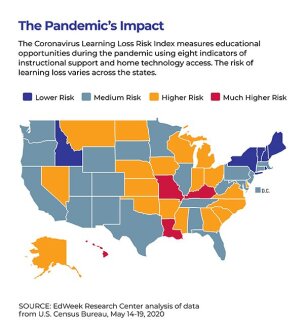

Students in Southern and Midwestern states appear to be at greater academic risk in key areas than those in other parts of the country as a result of pandemic-driven school shutdowns, concludes an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by the EdWeek Research Center.

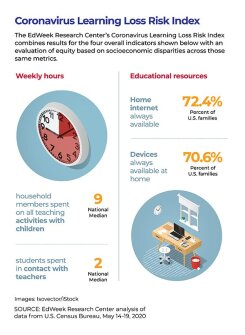

The Research Center’s new Coronavirus Learning Loss Risk Index examined time spent learning and interacting with teachers and family members during this spring’s physical closures of K-12 schools, and the availability of devices and internet access that enable remote learning. The Index is designed to provide a relative—not absolute—sense of how the states compare when it comes to factors that might put students at risk of learning loss during the pandemic.

Students in Vermont were found to be the least susceptible to learning loss based on those factors, while Hawaii was the most prone to academic risks during the coronavirus outbreak, based on the analysis, which tracks the impact on public school student learning from May 14 through May 19.

The data show students in all states, even Vermont, are at some risk, and that nearly half of states (23) are at “higher risk” or “much higher risk” of students not having access to the tools and conditions crucial for learning. The bottom nine out of 10 states flagged in the risk index are in the Midwest and the South, as defined by the Census Bureau. The data show technology gaps in the South and disparities in access to both teachers and parental support in the Midwest.

Aside from Vermont, states showing a lower risk of learning loss include Idaho, Maine, New Hampshire, New York, and Rhode Island. Hawaii ranks as the most at-risk, alongside other higher-risk states, such as Kentucky, Louisiana, and Missouri.

Throughout the nation, the gaps in educational access between households where at least one person has a college degree or higher versus families with no post-high school degrees was wide-reaching across all measures. Forty states were found to be either at higher or much higher risk in providing education equitably to all students based on the Census data.

The Picture Before COVID-19

The pandemic aside, there are underlying conditions that impact the infrastructure of states’ K-12 systems and how state and local officials respond to the needs of teachers and students alike. States that were doing poorly before the pandemic based on the measures used in Education Week’s overall Quality Counts summative grades and scores continue to perform poorly on the new COVID risk index.

Louisiana, which scores near the bottom on the Quality Counts index in terms of educational outcomes (K-12 Index) and cradle-to-career pathways (Chance for Success Index), ranks last when examining the percentage of weekly hours at or above the national median that household members spent on all teaching activities with children. Louisiana also ranks in the bottom five in terms of always having access to the internet and devices for educational purposes.

Louisiana’s struggles are not unique, though. Students across the country are having issues accessing technology and the internet. Roughly 3 out of 10 households with public school students did not have home internet or devices always available for educational purposes as late as a couple of months after the virus outbreak began. Most states in the bottom 10 for always having access to the internet and devices are located in the South.

Mississippi ranks last when it comes to internet access always being available for educational purposes. West Virginia ranks at the bottom when it comes to devices. And both states score near the bottom on EdWeek’s overall Quality Counts measures with a grade of C-minus each.

There also are gaps in access to technology devices and the internet nationally when comparing households based on educational attainment levels, especially for states that have been having difficulties trying to reopen school buildings. Virginia has the biggest difference, with children from less-educated homes seeing a nearly 40 percentage point gap in access to technological devices than their peers from more-educated households. Georgia, which has faced problems in opening school buildings amid the coronavirus spread, ranks near the bottom (49th) in terms of gaps in access to internet availability for doing schoolwork.

Big Gaps Based on Family Education Levels

For most states, the number of weekly hours students spent in contact with teachers at or above the national median corresponds with the percentage at or above the median spent learning at home with family members.

This association is amplified for households where no one has a college degree. In most states, 25 and the District of Columbia, lesser-educated households lag behind more-educated ones in terms of students having access to instruction from both teachers and family members.

This pattern appears to impact the Midwest disproportionately. Nine out of 12 Midwestern states see significant gaps in access between more- and less-educated households regarding household member and teacher learning hours. For instance, Missouri ranks 47th in educational disparities in access to learning time with household members and second from the bottom for teacher access.

Hawaii shows the largest disparity in weekly teacher interactions between more-educated and less-educated households. The gap for the nation is roughly 8 percentage points, while the gap for Hawaii is nearly 54 percentage points. Additionally, only 37 percent of household members in Hawaii spent more time in teaching activities with children than the national median or above.

Kirstyn Galius, a third-year teacher who works at a Title I school in Hawaii, went from interacting weekly with 60 students at the beginning of the school year to only two by the end of May, about two months after schools shut down in-person instruction. As she prepares for the new school year, she often finds herself calling parents to see what they need, even though some of them speak a different language than her.

One note of caution: Some of the Census data around how, and what, individual households define as “learning at home” can be ambiguous. One example: whether “learning at home” included more multifaceted learning involving outside activities with family.

“Do you think the way they [Census] are asking the question is capturing family engagement?” asked Lois Yamauchi, a parent activist and professor of educational psychology at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa. “Because the research on family engagement in education tends to be dominated by school-based activities, whereas I would argue learning and education is broader than school-based activities.”

The top- and bottom-ranking states on the COVID risk Index, Vermont and Hawaii, also differ significantly from the rest of the country in size, population, and academic outcomes. However, there are policy implications that can apply to the rest of the nation.

What to Learn From the Best and the Worst

In Vermont, the state may have been better positioned than others to deal with some pandemic-driven learning challenges due to Act 77 passed in 2013, which encouraged the use of personalized learning and may have increased access to devices, especially in rural environments. before the coronavirus even happened.

Hawaii, meanwhile, is a geographically diverse state with a single statewide school district. Its state schools superintendent, Christina Kishimoto, who was elected in 2017, came in under the framework of empowering schools and allowing for more school-level decision-making.

The state is considered to be at much higher risk than any other state in terms of equity based on EdWeek Research Center analysis. Hawaii has the widest gap in the amount of teacher interaction with lesser-educated households compared with more-educated ones.

Still, the district is under pressure to ensure all students can access a variety of resources that would enhance the learning environment. Under the CARES Act, the federal pandemic-relief law passed in March, the state has been able to create an IT help desk so parents can reach out if they have issues. And the district is also working to provide health-based wraparound services to help deal with the state’s immense homelessness, which affects students’ access to remote learning and teacher interaction.

One notable blank spot in the learning-risk picture for U.S. citizens: There is no public data available on the indicators tracked in the COVID risk index from the Census Bureau for Puerto Rico or any other U.S. territory. This is the case despite the fact that Puerto Rico alone, with more than 300,000 students, would be considered one of the 10 largest districts in the United States if it were part of the mainland.