Most people in the math education space agree that students need to be fluent with basic math facts. By the time kids are in upper elementary grades, they should be able to produce the answer to 6x3 or 4x8 quickly and accurately.

But there’s a lot of debate over how best to achieve that goal.

Do children need to memorize these facts and drill them? Or can they learn through playing with numbers, practicing different ways of figuring out the answers enough that they internalize them?

“Most people in the field will say: ‘Both, we need both,’” said Nicole McNeil, a professor of cognitive psychology who studies math learning at the University of Notre Dame. “But that doesn’t give any actionable feedback about what that means.”

A recent paper tries to fill the gap. Reviewing the research on fact-fluency development, researchers have outlined research-backed advice for classroom practice.

McNeil authored the paper, along with Nancy Jordan, a professor of learning sciences at the University of Delaware; Alexandria Viegut, an assistant professor of educational psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire; and Daniel Ansari, a professor of developmental cognitive neuroscience and learning at Western University in Ontario, Canada.

Students need to be fast and accurate with their math facts, freeing up their brainpower to tackle more complex problem solving, the paper’s authors write. But they also need a firm foundation in “number sense”—an understanding of how numbers represent quantities, and the relationships between them, they say.

“One of our key goals was to push back on the false ‘memorization vs. understanding’ dichotomy,” McNeil said, in a follow-up email after an interview. Students’ number sense and their ability to quickly recall facts support each other, and develop iteratively, she said.

“Children move back and forth between deliberate reasoning and automatic access, and good instruction supports that movement rather than assuming learning happens through immersion alone.”

Read on for four key recommendations from the paper, published last year.

1. Early number sense skills matter, and interventions can boost them

The paper outlines three important early math milestones that usually occur in early childhood or the first couple of years of formal schooling. Research shows that this knowledge forms a foundation for fact fluency, the authors write. They are:

- Understanding “cardinality,” or the idea that the last number counted in a set of objects represents the quantity. For example, a child who counts 1, 2, 3 blocks in a bucket would know that the total number of blocks in the bucket is three.

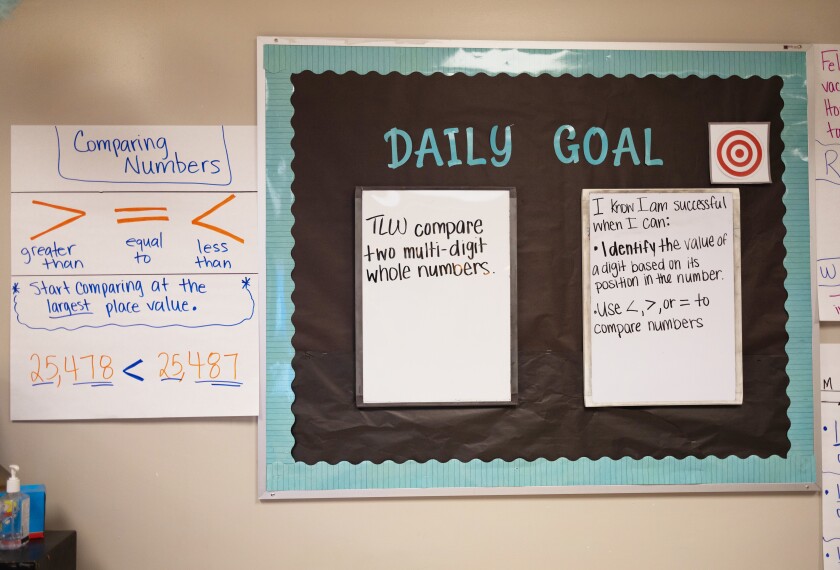

- Comparing written numbers, or knowing, for instance, that the number 5 represents a smaller quantity than the number 6.

- Using addition strategies, such as “counting on” to add 7+3 by counting three up from 7, to reach the answer 10.

They recommend that schools and pediatricians’ offices screen for these skills. For example, they write, Ages and Stages—a common developmental screener given by pediatricians—asks whether 4-year-olds can count to 15, but it doesn’t test their understanding of cardinality.

“This oversight marks a significant gap in public and pediatric practice,” they write.

When children struggle, there are proven interventions that early childhood educators and teachers can use to help students reach these early milestones, McNeil said.

One research-tested strategy involves helping students make the connection between physical representations of quantity, like groups of blocks, and the written numbers that represent them.

The paper references the “concrete-representational-abstract” method, in which teachers first represent a number with three-dimensional objects, then with pictures, and finally with numbers. “This process supports the transition from everyday understanding of numbers, relations, and operations to the more formal symbols used for communicating mathematical ideas,” the authors write.

2. Explicitly teach how to solve math facts

Some students may intuitively pick up on strategies for calculating addition and subtraction programs. Others won’t, and need direction, said McNeil.

She compared it to learning how to read. Spoken language can be learned through immersion. But most children need explicit teaching linking spoken language to letters in order to crack the code of written language.

It’s the same for math, she said. Some conceptual foundations of math can be absorbed through everyday experiences with numbers. “But once we get to the formal mathematical symbols, those are human inventions, so learning how those symbols map onto meaning requires intentional instructional support to ensure they are learned well,” McNeil said.

In the classroom, the paper explains, teachers can model some of these strategies, such as how to use 10 when solving 9+n addition facts. In working through 9+5, for example, teachers could say, “Think, what is 10+5 and then just subtract 1, because 9 is 1 less than 10.”

3. Structure practice intentionally

To be able to recall math facts quickly, students need dedicated practice producing them. But it might not look like the drills some teachers picture.

Research suggests practice should be short—2-10 minutes at a time—and frequent, several times a week.

Crucially, McNeil said, teachers should introduce new facts systematically. That could mean starting with foundational fact sets, like the 2s, 5s, and 10s times tables, or using another organizational strategy. Students should only practice 3-4 new facts at a time until they can recall them automatically.

4. Yes, timed practice is important. But it shouldn’t be high stakes

Timed drills are a third rail in math education.

The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics says they can “negatively affect students, and thus should be avoided,” although there’s no conclusive research showing that timed tests cause math anxiety. In its most recent math framework, the California Department of Education discouraged using timed activities.

But the paper argues that timed practice should have a place in the classroom—with some caveats.

“The avoidance of timed practice is based on the misconception that any form of stress or anxiety is inherently harmful,” the authors write. “This perspective lacks nuance.”

When practice is a little stressful and challenging, research shows, it can actually help the content stick better in students’ memory, they write. They cite several studies showing that students’ speed and accuracy with math facts improved when they participated in time-pressured practice.

But McNeil offered some cautions. Timed practice helps improve speed once students are already accurate, she said—teachers should only introduce timed practice of math facts once students can reliably produce the answers correctly.

And time pressure should be limited to practice, she said. High-stakes timed tests, she said, are a “bad idea.”