s up to us to figure out what the administration really has in mind for public education, given what we still don’t know. There are a few clues, however, in an email that Education Secretary Linda McMahon sent to her staff just hours after her confirmation on March 4.

In the email, she frames her “final mission” to “send education back to the states.”

Let me be the first to say: Mission accomplished.

Public education is already run by states and local school districts. They provide up to almost 90 percent of the funding for public schools; set the learning standards; choose curriculum; hire and train the teachers, principals and administrators; mete out discipline; and establish graduation requirements.

The feds, on the other hand, provide some extra money for low-income students, students with disabilities, rural students, students learning English, and people attending college. The feds also investigate civil rights violations—a response to the long and troubled legacy of “local control,” like segregation. Through other federal agencies, Washington also pays for preschool for low-income kids and lunch for the 30 million kids who might show up to school hungry.

Federal law still mandates some kind of testing so we can track progress in core subjects like reading and math, but, at this point, there are no real consequences for falling short. And, now that they have gutted the Institute of Education Sciences, which funds education research, we can look forward to knowing even less about the state of learning in America.

Welcome to President Trump’s “golden age” of ignorance.

The new education secretary also promises to empower “all parents to choose an excellent education for their children.” This, of course, has been the promise for generations. An excellent education is still far from true, though blaming education failure on the feds is kind of like blaming climate change on the EPA.

McMahon’s email and the administration’s agenda raise one fundamental question: Is education a matter of national interest? If so, how is the national interest served by shrinking the federal role? That, in turn, prompts another very legitimate question: Has Washington’s involvement in education helped in any meaningful way?

To answer that question, we should not take the word of politicians with little experience in public schools. Instead, we should talk to parents, teachers, and students. Start with the parents of children with disabilities. Talk to school leaders who rely on federal funds to shrink the gap between rich and poor schools. Talk to the millions of people who used Pell grants to earn a college degree. Talk to researchers who use federal funds to study the field and charter school leaders who use federal funds to innovate. Talk to the victims of discrimination who’ve received a small measure of justice thanks to the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights.

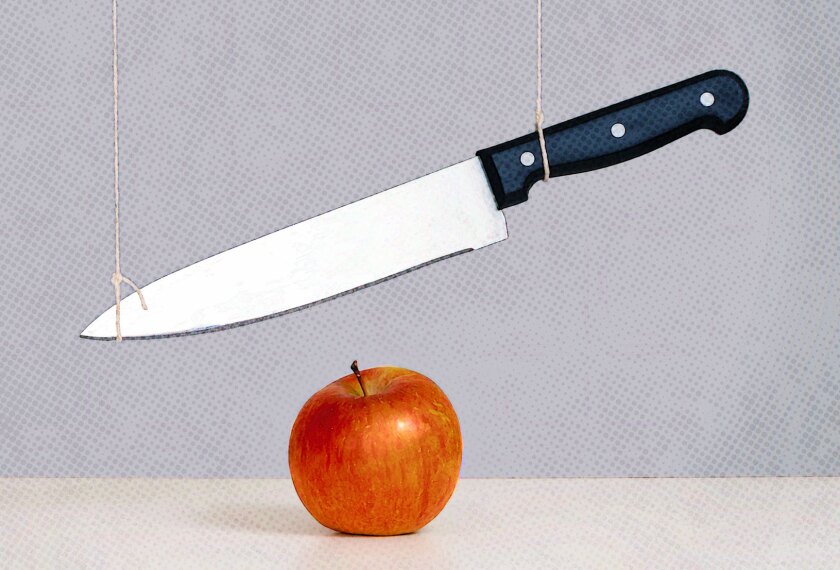

If Secretary McMahon is promising to eliminate the department but keep all of these federal programs in place with block grants, then she really isn’t “sending” education back to the states. She is still holding a sword over the heads of educators if they resist Trump’s agenda, based on the speed with which the department has launched new investigations into schools accused of not following Trump’s executive orders. On the other hand, she will create a bureaucratic mess with multiple federal agencies engaging with schools, instead of just a few—the antithesis of government efficiency.

Sadly, McMahon trades in the same weaponized lies as Trump, lamenting “political ideologies, special interests, and unjust discrimination.” She has complained about “critical race theory, DEI, [and] gender ideology.” She promises to restore “patriotic” education—a euphemism for teaching topics, like slavery, from “both sides.”

Talk to school leaders who rely on federal funds to shrink the gap between rich and poor schools.

It’s also hypocritical to promise “school choice for every child.” If she is determined to eliminate the federal role, why make any federal promises? And, by the way, not everyone wants school choice as defined by this administration. In red states and among Republicans, support for vouchers is soft—especially in rural communities with few private schools. Both Nebraska and Kentucky rejected voucher referenda in November, as did Colorado.

In an especially ironic passage, given that her boss started a for-profit college that the conservative National Review called a “massive scam” several years ago, McMahon decries “millions of young Americans … saddled with college debt for a degree that has not provided a meaningful return on their investment.” On this point, I don’t disagree with Secretary McMahon, but she now works for a president who does. Eliminating the Education Department opens the door for more scams.

After spending the bulk of her nearly 900-word email explaining how the department has effectively been a “trillion” dollar failure, she closes with a warm and inspiring appeal to the civil servants to “join” her in eliminating their jobs. “When our final mission is complete,” she says, “we will all be able to say that we left American education freer, stronger, and with more hope for the future.”

This is kind of like the invitation President Trump extended to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House on Feb. 28, when he suggested surrendering to Russia. Zelensky declined. I suspect many of Secretary McMahon’s 4,200 employees at the U.S. Department of Education will do the same.