Lauri Francis asks her 8th graders which terms they don’t understand in the paragraph their classmates just read aloud.

“Blind spot,” one says. Ms. Francis writes the two words on the blackboard.

“Field of vision,” says another.

“Vision lines,” says a third, as the teacher adds that term to the list.

Another student reads the next paragraph in the textbook in what is a standard approach to a lesson in mathematics—not language arts—here at Public School 176 at the northern tip of Manhattan.

Over the past decade, a cutting-edge approach to math has been turning mathematics teachers into reading aides. The new curricula, in an attempt to introduce students to the subject in real-life situations, require more reading and writing than students have ever been asked to do before in math classes.

“There are more words on the page of math textbooks than there were in the 1980s and the late 1970s,” said Andrew C. Isaacs, an author of Everyday Math, an elementary school textbook series produced in the new style.

“One of the functions that the words serve is to provide a story line that helps [students] have a framework to fit the ideas into,” Mr. Isaacs continued. “They retain things better when they’re part of a larger structure.”

But critics of the approach say that some students—because of disabilities, limited English proficiency, or even less severe reading deficiencies—struggle with the basics of reading so much that they can’t pick up such fundamental mathematical skills as dividing fractions or manipulating algebraic functions.

“A lot of my kids might have been very talented in mathematics, but they didn’t read well,” said Matthew B. Clavel, a Teach For America recruit who formerly taught 4th grade at a school in the Bronx. “If you asked them to read a word problem, it interfered with their ability to learn the math.”

The debate on reading in math classes is a symptom of the bigger philosophical clash over how to teach the subject.

One side says it’s necessary to help students discover mathematical concepts so they can learn how to apply the skills of addition, multiplication, and other operations later. The other, meanwhile, insists that constant repetition of math operations helps students master the skills they need before engaging in higher-order thinking.

Dictionaries and Drawing

As Ms. Francis continues with her lesson here in New York City, at one of more than 1,600 districts nationwide that have adopted the new-style curriculum, she divides students into groups. She tells each one to define the terms that class members say they don’t understand.

The teacher also instructs the groups to answer questions about why a hiker standing at the rim of the Grand Canyon can’t see the Colorado River directly below. The exercise is the introductory lesson of a unit called “Looking at Angles,” a part of the Mathematics in Context curriculum used in many of the middle schools in New York’s Community School District 6.

As the students search through dictionaries and explain why the hiker’s field of vision doesn’t include the river, Ms. Francis circles the room to help them.

In one group, she demonstrates a blind spot by drawing a picture of a New York City intersection, where parked cars on a cross street block the view of a driver edging out from a stop sign.

In another, she asks: “What does the word ‘blind’ mean?”

“You can’t see,” a student says.

“So a blind spot is a place you can’t see,” she explains.

Ms. Francis’ strategies are common ones for teachers using the new mathematics curricula, according to Georgiana Dipoulous, a math facilitator for District 6. The district enrolls 29,000 K-8 students from the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, which lies between the Hudson and Harlem rivers. Located in the heart of a community of immigrants from the Dominican Republic, the district reports that about a third of its students are learning English as a second language. At the start of the lesson, Ms. Francis addresses basic reading needs: ensuring that students understand all the words in the passage. While Ms. Francis asks students to identify the terms they don’t recognize, other math teachers in the school create a vocabulary sheet for the children, Ms. Dipoulous said.

Ms. Francis asks a fluent reader to read a passage aloud, allowing others to follow along. Other teachers assign small groups to read passages, allowing the stronger readers to help others.

“It is taking the atmosphere of a communications or language arts classroom and bringing it into a mathematics discussion,” said Ms. Dipoulous, who leads monthly sessions to help teachers prepare for their next set of lessons in the curriculum.

The professional development is vital, district officials say, because the curriculum requires math teachers to present their lessons in a new way.

“The teachers have to learn how to present the material,” said Madelaine Gallin, the mathematics coordinator for District 6. “If [the students] become engaged in the reading, they want to learn the math.”

While that approach may work in some classrooms, critics say, it’s not helpful where students still need to learn the skills for conducting math operations—and lack reading skills as well.

“There’s as much reading in the stuff as there is mathematics,” said Steven L. Schwartz, an 8th grade teacher in the Bronx.

