|

How do you help students resist the lure—and lucre—of Glitter Gulch and get their diplomas? Las Vegas High School found a way. |

In this land of symphonic water shows and beaming neon, where an Egyptian pyramid offers craps and Elvis performs weddings, an unlikely collection of locals is staging one of the wildest shows in town.

It kicks off shortly after sunup, when not a showgirl stirs, and the luckless are still sleeping off last night’s losses. Miles from the glitter of the Strip, but close enough to feel its pull, a program at Las Vegas High School is encouraging students to weather their surreal surroundings and stick around through graduation, while preparing them for life after it.

Thinking beyond the here-and-now is a tough sell in this city, for high rollers and high schoolers alike.

Stay in school? A restaurant hostess here can pull in $200 a night. Pick up a diploma? Parking cars can earn you 60 grand a year. Thinking about a long-term career? Not likely, when some dropouts can make more than their teachers, easy.

In this ever-changing, multiethnic school, located in the sixth-biggest school district in the country, students are asked to forget all that Vegas math, at least for a while. Each year, about 140 of Las Vegas High’s juniors and seniors commit to a school-to-work program called Partnership at Las Vegas, which tries to improve their job skills and prepare them for college, if they choose that route.

Known around the hallways as PAL, the school-within-a-school allows its students to spend one day a week outside of class, in unpaid internships arranged by the program. The rest of the week, they stick to a standard schedule of courses, while living by the rules of an office. Professionalism and punctuality are mandatory.

It is not always easy. Reminders of a different road, lined with fives, tens, and twenties, are everywhere.

|

Las Vegas students can see the temptations of the Strip from their school. Seeing a better future is more difficult. |

“Money just flows through this town,” says Kirk Wallace, a history teacher in the program, who has seen the city’s effect on students. “They see it. They want a part of it. Kids here don’t see if they don’t finish high school, it will hurt them.”

They are the sons and daughters of pit bosses, blackjack dealers, and waitresses, working- and middle-class folk who came to this sprawling desert metropolis seeking a bigger paycheck and a better life. But at some point, many of those young people decided that a future spent in Las Vegas’ gleaming hotels and casinos, however lucrative, was not enough.

For officials at Las Vegas High School, launching the Partnership at Las Vegas program seven years ago yielded another, partly unexpected benefit: It helped keep kids interested in school. Earlier this year, the federal General Accounting Office, Congress’ investigative arm, identified PAL as one of the nation’s most successful dropout-prevention programs. (This, even though many students say they never considered dropping out.) About 97 percent of PAL’s students graduate, school records show. By contrast, a survey taken over the same period by PAL officials indicated that fewer than 87 percent of the rest of Las Vegas High’s students completed school.

Nevada, unfortunately, is all too fitting a laboratory. The state consistently falls near the bottom in national rankings of dropout prevention, though estimates vary greatly because of different methods of counting. Clark County’s 244,000- student school district, like the rest of the state, is coping with breakneck growth and the needs of a rising Latino population, pupils who face greater economic, cultural, and language barriers to staying in school, local and national education officials say.

At Las Vegas High, those social and demographic forces emerge at every grade level. Some students quit to support needy families who have just moved up from Mexico, others because they have children of their own. Teachers here also point to the city’s transient culture. Families come and go, students who skip between schools can’t keep up, and, eventually, some drop out.

And then there’s the oldest enticement of them all.

“It was so easy to give a smile and get a tip,” recalls Irina Dan, 17, who used to get handed $200 some nights, working as a hostess at the Monte Carlo Resort & Casino after school. After a year, she gave it up. She graduated from Las Vegas High in June.

“For a 17-year-old,” she says, “that’s a lot of money. ... [But] I felt like it was kind of a dead end. I couldn’t take it anymore.”

Still, the promise of fast cash is too much for many students to resist. The Partnership at Las Vegas is trying to help them.

The school’s setting, like much of this city that millions of visitors never see, is equal parts western boomtown and Middle America. Roll east from the valet-laden entrances of the Bellagio and the Tropicana, past cinematic billboards and sidewalks two-deep with tourists, and a new landscape emerges, of sub shops and shoe stores, mortgage offices and mid-priced subdivisions. As the city starts to fade, and sand seems ready to swallow sidewalk, the bulky brick mass of Las Vegas High rises along the side of the road, flanked by palms in the front and a steep brown ridge called Sunrise Mountain in the back.

