A complex racial schism threatens to dismantle the signs of academic progress in the Mount Vernon, N.Y., district.

Walking every block in this community, they went door to door rallying residents with a stark message: Mount Vernon schools are rife with nepotism, cronyism, and racism. African-American children are failing. Blacks are denied a fair share of school jobs and contracts.

Claiming that the all-white school board and the white superintendent served as the political arm of the city’s Italian-American civic association, African-American ministers and activists mounted a grassroots effort that led to the ouster of every white member of the school board by 1999. Today, every school board member in this densely populated suburb of New York City is black. And, for the first time, so is its superintendent.

Some call the community-mobilization effort a modern-day civil rights movement. Others believe gullible voters were deceived by an onslaught of racially charged lies.

What’s clear is that what began seven years ago as a quest to run the schools and better educate black children has evolved into a complex racial schism that threatens to dismantle the signs of academic progress that have brought national acclaim to this small city bordering the Bronx.

|

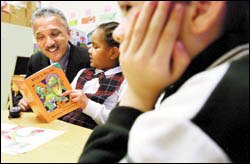

Out and About: Ronald O. Ross reads with students at Lincoln Elementary School in Mount Vernon, N.Y. He has overseen a sharp rise in test scores since becoming superintendent, but has alienated some of the city’s other black leaders. |

That attention has stemmed primarily from the 9,700-student district’s test scores, which appear to vindicate the African-American activists’ efforts. From 1999 to 2001, Mount Vernon’s 4th graders posted the greatest gains in English/language arts test scores in New York state. Students’ math scores soared over the two-year period as well.

This predominantly black school district is now the darling of New York state Commissioner of Education Richard P. Mills, as well as Hugh B. Price, the president and chief executive officer of the National Urban League. National newspaper and television stories have trumpeted the district’s test-score prowess.

“This is an affirmation of what can happen when parents and community leadership get fed up,” says Price, who lives in neighboring New Rochelle, N.Y. “Through this effort, they’ve made heroes of the teachers.”

But behind the headlines is a set of local dynamics that might surprise those who have seen Mount Vernon held up as a resounding success story. A strong undercurrent of racial rifts, power struggles, and distrust threatens to mar students’ academic feats. Some board members and the city’s African-American mayor question the value of the school system’s test scores and allege that the district is “teaching to the test,” complaints echoed by some white critics as well.

Fueling the tensions, many people here believe, is the take-no-prisoners management style of Superintendent Ronald O. Ross. Hailed by admirers as a charismatic hero of urban education, he is denounced by local critics as a brash bully.

The upshot is that the schools chief may be on his way out of the very city he has helped put on the nation’s school improvement map.

All signs pointed to Mount Vernon as a district in need of resuscitation when a coalition of black board members became a voting majority in 1997.

For years, legions of middle-class parents, both white and black, had abandoned the district for private schools and neighboring public schools. A fatal stabbing at Mount Vernon High School in 1994 fostered the belief that schools here were unsafe. The state required six elementary schools to formulate academic-improvement plans because of lagging test scores.

So the recent test-score backlash—especially from those within the African-American community—infuriates the straight-talking Ross. After listing the accomplishments of his four-year tenure, which include the passage in 2000 of a $100 million bond referendum for school renovations and construction, the superintendent declares: “If I had been a white man and done the same things, some black people would have erected a statue to me.”

Instead, rumors abound that Ross, 57, will be replaced by the school board when his contract expires next year.

Personalities may be open to differing interpretations, but many observers see Mount Vernon’s test scores as evidence of genuine progress. Last year, 74 percent of Mount Vernon’s 4th graders met or exceeded the state standard on New York’s English/language arts test, while 79 percent hit that mark in mathematics. Since 1999, when students first took the 4th grade test, Mount Vernon’s language arts scores have skyrocketed by 38 percentage points, the greatest gain of any of the Empire State’s 720 school districts. Based on their scores, 10 of the city’s 11 elementary schools made the state’s list of “most improved” schools.

At Longfellow Elementary School, where 99 percent of the students are nonwhite and 82 percent of the children qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, the percentage of students attaining or exceeding the state standard on the language arts assessment jumped by 67 percentage points in two years. Now, three of the district’s elementary schools post average language arts scores that exceed those of some schools in wealthier neighboring communities that spend thousands of dollars more per pupil.

