Can a church save a community? Perhaps not alone, but the congregation of Grace Memorial Presbyterian Church believes it can help lead the way. The members of this city’s oldest black Presbyterian church, in fact, see no alternative.

Seven years ago, they challenged their ministers to do something about the crime and drug problems that were encroaching on their schools, and in the church’s scenic, tree-lined neighborhood, which has been the home to thousands of professional and middle-class black families over the years.

Grace Memorial’s story—and its hope in the power of the mind, the spirit, and local activism—symbolizes a national discussion over the role religious groups play in their communities.

Today, the community’s vision unfolds each weekday afternoon as 150-plus youngsters pile out of church-owned vans to into every possible open space of the rust-colored, brick church as part of its 7-year-old After-School Tutorial and Enrichment Program, or A-STEP.

The program, which has a lengthy waiting list, is popular with local families. It also has won the respect of educators here, who say they appreciate the way the program reinforces the work being done in Pittsburgh’s public schools.

Program leaders are proud of another foundation of the program—a spiritual component that they say is inseparable from A-STEP’s academic mission.

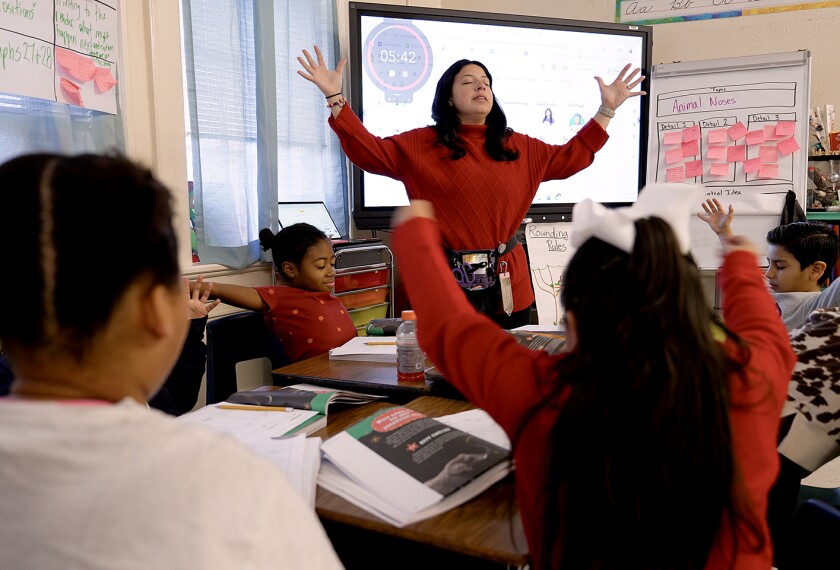

That spiritual strand is woven into the program each Monday and Wednesday afternoon, when the Rev. Johnnie Monroe calls the students into the sanctuary for a voluntary, 15-minute “pastor’s chat.” During a recent talk, he asks students, who range in age from 5 to the early teens, what God expects of them, and what they expect of themselves. Hands erupt pleadingly from the pews. He lets each student offer an answer; the suggestions include good behavior, respect, love, and good grades. One adolescent confidently declares, “I’m going to graduate from college and become an engineer.”

Arms folded, the minister’s stern but fatherly visage breaks into a warm smile: “That’s my boy.”

The program has many of the ingredients that are at the center of a federal effort to tap into the faith-based community.

President Bush has established a White House office to determine how to channel more federal dollars to faith-based groups that carry out social services, including after-school programs. His plan has touched off a lively debate over issues of church-state separation.

Criticism has come from opponents of any semblance of a government establishment of religion, and from religious leaders who fear that the federal rules tied to such aid would force them to dilute their spiritual focus. The Bush plan received a boost last week when the House and the Senate unveiled bills supporting key elements.

Monroe points out that his church, which operates A-STEP without government money, simply supports and complements the work of local public schools. And it’s a part he urges churches nationwide to play, especially black churches in inner-city neighborhoods, which often are the most stable organizations available to young people at risk of failing in school or getting in trouble.

“One reason I pushed the program here is that I saw so many children who needed what the church could offer in terms of morals and values,” he says. “We also saw a need to assist the school system. We see ourselves as a school after school.”

Grace Memorial Presbyterian Church sits like a sentinel atop a steep, narrow cobblestone road at the edge of Schenley Heights—a neighborhood that once was a jewel of the sprawling Hill District east of downtown.

Throughout the 1900s, black families that worked hard and spent prudently moved up the hill, just as early immigrants to the area before them had done. They might start with a bungalow close to downtown. In time, they’d move into a townhouse of Centre Avenue, carved into the rocky hillside.

Many of the most successful families settled into two-story brick homes on the stately plateau that is Schenley Heights. Shaded by arching trees and near good schools, Schenley Heights stood as high geographically and otherwise as the white communities on the ridges across the city.

Over the years, however, downtown redevelopment took a heavy toll on the area. The displacement of residents along the lower part of the Hill and the decimation of a once-thriving local economy fed the growth of an underclass that put new strains on schools and social services.