‘Money just flows through this town.’

Back when it was founded in 1905, the school was nothing but a two-room tent planted in the sandy soil downtown. According to local lore, students were forced to make do with those windswept surroundings for more than a year because the city’s forefathers decided a new jail had to be built first. Folks were calling Vegas the City of Destiny back then, and so it must have seemed to miners, farmers, and railroad workers bringing their children from nearby towns like Searchlight and Goodsprings.

Over the decades to come, Las Vegas High grew like the city around it, so much that in 1993 it moved to a patch of one-time scrubland on the east end of town, where it now sits. Today, a visitor can pass through the outdoor hallways of this 3,100-student school, climb its stairs, gaze out from the second-floor balcony, and behold a desert metropolis no settler could have imagined: The Stratosphere tower and high-rise hotels shimmer through the bright sun and haze, and Kahlúa-colored mountains loom beyond.

“To change, and change for the better, are two different things,” a student’s voice declares over the intercom, as teens shuffle into first-period classes, trading jokes and shouts in English and Spanish.

That message and its implicit warning were obvious to a group of the school’s teachers in the mid-1990s, when they first started talking about starting a program that would prepare students for work and raise their interest in school. Other schools in different parts of the country had tried similar models. Why not at Las Vegas High?

So the teachers went knocking on their principal’s door, harboring fresh hopes tempered by lingering memories of rejections by other administrators, at other schools. As it turned out, they had little reason to worry. For behind that door sat Barry Gunderson, a blunt, square-shouldered man with a quarter- century’s worth of experience in Nevada’s schools and a fondness for straight talk. Everybody gets it, from teachers and parents to state politicians. Occasionally he answers in the affirmative with a “Hell, yes,” and Las Vegas High’s teachers got a similarly hearty answer seven years ago. No words were more welcome.

“Most principals would have said, ‘Sounds great. Not here,’” says Robert Bray, a business teacher in PAL. “Without a doubt.”

Gunderson, who retired this summer, set some ground rules, but he vowed to let the teachers run the program. They started with about 80 recruits.

|

Ricard Giraldo, a senior this fall, on the job last spring at T- Rex effects. The Las Vegas company makes animated creatures for amusement parks, casinos, and other venues. Giraldo, shown here working on a dinasour form, says the work dovetails well with his intended career: computer animation. |

PAL draws students from all backgrounds, but a lot of them fit the model of “the middle kid,” as one teacher puts it. They are teenagers who don’t struggle enough, or excel enough, to receive a lot of attention from teachers, counselors, and administrators. Some of them plan on going to college after graduation; others just want to go to work. They are bright, but walk the halls in anonymity.

Two years ago, Moses Araujo was a junior who lacked the credits and the ambition to graduate. He belonged to a gang, he skipped school, and was “a pretty bad guy” all around, as he remembers it. Born in Mexico, he moved with his family from Arizona to Oregon and finally to Las Vegas as a teenager, trouble following him the whole way. A 2-inch, whitish scar above his right knee, where a bullet once grazed him, reminds him of those days of violence and apathy.

Around the time of that near-miss, he vowed to change. A friend told him about PAL, and Araujo decided to sign up. Pretty soon he was overhauling his schedule and his life.

Students in PAL follow a dress code, and Araujo would, too. On Mondays, he and his classmates “dressed for success,” such as nice shirts and slacks; Tuesdays, he wore what he wanted; Wednesdays, he dressed for his internship; Thursdays, he sported the PAL program’s polo shirt; and on Fridays, he donned Las Vegas High’s red-and-black colors.

He also learned to stick to PAL’s rules of showing up to class and work on time, calling ahead if he couldn’t be there, and in general, treating others with respect. Araujo looked people in the eye when introduced, and shook their hands (a practice followed by all PAL students, as weary-armed visitors soon discover) and said goodbye when he left for the day.

“I changed the way I dressed, I changed the way I talked to people, I tried to be a different person,” says Araujo, a jovial 19-year-old with a goatee and a linebacker’s build. He is old enough now to wear pressed pants and and a dress shirt, young enough for flashy earrings and a necklace.

