to and even an obsession with learning to edge out heavy competition for the limited number of seats in the country’s best colleges.

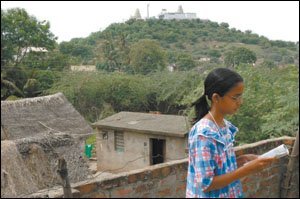

“This is my favorite place to study because it’s so peaceful here,” the 15-year-old says, gesturing around her at the small space that offers a view of the tops of the palm and papaya trees growing abundantly in her neighborhood in southern India. She spends hours here each evening. About half a mile away is her favorite part of the view—an ornately carved temple sitting atop a hill.

But over the edge of Subashini’s haven, the view changes dramatically. Slums are all around, as far as the eye can see. A woman washes aluminum dishes for the evening’s dinner on the mud streets outside her hut. More women, with colorful plastic pots, line up at a single public tap to collect drinking water that trickles out for an hour once a week.

Subashini, who stands under 5 feet tall, dreams of lifting her mother and two siblings out of this poverty and away from the barren structure they now call home. “I want to become a computer engineer and move to the United States,” she says, the words tumbling over each other in their eagerness to get out.

| Audio Extra | ||

Staff Writer Vaishali Honawar tells of her recent reporting trip to India, of the schools she observed and the students she interviewed. The trip highlighted the widening of opportunities for India’s students as the country, which has a 65 percent literacy rate, continues to churn out a disproportionate amount of top notch engineering students. (Windows Media file: 5.38) | ||

| | ||

She works hard. When she’s not studying on the roof, Subashini is at school or, at night, in the house’s only bedroom, studying more. The only break she gets is the bicycle ride to and from school, and even that is no picnic. Dodging the heavy traffic on rough, potholed roads, she spends as long as 45 minutes traveling. Her uniform—a white tunic, blue drawstring pants, and a long blue scarf folded neatly over her shoulders—gets caked with dust and exhaust.

India is now in the throes of a higher education revolution, and its colleges are churning out thousands of professionals each year. Despite the fact that 35 percent of its population still cannot read or write, the country has successfully positioned itself as one of the world’s foremost producers of math, science, and technology graduates, forcing current leaders in the field—including the United States—to take a closer look.

For many families, getting a child into engineering college is something of a life’s mission: A degree is considered a ticket to wealth and success. For the student, it takes a total commitment to and even an obsession with learning to edge out heavy competition for the limited number of seats in the country’s best colleges.

According to Malathy Balakrishnan, principal of the 2,500- student Sri Sankara Vidyalaya high school that Subashini attends, most of the kids who enter the plus-1 and plus-2 grades—comparable to 11th and 12th in the United States—hope to get into the computer science track that prepares them for engineering college. Usually the entire family engages in the process, from deciding where the student will attend college to which subject he or she will pursue. Parents put their own lives on hold, canceling vacations and forgoing entertainment. Those who cannot afford to pay for higher education take out large loans.

Students spend hours each day, seven days a week, attending coaching classes in which they are repeatedly drilled and tested in math and science, the two subjects they must master to make it through the grueling entrance exam. Especially in the final two years of school, most aspiring engineers give up all extracurricular activities and immerse themselves in books for more than 12 hours a day. It’s been a while since Subashini has had time for drawing, one of her favorite hobbies.

While Balakrishnan personally believes it would be healthier for students to devote some time to other activities, including sports, she says there’s not much she can do other than make sure the teenagers get two 45-minute periods of mandatory physical education each week. “When it comes to engineering seats,” the principal explains, “even one-tenth of a percent of a difference in your marks matters.”

Fear of such intense competition is what drives Nirmal Kumar, a 12th grader at the same school, who wants to become an electronics engineer. Since he entered 11th grade, he has put away his coin and stamp collections. He no longer plays his favorite game, cricket. And he rarely hangs out with his friends, most of whom are too busy anyway because they’re also studying to become engineers.

The tall young man with oiled hair, each strand combed neatly in place, casts a guilty eye toward his father as he admits he misses playing the drums. Ravindra Kumar immediately points out that music is not something from which his son can make a living.

Nirmal’s daily routine is not unlike Subashini’s. He rises at 4 a.m., drinks a cup of coffee his mother has made for him, and then plunges headlong into study until 7:30 a.m., when he leaves for school. After returning at 4:30 p.m., he studies until 6:30 and then leaves for his coaching class, which runs until 9:30. Back home at 10, he eats dinner and, unless it’s exam time, goes to bed by 11. He doesn’t mind the punishing routine. “I want to have a good career, a good future,” he says.