Today, boarded-up buildings and empty houses dot the climb to Schenley Heights. Long-faded paint makes it hard to even read what businesses were once located inside.

While Schenley Heights and its surrounding neighborhoods still make for a handsome, bustling community, the area’s altered economics wrought many changes. The neighborhood around Grace Memorial is solidly mixed-income, as white-collar professionals share their blocks with families on welfare. The price of houses within a stone’s throw of each other can range from $25,000 to $200,000.

But as longtime residents remain loyal to their neighborhoods, they are faced with crime, drug use, and the crippling effects they have on family life. That is why they’re fighting for the schools, the streets, and the ties that made Schenley Heights the home they never wanted to leave.

If salvation is ahead, many see it represented by Grace Memorial, and the youngsters who flock here each weekday from seven public schools and two religious schools in three surrounding communities.

The program charges a nominal fee to families for transportation to and from the program, the daily snacks, instruction, and weekly field trips— no matter what religion the children and their parents practice. Monroe, the 59- year-old pastor, says that, despite the spiritual messages, no proselytizing goes on.

One reason I pushed the program here is that I saw so many children who needed what the church could offer in terms of morals and values.

As they file into the church, the 4th and 5th graders settle quietly into the spacious, renovated ground floor. The kindergarten, 1st, and 2nd grade pupils go to rooms adjacent to the sanctuary. The 3rd graders bustle up a narrow flight of creaky, hardwood stairs to their tight-but-happy quarters on the second floor. Meanwhile, the middle school students attend classes in a converted house next to the church.

Each grade has an educational team consisting of a credentialed teacher and a cadre of assistants, including tutors from local colleges. They are all versed in Pennsylvania’s state learning standards. The pastor’s daughter, Nikki J. Monroe, 28, is an academic coordinator for the 39,000-student Pittsburgh school system. She designs the church’s coursework to support what is taught in schools.

The church also offers a modest but tidy children’s library, and a very busy computer center. A- STEP offers regular art instruction, and music classes led by a local public school music teacher who doubles as Grace Memorial’s music director.

“These are educators who have a vested interest in the community,” Nikki Monroe says. “They really want to be here.”

With so many students in crowded quarters, you’d expect some noise. And there is plenty of it in some rooms. Checkers rattle as they fall onto wooden floors. Children raise their voices in protest at being called a name by a classmate. Quick taps on a blackboard can be heard in another room where a group of girls is drawing.

But for the most part, the students are focused on their work, says Alethia W. George, a retired high school teacher and the A-STEP program’s director. Her husband, Samuel W. George, is the church’s former pastor. He helps out as a driver, tutor, mentor, and occasional disciplinarian.

Alethia George says most children in the program are identified by their schools because they are behind academically or because they need help that they’re unlikely to receive at home.

“I’ve seen so many African-American children tracked into low-achieving groups. Many of them have great minds, but they’re not learning,” she says. “Sometimes they get put in these groups because of behavior. Then they’re tested, but they don’t have strong backgrounds, or anything at home like magazines, and they don’t test well. They fail the test. ... Where else do they go?”

In January, 46 of the program’s students made the honor roll at their schools—a record.

One of the program’s most important contributions is in helping students complete homework. Districtwide, students lose points toward their grades for failing to do homework. “With the kids at Grace, that’s not going to happen,” says Annette Scott Jordan, the principal of the nearby McKelvy Elementary School. “Getting that work done is the first commitment of the tutors.”

Grace Memorial’s program is very much the kind of effort that is getting attention at the national level from policymakers and researchers alike.

The Brookings Institution, a policy think tank in Washington, recently held a full-day conference titled “Sacred Places, Civil Purposes: The Role of Faith-Based Organizations in Public Education.” A prominent roster of speakers warned of numerous unresolved issues that lie in wait for groups that could get federal funds under President Bush’s plan.

The backbone of the black community has been spirituality. Here, lots of parents lack it. There's a generation of unchurched parents who are happy to have that element infused in the program.

For example, churches often send tutors to schools, open their facilities to schools for meetings, or use the pulpit to lobby parents to monitor their children’s schoolwork, which are seen as acceptable activities. On the other hand, could a minister begin a reading program with a prayer if federal money helped pay for the books?

“This is an ongoing conversation, and it’s not going to be easy work,” said Dennis L. Shirley, the associate dean of the school of education at Boston College, at the conference.

While noting that research on the academic impact of faith-based programs is thin at best, the conference highlighted initiatives that are believed to have led to improvements in local schools.

One of the successes highlighted by Mr. Shirley was the Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation, which brings together various community groups, including churches, to put political pressure on public officials to improve schools.

At the same time, issues such as school prayer, other forms of religious expression, and the place, if any, of creationism in science curricula have put churches in the middle of heated legal and political battles. Some conservative Christian officials have even called for an exodus of children from public schools.

“Many such conflicts have intensified over the last decade with the growth of Christian fundamentalism,” Mavis G. Sanders, an assistant professor in the graduate division of education at Johns Hopkins University, concludes in a paper presented at the conference.