His first internship in the program was at a Spanish-language TV station as a cameraman, racing to fires and press conferences. For his next one, he made a swift change, working with 3rd graders at a local elementary school, helping them in English and other lessons.

He graduated in June, after a semester when he spent his Wednesdays interning in a real estate office. He likes the business, and hopes to get a license to sell houses someday. If he can make money at it, he believes he’ll be able to work as a disc jockey—music is his main love—on the side. A lot of Araujo’s friends quit school early, too many to count. But even when he fell behind in his credits, he says, he knew that was never for him. A high school diploma offered more.

“A lot of people who drop out, they think that working at McDonald’s, you’re going to be able to make it,” Araujo says during a break at the real estate office. “You’re not going to be able to make it. You want good things in life. You want a car, you want a house. You want to get married, and have kids.”

PAL draws students from all backgrounds, but a lot of them fit the model of the ‘middle kid’.

If Araujo sought discipline, others wanted new challenges. School came easy for Irina Dan, and finding high-paying work, like her former gig at the Monte Carlo, was no problem. The PAL program allowed her to look beyond high school.

She started out interning at a local elementary school, which made her realize she didn’t want to be a teacher. But later she landed an assignment at a local bodyguard and security company, the perfect spot for a student who dreams of working for the FBI.

When you get an opportunity like that, you seize it, Dan has learned. The daughter of Romanian immigrants, she saw her parents leave that country as engineers—and support their family by cleaning rooms and carrying luggage when they first got to Vegas.

“It taught me a lot about what I’m going to do in the real world,” Dan says of PAL. “When we go to high school, most of us don’t get hands-on experience. Now, I realize what I want to do.”

Robert Bray knows that careers are usually mountain roads, not desert highways. They veer crazily and double back, full of steep climbs and perilous drop-offs, when we expect them to unfold for miles in one direction. The business teacher has heard many Vegas stories. He has one of his own.

Twelve years ago, he was living in Los Angeles, working at a finance company and tiring of the 24-hour traffic jams. He had grown up in a family of teachers, and eventually that legacy spoke to him, too. The time came to reinvent himself. Where else but Vegas?

|

Robert Bray teaches in the Partnership at Las Vegas Program. But Bray, also the liaison between businesses and the school-to-work initiative, spends a good chunk of his time lining up internships for students, by phone, and in person, and smoothing out any bumps the neophyte workers encounter. |

After moving to town, he took teacher certification classes by day, and to make a living, worked as a waiter on a hotel-casino’s graveyard shift by night. He would get off work at 7 a.m. and stumble into class an hour later, tips jingling in his pockets, eyelids fluttering like nickel slots. One day, his internal clock overcame him. His head hit the back wall of the classroom with a thud, and he shot awake, wondering if anyone noticed.

“It was uniquely Vegas,” recalls Bray, 43, with a weary chuckle.

He took a job at Las Vegas High in 1996, and began teaching in PAL not long after. A former salesman, Bray was soon asked to revive those talents. Once a week, he put on a suit and tie and began making cold calls, trying to persuade lawyers, accountants, and hotel managers around town to take part in the program. Slowly, word began to spread. Today, PAL has more businesses signed up for internships than it has students to fill spaces. That success is largely attributable to Bray, according to the program’s teachers, who describe their lanky, affable colleague as a workaholic, one they want to keep around.

Bray remains the de facto liaison between the employers and the school, and it keeps him hopping. At 8 a.m. on a Wednesday, students are scattered across town at their work sites, but Bray’s cellphone in class keeps ringing. Business owners call. Then parents, students, and PAL alums, wanting information, job references, advice.

It’s a hectic time of year for Bray, clad on this day in jeans and a short-sleeve shirt. School ends in a few weeks, and employers are turning in evaluations of their recent interns. Of course, the teenagers end up passing judgement on their employers, too, in private. Not every internship is a good match, Bray notes after hanging up with one grumpy student.

“She doesn’t like her boss,” he says, trying to smile through a slight grimace. “She says he’s pompous.”

He encourages her to stick with it. Teachers in PAL warn students they have to earn their employers’ respect over time.

“We tell them there are no guarantees,” Bray says. “There are no jobs below you. ... We tell the kids, they’re going to test you, because they don’t know you from Adam. But if you do a good job, your duties will expand—and they do, time and time again.”

