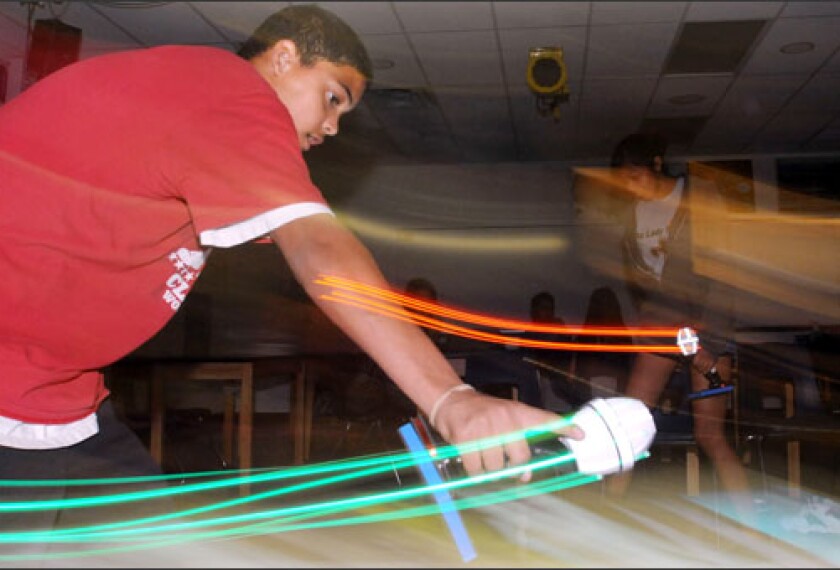

To build on classroom experiments and lectures, Daniel Sweeney has his 9th grade earth science students act out scientific concepts on a 15-by-15-foot mat on the floor of the room. Object-tracking cameras mounted on scaffolding around the space collect data based on the students’ movements while immersing them in the experience through a video projector and speakers, which provide visual and audio feedback in real time.

The Situated Multimedia Arts Learning Lab, or SMALLab, which refers to the floor mat and trussing around it, is being used only at the 1,360-student Coronado High School in Scottsdale, Ariz., for now. A second one is in the works as part of a new school, called Quest to Learn, that is scheduled to open in New York City in the fall.

The program is part of a growing movement in schools to incorporate digital games and simulations into classrooms as a tool for raising achievement and preparing students for the technological challenges ahead of them.

And although incorporating digital simulations and games into curricula is far from the norm in K-12 schools, educators, researchers, and game developers agree that attitudes toward using those media as teaching tools are changing. Proponents say progress is being made toward a meaningful integration of games and simulations into mainstream classrooms.

“We’ve seen a sea change just in the last year,” says Katie Salen, the executive director of the New York City-based Institute of Play, which is the organization behind Quest to Learn. “Games are what kids do. It’s this deeply imaginative space that kids love.”

Even so, experts caution against using such media for learning simply because those new tools seem like an exciting way to teach or learn. Digital games and simulations, they say, should be used to improve the learning of academic concepts.

“Game-based learning isn’t going to work for everyone, it’s not going to work all the time, and it’s not going to work for all your needs,” says Richard N. Van Eck, an associate professor in the instructional design and technology program at the University of North Dakota, in Grand Forks. “It’s just one tool in your toolbox that goes along with all the other tools that you have.”

Keeping that in mind can prevent educators from being disillusioned by games, which are often billed as a “silver bullet” technique to solve all the problems in a classroom, says Christopher J. Dede, a professor of learning technologies at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, who studies simulations and games in education.

“You have to start with the issue and ask yourself, ‘Is there a way that gaming or simulation might help me in wrestling with this issue?’ as opposed to saying, ‘Whatever the problem is, if I just put gaming in, it’s going to get better,’” he says.