Behind Nirmal’s decision to become an engineer is his father. A quintessential Indian patriarch, Ravindra Kumar believes he’s the best person to decide his children’s future. He has carved out a comfortable middle-class life, and his family wants for nothing. But, Kumar says, he wants more for his first son.

He is generous when things go his way: Nirmal has been promised the latest model of the best motorcycle on the market if he gets into a good college after passing the engineering entrance exams, which most aspiring engineers in the country will take after 12th grade.

When Nirmal is home, studying in a small room at a desk piled high with books, Kumar has instructed his wife, Kasturi, his other son, Manoj, and his elderly parents to tiptoe around, making sure Nirmal has no distractions. When Nirmal wants a glass of water, all he has to do is call out, and his mother rushes to get it for him.

The television set in the living room has not been turned on in months, on Kumar’s instructions. When a tailor’s shop next door plays music too loudly, Kumar rushes over to ask the owner to turn down the volume.

But the urge to be just a normal teenager is overwhelming, and sometimes even the diligent Nirmal cheats. He loves Hollywood movies like Titanic and Jurassic Park. “And I like the way Britney Spears dances,” he adds.

On an occasional Sunday, he sneaks out of the house to watch a movie. What does his father think about that? “Oh, he thinks I am studying at a friend’s house,” says Nirmal, a rare, shy smile breaking out.

With a population of nearly 7 million, Chennai, formerly known as Madras, is India’s fourth-largest city. Tamil Nadu, the southern Indian state of which Chennai is the capital, has seized the lead in the engineering race, with the largest number of such colleges in the country. More than two-thirds of them have opened in the past seven years alone.

Thousands of Chennaites with engineering degrees, particularly in computer science, have moved to the West, including the United States, or have prospered in India’s rapidly growing economy. Their wealth and India’s recent globalization are changing this once-conservative city, with its long tradition of classical Indian art, into a modern metropolis where teenagers hang out at discos and pizza parlors and use cell phones to instant-message friends. Five-star hotels line the road to the airport, throbbing with international travelers.

Pammal, a suburb just outside the city, is riding the same wave into the future. Its population has multiplied manyfold over the past few years. Brick-and-cement houses have sprouted by the dozens on once-arid land, and motorcycles and Korean cars roar with middle-class affluence.

In Nirmal’s home, decorative tiles tattooed with red swirls cover the floors of every room and even the porch outside. The living room is furnished with upholstered chairs and a couch. Kumar plans to buy his son a computer this month with the bonus that he’ll get from his employer during Diwali, a Hindu festival that celebrates prosperity.

“But I will monitor Internet use,” he says. “I don’t want it to become a toy.”

A farmer’s son who moved to Chennai 30 years ago, Kumar operates a steam boiler for a factory in the city. He once dreamed of becoming an engineer himself but couldn’t afford to go beyond high school. Although he’s by no means a wealthy man, he has, through a lifetime of hard work and years of rigorous saving, set aside enough money to give his sons a good education. Should his second son get into engineering college, though, he says he would have to sell some land inherited from his family.

Engineering college in India is expensive, costing $500 to $1,500 a year—a fortune for most middle-class Indians. Some colleges charge for “extras” like transportation and lab facilities, and the expenses add up quickly. Wealthier students who fail to make the grade on entrance exams can choose to “buy” engineering seats with large donations to a college.

Kumar places a high value on education—for boys. If he had a daughter, he says, speaking Tamil through a translator, his top priority would be to get her married. Nirmal was in 7th grade when his father sat him down and mapped out his future. Kumar would like him to go to the United States “because no one else in our family has ever been there—and because you can make a good salary.”

There appear to be few doubts about Nirmal’s future as an engineer. Although he is incredibly shy and almost disappears into the 50-student classroom at school, teachers describe the 16-year-old as bright and call him a good candidate for engineering college.

“He makes around 85 percent at school, and we are not very liberal with marks. He will easily score above 90 percent in the engineering entrance exams,” says his computer teacher, S. Balaji. Balaji remembers a short movie Nirmal made a year ago using Flash. “This was way beyond his [grade] level,” the teacher says. “He had to learn several features that were not in his curriculum.”

