When Leigh Knapp became her school’s first full-time media specialist, she had a vision to change the library into a place where kids felt seen and encouraged, and could discover a joy of reading.

This school year, her first in the role at Bethune Academy in Milwaukee, Knapp’s efforts to replace and add thousands of books, refresh the library’s seating and decor, and implement a schoolwide reading challenge have “changed the entire culture” around reading, she said.

Struggling readers and English learners at the pre-K-8 public school are picking up titles that appeal to them and at least attempting to read them. More students are reading on grade level, according to state test scores and the results of internal screeners.

Even staff members’ attitudes are changing, Knapp said.

Now, teachers incorporate more structured and free reading time into lessons, and encourage students to visit the library to find books they might enjoy.

The change that’s afoot at Bethune Academy corresponds with what research has shown about robust school libraries—they can improve students’ reading skills, raise test scores, and even spark a lasting love of reading.

Knapp stepped in as her school’s first full-time media specialist at a time when many schools are cutting library staff to relieve budget pressure.

During the 2020-21 school year, more than 10% of the country’s public K-12 students—at least 5.6 million—attended school in districts that didn’t employ any librarians, according to a 2023 analysis of federal data by researchers working on the federally funded School Librarian Investigation—Decline or Evolution, or SLIDE, project.

Nationwide, K-12 schools employed 10,000 fewer librarians in 2018 than in 2009, the researchers found.

The districts lacking school librarians tend to serve mostly students of color and have higher percentages of economically disadvantaged students, according to the SLIDE report.

Knapp spoke with Education Week about her first year on the job, and shared advice for others trying to change students’ attitudes toward reading. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How did you end up as the school’s first full-time media specialist?

I spent more than two decades as a middle school teacher and a STEM teacher, and then I wanted a change. I don’t like doing the same thing forever.

I enrolled in a media specialist certification program after talking with a school librarian I worked with previously and learning more about the job.

I ended up coming back to Bethune Academy as a school support teacher in a teacher leadership or academic coach-type role, so I was doing that while I was in school for library.

We had a part-time librarian who was in two times a week. She retired last year, and my position as a support teacher was getting cut, so I talked to my principal and said, ‘Hey, I’m almost done with my library program, and all of these jobs still need to get done.’ I pitched the idea of melding the two positions into one, and we went for it.

I do the essential [job duties] of the school support teacher—like helping to administer state tests—but am a full-time media specialist.

I said, ‘If you make this full time, I will completely change everyone’s perception of what the library should be,’ and that’s exactly what ended up happening.

What was your vision for the library?

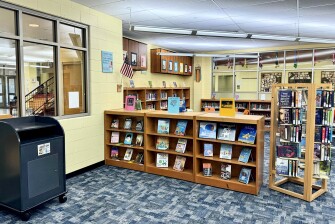

The library collection was completely outdated. The average age of books was [from] 2006. The school opened in 2005, so books were not getting updated at all. When someone’s part time, they don’t have time to do all of that—they basically have back-to-back classes and that’s it. They can’t do inventory. They can’t read the books. They can’t run programming. I wanted to do all of that.

I started a morning checkout time so that kids could not just check out books every other week.

I don’t want them to have to wait for their next class time in the library to get new books. Now, you finish a book, you can come down between 7:30 a.m. to 8 a.m. any day of the week. If I’m here, it’s open.

I also decorated the entire place, added genre labels to help kids more easily find books, and upgraded as many books as I could manage. We added in 2,500 new books before the end of the last year to prepare for this school year, and I’ll have added another 1,400 books by the end of this school year.

How did you get buy-in from teachers to take advantage of all this work?

Teacher buy-in can be difficult. When there’s a million things going on, sometimes it’s hard to feel like you have time to fit this in.

One thing that went a long way, I’ve been doing the Beanstack reading challenge, which goes over a three-month period. It’s essentially a challenge to see who can read the most, and sets a schoolwide goal.

Our initial goal, with 600 kids in the school, was to read 25,000 minutes. We hit that in a very short amount of time.

You can't just sit behind the counter and check out books, because you're not really helping the cause. You have to really buy into what the library can be.

Teachers were making reading a part of their classroom culture and participating in that competitive nature, so we quickly had to up the goal to 225,000 minutes. By the end, we had hit more than 300,000 minutes.

I did weekly raffles, so for every 30 minutes read, kids would get an entry into the weekly raffle, and we’d pull a few names from different grades. I had a bunch of fun little prizes they could choose from, and it kept up the momentum. I also ran a staff challenge to get teachers and staff members reading and involve them, and have fun with them, too. I’d pull one of their names each week and they could have a prize, too. That was fun.

What are you seeing in terms of circulation and student achievement?

Our circulation increased 549% compared to last year because kids had regular access to the library.

Just for fun, I looked at checkout data going back to the 2017-18 school year. We actually checked out more books this school year alone compared to the last six in-person school years combined.

It’s been like magic.

I’ve had “regulars,” mostly middle schoolers, who will come in almost every single day to switch out books. I don’t even know if they are reading them, but they have a space they want to come and say hi, and have a touch point with something in school that gets them excited.

Within the first couple of months of being in this role, from our fall screener to our winter screener, we had a 10% reduction in the size of the lowest group of students, which are those who are reading significantly below grade level.

What has it been like for your English learners and struggling readers?

They’re seeing all these new titles, and a wider variety that can appeal to many more readers. Pair that with more access more consistently.

I’ve had a teacher say about some students, ‘I don’t even think they’re reading.’ But they’re there, they have the books open, and they’re turning pages, and that’s a great first step. Eventually the reading will come.

Some of those students just wouldn’t even bother trying before.

If there’s a language barrier, we have a lot more graphic novels and comic books now, where there are pictures to help. If your English proficiency isn’t that great, pictures can help fill you in. You can pick some words you understand and use some of that other context to help fill it in, and that can be really encouraging.

It used to be novels or nothing. Now there are other options.

We have 40% of our kids who are English-language learners, and they come from all kinds of backgrounds, so I’ve been trying to get books that represent our different cultures. Kids seeing themselves in books can make it feel more relevant and relatable.

I’m really trying hard to turn this book collection around.

What do you think was the key to your success?

I couldn’t have done this if I was part time. It takes time and a commitment.

You have to be willing to be honest with yourself about how things are going and what can be improved. You can’t just sit behind the counter and check out books, because you’re not really helping the cause. You have to really buy into what the library can be.

Now that we’ve had a taste of how much things have changed both in the academics and in the culture, that’s really started to shift attitudes toward reading, and I’m excited to see how that continues to evolve.

People just don’t know the possibilities until they see it sometimes. There have been teachers in our building that have been like, ‘I didn’t know that the library could be all of this.’

We have kids whose entire perception of the library is changing to, ‘Wow, I really like being in this library now,’ and their attitudes are changing because they’re able to compare before to now.

But we also have the little kids who are coming up through the grades now and will know from the very beginning that books are cool. That’s amazing to me.