In the beginning, there were plenty of doubters. Teachers outside the program griped about its small classes, wondering why everyone didn't get the same treatment.

He keeps detailed lists of students and internships, but most of the time he can work from memory. Students are assigned to law offices, medical centers, and engraving companies, and even hotel-casinos, if PAL administrators can be sure they are learning long-term skills, like hotel management, and not just parking cars or clearing tables. Bray remembers one student’s stint in a city office. “They loved him,” he tells a visitor. Of another recent grad: “He’s now a supervisor at his job site,” he says. “We have a lot of those.”

An oft- repeated motto for the program is “work hard, play hard,” and it fits. Students in PAL have started off the past few school years with a field trip to Utah for a Shakespeare festival, then to Zion National Park for some camping and hiking. The ones who kept up with attendance and other requirements got to finish last year with a visit to San Diego. Students and teachers stage regular fund- raisers to help pay for activities.

Some PAL participants are referred to the program by guidance counselors, others by teachers, if they see a student who might benefit. In other cases, students sign up on their own, after PAL’s instructors make their annual visits to sophomore classes to talk about the program. There is no minimum grade point average, but the program, which accepts only juniors and seniors, quizzes other teachers about students’ attitudes and whether they are likely to put up with the rules. Students and their parents sign liability releases, along with contracts agreeing to stay in the program a year, so they can’t just quit after a couple of weeks if they don’t like it. They also have to provide their own transportation to the job sites.

At the outset, interest booms. As many as 300 students will sign up during a typical year. But that number tends to dwindle before the school year starts, when students skip mandatory interviews, fail to fill out forms, or simply decide they don’t want to do the work, PAL staff members say.

Employers are grateful for the ones who stick it out. On a typical, bustling day, there isn’t much a teenager working the front desk at Sam’s Town Hotel & Gambling Hall doesn’t encounter: the eager guest who’s just arrived; the angry customer who says his reservation fell through; the giddy gambler who just won $120 at the blackjack tables; the sour tourist who emptied his wallet on the slots (which can be heard clanging around the corner). If students can handle it here, they can handle it anywhere, says front-desk supervisor Dana Hampton, who has been accepting PAL interns for years.

“I’m sure it’s kind of an eye-opener for them,” Hampton says. “We tell them, ‘It’s up to you what you learn.’ It gives them a nice opportunity to get the experience, without a lot of the pressure that comes with it.”

In the beginning, there were plenty of doubters. Teachers outside the program griped about its small classes, wondering why everyone didn’t get the same treatment. Others complained about the unorthodox schedule.

“Our first three years were rocky,” says history teacher Wallace. “We had some disgruntlement. Some of it was quite valid. ... Now it’s a team approach, but we had to fight through some misconceptions.”

|

Andrei Casino, far right, dropped out this year. This interview landed him a job in Wal-Mart’s produce section. He still hopes to get a diploma. |

But teachers say they never had to fight Gunderson, who stood by his fledgling program. When PAL’s teachers asked for new phone and fax lines, and other equipment, the 50-year-old principal found the money. He estimates that the program costs between $35,000 and $40,000 a year, including the field trips and other activities. Roughly one-fourth of that money comes from the school’s overall yearly budget of about $400,000, he says, and fund-raisers cover much of the rest.

As the program got off the ground, Gunderson says, he made only a few firm requests of PAL’s teachers. He wanted a school within a school: a self-contained program that could essentially run itself without much intervention.

The principal also sought thematic unity, when it was possible. Students learning World War I history might also be hearing about poisonous gases in chemistry and reading The Great Gatsby in English class. And he didn’t want students going to job sites on Fridays, which might lead to truancy and conflicts with sports, dances, and other activities.

“We just kind of bit the bullet and cranked it up,” Gunderson says, “and it was awesome.”

Other schools in Nevada have sought information on PAL, and while neither Gunderson nor state education officials have heard of anyone else trying precisely the same approach yet, he predicts others will follow. Like some PAL teachers, he is also convinced the program’s model could work for an entire school, with some adjustments.

The pressure on Las Vegas’ schools isn’t likely to abate anytime soon. State education officials say they have tried to do more over the years to encourage casinos to hire only workers with high school diplomas, with limited success. And demand for workers in Las Vegas is likely to grow, with more mega-resorts in the works.