Only two miles from the buzzing development of Pammal are the slums of Thiruneermalai, where life has stood still for decades. Women in saris bunched up above their knees bend to work in waterlogged rice fields; men milk cows outside huts. The huts stand in haphazard rows, dry palm leaves woven together for the roofs and mud walls caked with cow dung, a natural antiseptic. In their midst, Subashini Menon’s house stands apart, testimony to another kind of tragedy.

It is a brick structure, one story tall. But no plaster is on the bricks, and naked electrical wires dangle dangerously from the walls. The stairs to the roof are unfinished, and there is no railing. One of the house’s two bedrooms is unusable, filled with sand left behind by a construction crew. Three years ago, Subashini’s father, a bus driver for the state, died in an accident, and her mother could no longer afford to continue the construction. She used the $4,000 she received in compensation from her husband’s employer to pay off the expenses already incurred for construction and other loans.

The bright sunshine of Chennai struggles to enter the small living room through a window covered with a rag. Shelves have been dug out of the naked brick, and the only decorations are pictures of Hindu deities from old calendars and some cards Subashini made using images from greeting cards. On the door, her father’s name, “R. Menon,” is spelled using letters cut from newspapers.

Subashini’s mother, Manickavasuki Menon, the family’s only wage earner, makes little more than $30 monthly. She works eight hours a day, six days a week, doing odd jobs for a cotton-garments factory. Subashini’s older brother, Sureshkumar, wanted to become a computer engineer himself, but he had to settle for a certificate course at a local institute. Their mother struggles to pay the $100 annual fee even as her son dreams of going to college one day.

A week after her husband died, the 38-year-old widow tried to poison herself.

Subashini’s 8th grade teacher, Jayageetha Sridharan, remembers how Subashini continued to attend school through the tumult, rarely missing a day. Though she is a diligent student who sits in the front row and speaks up in class, the pressure nevertheless began to take its toll. “She just couldn’t pay attention in class,” says Sridharan. It was only when she pulled Subashini aside that the proud young girl broke down and told her all that had happened.

Sridharan visited her student’s home and spoke with her mother. “I told her she had to live for her children, that she was the only support they have.”

Three years later, the sadness is still evident in Manickavasuki Menon’s hunched shoulders as she shows a photo of her husband. When Subashini is not listening, Menon admits she will never be able to afford to send her daughter to engineering college.

Ironically, though, the family has one advantage: The Menons belong to a low caste. Indian law allocates a percentage of seats in colleges for children from lower castes to make up for centuries of oppression by Brahmins, the group that sits atop India’s punishing caste system, which is based solely on birth. But competition for those seats is also fierce, and the fees, though reduced, are still high.

Subashini also cannot afford the extras that most other aspiring engineers, including Nirmal, can: coaching classes, for example, that drill students for hours each day. They are considered almost a necessity for passing the entrance exams because schoolteachers often cannot cover in close detail the lengthy math and science syllabus.

Right now, Subashini’s textbooks come from charitable students who have moved on to a higher grade. “Most of the things we have are secondhand,” says her sister, Sujatha, 16, who wants to become an officer in the Indian civil service. She adds quickly, “But we are satisfied with what we have.”

Even food is scarce. Each morning, Subashini gulps down a watery rice gruel for breakfast but doesn’t pack a lunch for school. At home, her meals are usually rice and lentils, and perhaps a vegetable dish.

Principal Balakrishnan, a motherly woman who takes a deep interest in her students, recalls how, years ago, Subashini’s father walked into her office with his three youngsters, begging that she take them in although he could not afford the fees on his bus driver’s salary. Sri Sankara Vidyalaya is a private school that charges around $11 a month in tuition. Though Menon himself had not made it past 10th grade, Balakrishnan says she was moved by his determination to educate his children. She took in all three kids on a scholarship, a decision the principal says she’s never regretted because Subashini and her siblings are very good students. Despite Subashini’s intelligence and strong will to succeed, however, Balakrishnan wonders how someone so poor will be able to pay for an engineering education. “But she has a mother who knows the value of education, and that helps,” she adds.

Subashini’s face clouds when she talks about her family’s dire financial situation. Still, she says, she’ll continue to focus on her goal and hope things work out. She recalls the time she took part in an 800-meter walking race and won, despite the doubts of her family and teachers who had thought she was too weak to make it. “I am slow but steady,” she says with a smile.

From her roof, she points to the temple on the hill with its image of the Hindu god Vishnu, known locally as Ranganathan.

“I also have his blessings.”