“It’s fine for kids who have the basic skills” in reading and math, he said. But it just confuses students who struggle with reading, he added, and they never learn the mathematics they need.

Students who have reading disabilities are especially disadvantaged by the new style of curriculum, some maintain.

Many of those students succeed in programs that emphasize mathematical algorithms, but then fail when a new curriculum requires them to read about the math concepts before they work through sets of problems.

“All of a sudden, they’ve lost something that they were good at,” said Susan K. Sarhady, the president of the Plano Parental Rights Council, a Texas group protesting a similar math curriculum in the suburban Dallas district.

Likewise, children from non-English-speaking backgrounds are presented with math that they struggle with, and their parents aren’t likely to be able to help.

Such parents “always assumed that if they could not help with English, the humanities, and language arts, that they could at least help with math,” said Julie Tay, the director of Wossing Academic Tutoring in the Chinatown section of Manhattan.

Other educators contend that the amount of reading makes it difficult even for good readers to find the time to do the addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division that is the heart of the discipline.

“The verbosity of these math curricula is detrimental to all students,” argued Bastiaan J. Braams, a research professor of mathematics at New York University. “Understanding can only come from very good facility in carrying out operations.”

But the experience of students discovering mathematics through their own investigations is more valuable than teaching them procedures to do mathematical operations, supporters of the new curricula insist.

“There’s a lot more gotten out of that than doing a set of problems,” said Peter N. Simon, the math coordinator at Intermediate School 218, a middle school in District 6. “And it takes about the same amount of time.”

‘Not a Barrier’

At IS 218, Ms. Dipoulous, the district’s math facilitator, witnesses an example of how a teacher can merge mathematics and reading.

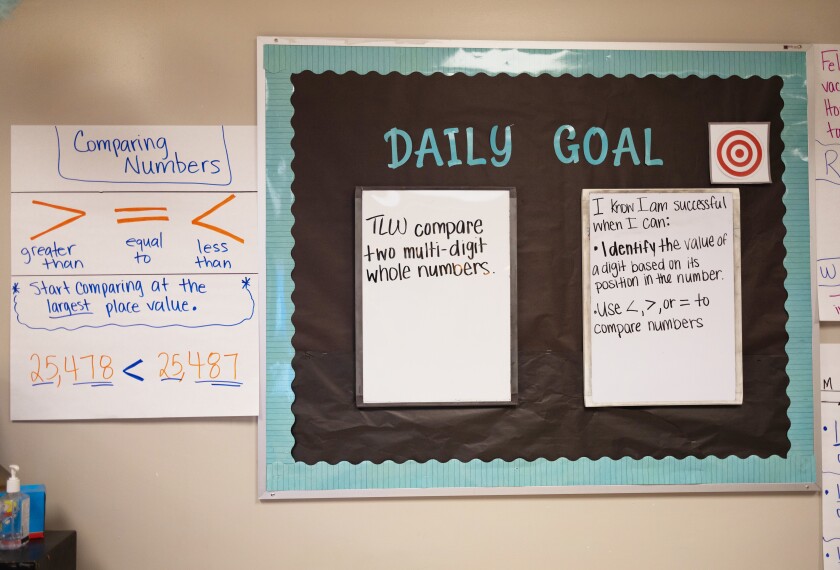

Lance Green, a 6th grade teacher, begins a series of lessons titled “The Size of Shapes” by writing four vocabulary words related to the geometry lesson on the board. Beside them, he writes sentences with blanks where the new words would accurately fit in.

Ms. Dipoulous says the lesson’s introduction is important because those students will later see similar questions on citywide and state exams. It’s one of the best ways to do the project, in her view.

Twenty minutes into the lesson, Mr. Green’s students have read him the sentences and solved the riddle of which of the new words fit into the blanks. He assigns students to work in groups to identify “problem-solving strategies” for calculating the area and perimeters of shapes.

The reading embedded in the math lessons “is not a barrier at all,” said Mr. Green, who is using the curriculum for the first time this year. “It just takes more time.”

But he acknowledges that one reason it works well is that his students are in the top track for 6th graders. Last year, with his class of lower-performing students, he would have had to work harder on the language skills.

“I would have had to spend a lot more time,” Mr. Green said, “on simple terms.”