Clark County district administrators have established their own programs in recent years to try to track students at risk of dropping out and persuade them to stay, says Brad Reitz, an assistant superintendent with the school system.

|

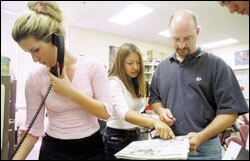

Irina Dan, who tired of a hotel-casino job, works the phone looking for a job while PAL teacher Kirk Wallace and another student scan employment listings in the classifieds. |

While he says “no program is the answer for all schools,” Reitz says the results at Las Vegas High are impressive. “Educators are notorious for abandoning things that don’t work,” he says. But PAL “seems to be successful. It has the respect of all the people involved.”

It has also won the backing of Las Vegas High’s new principal, Patrice Johnson, who took over for Gunderson this summer. She calls PAL “a marvelous opportunity,” and will consider expanding it.

“These are great teachers, who have an ability to get to know their kids,” Gunderson says. “That is the whole crux of a better education. These kids are truly having successes. They are getting legitimate accolades for their performances, and feeling better about themselves. You work hard, you’re successful. You don’t work hard, you don’t get that.”

If PAL’s model doesn’t take hold elsewhere in Clark County, it won’t be for lack of student interest, according to somebody who knows. It seems like every week, Ricardo Giraldo gets stopped somewhere and asked the obvious question: How do I get a job like yours?

He’s getting used to it. Not long ago, the 17- year-old was struggling in class, before hearing about PAL. This past semester, he landed a coveted internship at T-Rex Effects, a company that makes robotic animals and elaborate props for clients like amusement parks, casinos, and even Hollywood movies, in a shop a few blocks from the Strip. Giraldo continued working in the shop over the summer, and now he’s getting paid for it.

It is a zoo of unfinished creations. Some of the human and animal forms have appeared in shows at the Excalibur Hotel and Casino, where Giraldo’s dad works as a porter. The son is now a senior, thinking of going to college in computer animation.

“There’s a whole bunch of kids in the community and the whole city that would take advantage of it,” Giraldo says of PAL. “I’ve seen a lot of people drop out, and I wouldn’t want to. I’d rather graduate, and go for what I’m going for.”

Shirley Giron shared that determination. If she were another student, at another school, the 18-year-old might have been deemed at risk. She was pregnant during her senior year, and gave birth to a baby boy three months ago. The close-knit community of students and teachers helped her cope with the situation, said Giron, who graduated in June.

|

PAL was the right answer for Moses Araujo, who graduated this spring. |

“If you’re with kids in other classes, they’re always asking about the baby, touching your stomach, wanting to know, ‘When’s the baby shower?’” Giron says. “In PAL, there’s no time for that. We’re concerned about school and work.”

And about each other. Bray still keeps in touch with Larry Gipson, one of the students who didn’t make it. He joined the program his junior year, in 1999, and with the help of teachers there, he thrived. He took an internship in the city of Las Vegas’ neighborhood-services program, where supervisors spoke highly of him. But it wasn’t enough. A few weeks before graduation, he quit school.

“He blossomed,” Bray says. “That was what was so frustrating.”

It was a decision that tore at Gipson, now 22, but he says he badly needed the money. This summer, he took a job at a Wal-Mart about a 10-minute drive from his former high school, earning about $8.40 an hour. In some places that’s a solid wage, but in Las Vegas, it’s tough to get by on that kind of pay.

His life is more complicated now. He has a son, almost a year old. But Gipson vows he will return to school and get a degree, through an adult education program, through night classes, somehow.

Taking a break outside the store one afternoon, the solidly built young father smiles when he thinks back on PAL and Bray, whom he listed as a job reference recently. The money he makes now isn’t nearly what he had hoped. Not enough people his age understand the downside to quitting school early, he says.

“I would tell them, no matter what you’re going through, finish school,” says Gipson, wearing an orange work vest over a sports jersey and a pair of longish shorts. “You can have street smarts, but street smarts don’t mean anything.”

“It always bugs me,” he adds. “I know why I did it, but I owe it to myself ... to go back [to school]. I will go back. It’s not a question of ‘if.’”

Time has brought him new resolve. He will soon find out if this town brings him any luck.

Coverage of urban education is supported in part by a grant from the George Gund Foundation.