Paradoxically, Mount Vernon’s victories have come as parents in nearby Scarsdale, a more affluent, higher-achieving Westchester County suburb, have banded together to protest the damage that they believe the state’s testing program is doing to classroom quality.

But people who are vocally skeptical of Mount Vernon’s gains argue that the community has much to lose if it blindly buys what they regard as test-score propaganda. They point out that the district has no written curriculum. And test scores at the high school and middle schools still rank among the lowest in Westchester County.

“I don’t gauge educational success solely on reading scores,” says Frances Wynn, a school board member. “I don’t care how much [the score] improves or how great it is. The state blew [the results] out of proportion.”

This summer, when the state releases results of language arts and math tests taken earlier this year and those yet to be administered in May, the district expects better showings not only by 4th graders, but also by 8th graders—the focus of district staff-development efforts this year. Last month, Mount Vernon learned that 94 percent of its 5th graders met or exceeded the standard on the state’s social studies assessment that they took in November.

“So far, I have seen no reason to do anything but praise everything [Mount Vernon] has accomplished,” says Roseanne DeFabio, the assistant commissioner for curriculum, instruction, and assessment for New York state’s department of education. “I’m rooting for them.”

Surrounded by upper-middle-class communities in Westchester County, residents here emphasize the city’s small-town feel by reminding visitors that “Mount Vernon is just 4 square miles.”

Often described as more urban than suburban, this city of 68,000 residents has subsidized housing within blocks of $500,000 homes.

Like many American cities, Mount Vernon was divided geographically by race in the past. But today African-American families make up 60 percent of the city’s population and reside in every neighborhood.

This demographic shift is clear in Mount Vernon’s classrooms, where nearly eight in 10 of students are classified as African-American, 10 percent as white, and 10 percent as Hispanic.

As the city's complexion changed over the past 30 years, the school district's leadership remained unchanged—predominantly white.

Yet as the city’s complexion changed over the past 30 years, the school district’s leadership, including both the school board and the superintendent, remained unchanged—predominantly white.

Many here assert that a local community group, the Italian Civic Association, maintained a political grip on the district—the city’s largest employer—and its budget, which now stands at roughly $100 million.

The ICA was founded in 1918 as a local advocacy group to help immigrants from Italy fight discrimination in Mount Vernon. Over the years, the membership-based organization emerged as a political power, endorsing and financing school board candidates, most of whom were ICA members. In addition, many ICA members were top school administrators, including William C. Pratella, the district’s superintendent from 1972 to 1997.

Peter Plati, the current ICA president, acknowledges that, at first glance, the ties between the district’s leadership and the association could be seen as a “power play.”

But he stresses: “It’s not that decisions were made from the ICA.”

Looking back on his long tenure in Mount Vernon from his current post as the chairman of the education division at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., Pratella strongly denies that his administration was racist. He says that all employees and students were treated fairly, and that the schools received equitable funding.

Pratella still keeps a list of his minority-staff appointments over his quarter-century at the district’s helm as proof of his inclusion efforts. In 1997, he says, a fifth of the district’s staff was made up of African-American employees. During his tenure, he points out, three of the district’s 15 schools were renamed to honor prominent African-American educators in the city.

“All of our schools were majority African-American,” he adds. “How could you discriminate?”

But that’s exactly what many African-Americans in Mount Vernon charge that Pratella and white school board members did. As many people here tell it, school leaders, in cahoots with the ICA, gave lucrative contracts and jobs to their relatives and redirected funds to north-side schools where most of the white children attended classes.

The Rev. W. Franklyn Richardson, the pastor of Mount Vernon’s Grace Baptist Church, likens the previous school leadership’s actions to educational “apartheid.”

“I wasn’t against white folks,” says Richardson, who ran unsuccessfully for the school board in 1979. “I was just against what they were doing to our children.”

|

Keeping faith: The Rev. W. Franklyn Richardson of Grace Baptist Church worked to elect blacks to the school board and now backs the superintendent. |

To craft a more cohesive election strategy, Mount Vernon’s black ministers formed the Coalition for the Empowerment of People of African Ancestry, or CEPAA, which would compete against the ICA’s candidates. The coalition, put together in 1995, held its own nominating conventions at Grace Baptist Church to choose African-American school board candidates to run for the board on the CEPAA slate. The board’s nine members are elected to staggered, three-year terms.