Similar questions are sure to arise at Grace Memorial, where some members are eyeing the potential to receive federal aid. After all, the $250,000 that the program has received, mostly from local philanthropies, may not see it through the current school year.

“We go out on faith each year,” says Gregory A. Morris, an associate professor of education at the University of Pittsburgh, who chairs the board of directors that oversees the nonprofit corporation the church established to run A-STEP.

But Monroe has his own, strong opinion on the matter: “There will be no trade-off of God for money,” the pastor says.

The strong relationships that the church has built so far with the public are owed to the careful collaboration it has with the local public schools, Monroe says.

One of the program’s biggest supporters is Pittsburgh schools Superintendent John W. Thompson. A religious man, Mr. Thompson, who is African-American, has visited Grace Memorial several times, and has directed the school district’s staff to help train the church’s teachers.

That he has not shied away from a strong partnership with the church stems partly from his own background. He recalls how the high expectations of the Baptist church he attended as a youth in North Carolina propelled him to succeed.

Now, as the chief of the district, Mr. Thompson goes with his wife to a different church, synagogue, or mosque each week so that a wide range of his students will see him worshiping.

In addition, he wants to see how well the various congregations are involving local children. “I’m disgusted when I see that black churches are not going into communities seeking kids,” Thompson declares. “They all want to go to Africa and do missions, when there’s work to do in their own back yards.”

Other observers say that a certain seamlessness between African- American churches and their communities is one reason that the program—and its religious message—are embraced.

Jordan, the principal of McKelvy Elementary, is not surprised that parents of various religious backgrounds send children who attend her school to A-STEP.

“The backbone of the black community has been spirituality. Here, lots of parents lack it,” she says. “There’s a generation of unchurched parents who are happy to have that element infused in that program.”

Such attitudes are not exclusive to this Pittsburgh neighborhood.

“The black churches have been the institution for black life when there were no others—for leadership, action, and social support,” says Charles C. Haynes, the senior scholar at the First Amendment Center in New York City. “In many ways, African-Americans don’t see there’s a problem with the involvement of church in ways that might trigger a lawsuit somewhere else.”

Monroe, for his part, says that he must walk a tightrope between supporting public schools and taking them to task for failing minority children.

I've seen so many African-American children tracked into low-achieving groups. Many of them have great minds, but they're not learning or they don't test well.

Nationally, black ministers cover the political spectrum on public schools. Some join lawsuits seeking new state aid formulas for schools, or stronger desegregation remedies. Others back giving publicly financed vouchers to students in failing schools so that they can attend private or religious schools.

“The minister has got to be an advocate for justice and against injustice for voiceless children. We support those persons and institutions that are on our side,” says Monroe, whose political and spiritual feet are planted clearly in the pro-public-education, anti-voucher camp.

In measured, slow cadences, he continues: “I think the Pittsburgh schools are getting on the right side. There had been a board that micromanaged and a superintendent that allowed it. Now, we have a take-charge superintendent and a board getting on the right side.”

The superintendent himself, an imposing man who stands about 6 feet, 5 inches tall, makes his own distinctions on this point.

“I don’t go to my church and tell them how to run the church,” Thompson says. “I don’t want a church telling me how to run the district. I want collaboration. But what’s godly about pointing fingers and criticizing? They need to support schools, not criticize them.”

A-STEP’s success is built, in part, on lessons learned from research.

In addition to teaching education courses at the University of Pittsburgh, Morris is the former director of reading and literacy for the Pittsburgh school system. Alice M. Scales, a professor of education at the university, joins him at Grace Memorial.

The pair serve as consultants to the program. Their research on A-STEP has been published in The Negro Educational Review and in The Journal of Research and Development in Education. More importantly, the research has been used to improve the program and to establish credibility with potential donors.

In 1998, Morris and Scales’ research revealed a lack of communication between the tutorial program and the students’ classroom teachers. The following year, each participating school assigned a staff member to serve as a liaison to Grace Memorial. The liaisons’ job is to recommend students for the program and track their progress.

The black churches have been the institution for black life when there were no others—for leadership, action, and social support.

The church also added weekly field trips and entered a partnership to use a local school for recreational activities to raise student and teacher satisfaction. One survey even found that the students preferred computer classes to snacks or recreation.

“There are lots of people doing positive things, but they don’t take the data and write about it,” Scales says. “We use this to see what works, what doesn’t work, and where to go in the future.”

As for the future, the church wants to expand the A-STEP program to 250 students, upgrade its computers, and open a 24-hour day-care center for parents who work at night.

Such a vision is one reason that Eunice C. Anderson, the principal of Margaret Milliones Technology Academy, gives the highest marks to Grace Memorial for helping working parents.

“I’ve never worked with a church that has such a sophisticated after-school and summer program,” Anderson says. “I’m just amazed and overwhelmed by the services they provide. If all our churches could provide the same service, just think of the children we could reach.”