Maura Hendrickson didn’t like peering over her elementary school students’ shoulders while they worked on desktop computers. Yet, with no other way to see their monitors, it was the best defense she had against a student getting distracted, falling behind, and doing poorly.

“The pain it takes [for students] to sit there and wait for someone to help can be [frustrating],” says Hendrickson, an integration specialist at Lincoln Elementary School in the 8,000-student Grand Island, Neb., school district. “You may have become disconnected with what you’re working on.”

But with Apple Remote Desktop, or ARD, the Grand Island district’s classroom-management software, Hendrickson can watch students work on lessons from her own machine, guide them through tough problems, distribute documents or software to multiple students’ hard drives, and show slides for lectures directly on their monitors.

“This is a very funky thing,” Hendrickson says. “It’s not just something you can imagine. It’s hard to believe one piece of software can control all those machines.”

As schools become increasingly dependent on computer labs and 1-to-1 computing approaches, more are enlisting ARD or similar software from competitors like Orem, Utah-based LanSchool or Calgary, Alberta-based SMART Technologies to help save time, money, and other resources.

Typically, the software allows teachers or administrators to take over multiple machines on a network at once and either operate them as if they were sitting at the keyboard or just peer in on the student’s use of the machine. The idea is to help teachers keep tabs on students in 1-to-1 computing environments, but more savvy instructors say the software is much more flexible than that.

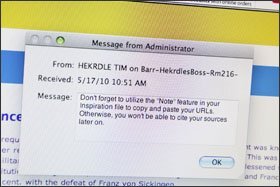

“I find new uses for it all the time,” says Kelley Ward, who teaches instructional technology at Barr Middle School in the Grand Island district and has utilized ARD to take inventory of technology hardware and documents for students who either don’t know how to open them, or don’t have access.

Benefits and Drawbacks

Yet with models for computer-based instruction evolving and concerns about online privacy growing, how best to incorporate classroom-management software into learning is open to debate.

Ted Lai, the director of technology and media services for the 13,600-student Fullerton school system in California, is among the technology experts who say overuse of classroom-management software can counteract the benefits of computer-based learning.

While 2,200 students at nine of the Fullerton district’s elementary and middle schools participate in a 1-to-1 program with school-issued Apple iBooks or MacBooks, Lai estimates only 5 percent of the teachers in 1-to-1 environments regularly use ARD. And while he praises teachers who use it to improve instruction, he cautions that using classroom-management software can feed a teacher’s instincts to remain at the center of the learning process, the so-called “sage on the stage” approach that good use of technology is supposed to counteract.

“I think that one of the biggest things [in using technology] is to differentiate learning as much as possible so that students are not just listening to lectures, but that students are directing learning and discoveries,” Lai says. “In our district, we haven’t pushed a system like this as much as we’ve pushed an environment where we can monitor in a different way.”

Lai encourages teachers to use ARD to display how students have successfully solved a problem during a lesson, but not to use it to replace face-to-face interactions.

At the 1,300-student Hemlock public schools in Michigan, technology coordinator Tom Lockwood is preparing to pilot a 1-to-1 computing program with special education and Title I students, though details of who is issued how many laptops or netbooks haven’t been finalized.

Lockwood says the LanSchool software the district uses is essential to help a small school system expand its technology profile. And in his district it is particularly useful for teachers who can use the software to lead students through calculations in high school accounting courses, or features of computer-aided design. He adds that it could also hold an appeal for districts wishing to conserve resources and teachers wishing to conserve energy.

“If you really need more than one teacher in the lab just to supervise what’s going on, you can’t afford the extra person, so it could save money,” says Lockwood. About keeping students off social-media sites, such as Facebook, and online games during class time, he adds: “If you’re dealing with kids in a lab environment, it can be a pain in the neck. There’s motivation to learn [to use the software].”

Beyond Keeping Tabs

Some technology directors concede that the public perception of classroom-management software is that it’s mainly used for spying on students. And some teachers have the tendency to note the restrictive benefits of the software before the instructive ones, which some experts see as a misguided perspective.

Kathy Moore, the media coordinator at Pine View Middle School in the 26,000-student Washington County district in southwestern Utah, praises LanSchool’ssoftware for letting her monitor what students do online when they visit the library at lunch, or before or after class.

“I think it does make them more productive. If they’re not, I very quickly know,” she says, adding how she has opened Internet windows students minimized on their own screens.

Michael Williams, the technology director and a former office-technology teacher in the 2,400-student Early County school system in Blakely, Ga., says that while he purchased SMART’s software to do some “very refined teaching,” educators in his district can and do use the system to monitor how students use the Internet.

Nebraska’s Grand Island system, however, is among the districts that actively discourage administrators and teachers from using software as a spying device without just cause.

“We are very, very clear with our technology-support people that they are not to be using [Apple Remote Desktop] to scan networks and monitor what people are doing,” says Sue Burch, the technology director at Grand Island schools. “There’s enough paranoia about Big Brother watching.”

Burch says a better strategy is to be aware of signs of network abuse, like slowed network speed or a student’s sagging performance, and then investigate the situation.

While teachers continue to explore appropriate use of classroom-management software in class, the biggest benefits may actually occur outside of class time. Such software can solve little logistical problems—such as retrieving group work from a classmate’s computer when he’s home sick—or bigger ones, like installing a virus update on several hundred netbooks in a few minutes.

“It’s the ability to administer a network without having to go room to room to room,” says Burch. “It’s the ability to sit on the couch in the evening and restart our servers or update our servers. It’s the ability when you’re out of town on a conference, and a teacher or administrator says something is not right, to see the desktops of users.”