But the coalition suffered a crushing defeat in 1996: Every candidate on the CEPAA slate lost, and the lone African-American on the board resigned shortly afterward.

Carole J. Morris, the director of the Mount Vernon Neighborhood Health Center, says some doubted that there were enough black voters in the city to elect a black-majority board. Yet Morris, who has been the chief of staff for the city’s Democratic Party for the past 25 years, had a simple message for voters: “You have to vote black.”

CEPAA raised about $50,000 in 1997 and on Election Day, 500 volunteers canvassed the city encouraging people to vote. All five CEPAA candidates won, rocking the ICA, and reducing the number of whites on the board to four—thereby forming the board’s first-ever black majority.

CEPAA’s work wasn’t finished with the election. The candidates the group had supported set about fulfilling their campaign pledge to replace Superintendent Pratella.

Weary of battling the new board, and after 36 years with the Mount Vernon schools, Pratella retired from the district.

“I gave my whole life to that place,” he says.

Two years later, in 1999, another four CEPAA candidates were elected, wiping out the ICA-supported candidates and starting Mount Vernon schools on a new path.

Teaching wasn’t Ronald O. Ross’ first calling. Born in New York City’s Harlem during World War II, he was raised in Warrenton, Va. In the late 1960s, Ross was a Howard University student in Washington trying to earn enough money to enroll in law school when he decided to escape the draft by signing up for the Teacher Corps, a federal program that sent teachers to urban and rural areas. Teaching became Ross’ vocation, and he went on to become a New York City high school principal.

‘I put race on the table. I put corruption on the table. That makes people uncomfortable.’

As the deputy superintendent of the Hempstead, N.Y., schools on Long Island from 1996 to 1998, Ross led an effort that improved test scores at a local high school. Still, Ross, a tall, slender man with salt-and-pepper hair, wanted the chance to be No. 1, he says.

Although friends and colleagues called Mount Vernon a “no-win situation,” Ross stood by his mantra: “There’s nothing wrong with public schools that can’t be fixed.”

Impressed by his unfailing passion for educating children, the Mount Vernon school board, including its four white members at the time, unanimously agreed to offer Ross a five-year contract in the fall of 1998. Soon after he tackled his new role, Ross rankled some members of the district’s staff and school board. Using a whispery, smooth voice that can alternately sound melodic and inspiring or gruff and intimidating, Ross unleashed his no-holds-barred leadership style in an address to staff members.

In that speech, he warned teachers, especially white educators, that they must make him believe that they cared about their students or face unemployment. They would, he declared, stop making excuses for why poor black children couldn’t learn. He charged that Mount Vernon school officials were like “pigs at a trough” in the way they consumed district resources.

“I put race on the table. I put corruption on the table. That makes people uncomfortable,” Ross recalls matter-of-factly. “That’s not arrogance. I put children first. I didn’t come here to be liked.”

Stunned and outraged, many school staff members resigned or retired after that speech. Ross says good riddance. But Wynn, the school board member, complains that Ross damaged employee morale.

Ross’ straightforward delivery may be hard to take, but the Rev. W. Darin Moore, the current board president, agrees with the superintendent’s assessment of the district under the old regime.

“It was more benign neglect than intentional abuse,” Moore says of the previous administration. “But the result was the same. You had a whole group of black children warehoused and moved through the system without getting a proper education.”

Ross, who has four adult children and four grandchildren, appears to be a completely different person with students. He often spends time reading to children at the district’s elementary schools. The superintendent even hosted a sleepover for students at the district office last year.

“He has such a way with children,” says Brenda L. Smith, the district’s deputy superintendent. “That is his greatest strength. He loves and believes in children.”

With adults, however, Ross tends to alienate dissenters, because of his unwavering insistence on his vision of school reform, Moore says. But, the board president adds, Ross’ passion for raising student achievement “has motivated him to tear down obstacles that others would tiptoe through, and finesse their way through, and compromise.”

As Ross set about transforming the Mount Vernon schools, he replaced every top district administrator within a year. Every school was assigned at least one assistant principal. Teachers who Ross believed were ineffective were transferred, embarrassed, and moved around until they either left or shaped up.

He also implemented a new hiring practice to diversify the workforce and eliminate what he saw as cronyism; today, roughly 40 percent of the staff is African-American, about double the proportion four years ago. A school-based committee interviews potential hires and makes its recommendations to the district’s human resources director or Ross himself.

But some of the superintendent’s staff appointments drew the ire of board members, who questioned the new employees’ experience and political allegiances. Now, critics point out that Ross’ entire top management team has resigned or been replaced in the past four years.

Many say Ross’ most important personnel choice was Alice Siegel, the district’s English/language arts administrator. Siegel was planning to retire from the high-performing Greenwich, Conn., schools the year Ross signed on with Mount Vernon.

In 1999, the first year of New York’s new assessment program, two-thirds of Mount Vernon’s 4th graders scored below the state standard in English/language arts, and almost half were failing math. Secondary students’ scores were even worse.

Siegel and Ross emphasized improving the instruction of reading and writing in the elementary schools, believing those subjects to be the foundation of future learning.

“Teachers would say, ‘I taught them that,’” recalls Siegel, who is a co-author of a series of educational books for children. “I would say, ‘You might have, but they didn’t learn it.’”

Soon after Ross took over as superintendent, a relentless, hands-on professional-development program emerged.

A relentless, hands-on professional-development program emerged, with Siegel modeling instruction and coaching teachers in the classroom. Reading specialists were dispatched into 4th grade classrooms. National teaching experts led additional training sessions.

Teachers also were given common planning time. That allowed for exchanging ideas, working together, and, most of all, providing one another with support. It’s the same approach being used with 8th grade teachers this year.

The district uses both the phonics and whole-language approaches to teach reading. Fourth graders spend 90 minutes daily reading, writing, and discussing a subject. Students also are given books to read at home. Last year, they were challenged by the superintendent to read 50 books—double the number encouraged by the state board of regents—to earn a chance to win a new bicycle. In all, 168 met the goal and received new bicycles.

When it came to testing, teachers explained to students what good writing looks like, stressing the elements that would bring them top scores on the state assessment. After school, students struggling academically were tutored.

|

Class considerations: After having her 4th graders read from the story “The Boy Who Drew Cats,” teacher Modesta Curzio poses questions during a lesson at Parker Elementary School. |

Tisa Kearns, a 4th grade teacher at Mount Vernon’s Cecil H. Parker Elementary School, says students must be challenged with questions that “cause them to think.” She encourages her pupils to be “divergent thinkers,” mindful that there is more than one way to solve a problem.

“It’s good, old common-sense teaching,” Kearns says. “It’s not throwing worksheets at kids.”

Next door to Kearns at Parker Elementary, words cover the walls of Modesta Curzio’s 4th grade class, making it a kind of alphabet-soup wallpaper. Personality traits, like helping, foolish, and mischievous, are divided into positive and negative lists.

Curzio instructs the students to listen carefully as she reads a passage called “Sharing Crops,” about a former slave who grows crops for a landowner in exchange for a share of the proceeds.

Students eagerly scribble notes in their workbooks as Curzio reads the passage a second time. Then Curzio peppers her students with questions that they easily conquer.

The most critical question, the story’s lesson, brings a variety of impressive responses from these pint-size deep thinkers. Amber says: “When you try to trick someone, you only end up cheating yourself.”

Some observers suggest that Mount Vernon’s secret may be that the district didn’t purchase an expensive academic program, and has instead spent more than $3 million on teacher professional development since 1998. By contrast, the district spent just $52,500 to train teachers in 1997.

“It wasn’t just coming in and waving a magic wand,” Siegel says. “This should serve as an example, that clear focus and team building can yield good results.”

Mills, the state education commissioner, praises Ross for educating teachers rather than buying a “canned curriculum.” Mount Vernon didn’t implement any unusual strategies, he says; it’s Ross’ message that resonates powerfully: “Every child is going to learn to read at a high level—period.”

If educators want to implement the Mount Vernon model in their own communities, they’ll have to wait. No guide or, for that matter, no unified curriculum exists—a lack that generates skepticism in some quarters. District officials say work to document the district’s approach is under way.

“We asked, ‘How did you do this?’” says board member Wynn. “I know you can’t get scores like this by giving kids bikes. The basic procedure should be clear.”

To Mount Vernon Mayor Ernest D. Davis, test scores are “unpredictable,” and therefore the district’s gains are irrelevant.

Pleading his case for control of the city’s schools, Davis—an African-American whose sister-in-law is school board member Frances Wynn—explains that the schools receive more than half of Mount Vernon’s revenue. But the mayor has no influence over how those dollars are spent, complains Davis, who wears his gray hair in dreadlocks.

A former architect, Davis also believes he is better suited to direct the district’s $100 million construction and renovation plan.

It’s criticism from Davis and members of the all-black school board that most distresses some black people in the community.

It’s easy to unify people around a cause when there’s a common enemy, like the ICA, observes Morris, the local Democratic Party official. Now, however, the common enemy is gone, she says, yet some people don’t realize the battle was won and fight one another instead.

Ross’ assessment of his African-American critics is more blunt: “The black people criticizing me are the same Uncle Toms and Aunt Jemimas who never said a word under the predominantly white administration.”

Some community members believe that the Coalition for the Empowerment of People of African Ancestry quickly began mimicking the Italian Civic Association’s failings, engaging in cronyism and nepotism. Some say Richardson, the Grace Baptist Church pastor, is calling the shots and protecting Ross.

“We almost reversed and did the same thing [as the ICA],” says Wynn, who has cut her ties to CEPAA and says she never felt comfortable being linked to the group.

Richardson dismisses claims of political meddling, pointing out that CEPAA disbanded last year and won’t play a role in the upcoming school board elections next month. In fact, he joins the ICA in saying he would prefer a more racially and ethnically diverse school board.

Some believe that the Coalition for the Empowerment of People of African Ancestry quickly began mimicking the Italian Civic Association's failings, engaging in cronyism and nepotism.

For its part, the ICA has retreated to the school-board-election sidelines. The feeling in Mount Vernon is that you can’t fight the black churches, says Len Sarver, who served on the board from 1996 to 1999 with the ICA’s backing. Sarver, who supports a mayorally controlled district, says more families are opting out of the city’s schools. It’s a trend he predicts will continue.

“I’m afraid that Mount Vernon is probably doomed,” warns Sarver, who sought unsuccessfully to found a charter school in the city last year.

There’s also growing concern about a recent state financial audit showing that Mount Vernon has serious lapses in record-keeping that could have led to a $12 million budget shortfall.

Ross vehemently disputes the audit’s findings. He calls the report flawed, and emphasizes that under his leadership, the district has ended every year in the black.

But the audit has given ammunition to the district’s doubters.

Atiim B. Sentwali, a longtime school board critic, vilifies both past and current board members as the host of a local cable-TV talk show called “Community Forum.” Charging that the board has abdicated its fiscal responsibilities to Superintendent Ross, Sentwali is urging voters to reject the school system’s budget in May.

“The majority of the people in Mount Vernon have been drugged by the complexion of the board members and the superintendent,” declares Sentwali, who is African-American.

As the community debates the validity of his success, Ross forges ahead with plans to academically revamp the two middle schools and the city’s only traditional high school. The district will construct an additional high school and another middle school. Sixth graders will join the 7th and 8th graders at the middle schools, Ross says.

Whether Ross will be in Mount Vernon to shepherd that plan through to completion is unclear. Although he received a $25,000 raise last year, boosting his salary to $175,000, board members are reluctant to discuss extending Ross’ contract beyond the summer of 2003.

Now a media magnet who receives standing ovations after speaking at national conferences, Ross won’t talk about being courted for other jobs. Regardless, Ross believes that he will never please Mount Vernon.

“The level of venom and personal, poisonous, libelous attacks has been very hard to bear,” he says. “I don’t know when I’ll leave.

“But when I do,” he says, pausing, “it won’t be because they ran me out of here.”