One of three grants Linda Barton relies on to provide out-of-school programs to her students will run out this month.

With two other grants still in play, Ms. Barton is perhaps in a better situation than most such providers, but she’s trying to figure out how to maintain her existing programs in her Lander, Wyo., community until she can get more money.

“The funding is always a challenge,” she said.

Ms. Barton is the executive director of a K-12 before- and after-school program, Lights on in Lander, in the central part of the sparsely populated state. The school-based program is financed with public dollars and serves nearly 340 students.

Rural out-of-school programs such as those Ms. Barton runs face a host of challenges because of their isolated locations. Inadequate funding, access, transportation, and staffing are among the biggest obstacles.

Despite increasing national attention to the potential for out-of-school programs to enhance school offerings and provide academic enrichment, leaders in rural areas mostly agree that their troubles, exacerbated by the economic crisis of recent years, aren’t getting easier.

“Most programs that we surveyed are actually worse off than three years ago at the height of the recession,” said Jen Rinehart, the vice president of research and policy for the Afterschool Alliance, based in Washington.

Obstacles Identified

For after-school providers in rural communities, much like their urban counterparts, the economy is an ongoing challenge to their ability to provide high-quality programming to enough students, said Ms. Rinehart, citing recent studies.

“The indication is that rural communities seem to be right in line with the overall after-school picture, which is not optimistic,” she said.

A 2011 Harvard Family Research Project report found that out-of-school-time programs in rural areas had positive effects on students, but they face problems that urban and suburban programs did not.

The report, “Out-of-School Time Programs in Rural Areas,” highlighted high family poverty, low funding, lack of transportation, and a shortage of qualified workers as some of the biggest issues facing rural communities.

On funding, rural areas generally have smaller populations that limit financial resources. They receive less federal, state, and local money for after-school services compared with urban and suburban areas, according to the study.

Another report, “Uncertain Times 2012,” released this year by the Afterschool Alliance, found that nearly four out of 10 programs reported that their budgets were worse today than at the height of the recession in 2008.

That lack of money is huge for Sherry Comer, who has directed an after-school program in Camdenton, Mo., for 14 years. Her program was one of the original recipients of the federal 21st Century Community Learning Center grants, and it’s relied on a combination of sources, such as federal Title I and economic-stimulus money, to keep afloat since then.

“It is exhausting, and it takes a lot of my time to keep the balls juggled,” said Ms. Comer, who serves on the Missouri AfterSchool Network board. “It’s consistently been a challenge since we started. I’m always looking for where we can get funding.”

Out-of-School Enrichment

Many rural communities rely on 21st Century Community Learning Center grants to serve their students. The program offers funding for centers that provide academic-enrichment opportunities during nonschool hours for children, especially those who are considered poor and attend low-performing schools.

The $1.2 billion program is formula-based and allows states to decide how to distribute the money. There’s no mandate for a rural set-aside, although some states award grant applicants more priority points if they are rural.

An estimated 8.5 million children are in after-school programs nationwide, and more than 1.5 million are in those funded by that pot of federal money, according to the Afterschool Alliance.

Sylvia Lyles, the director for academic improvement and teacher-quality programs in the U.S. Department of Education’s office of elementary and secondary education, which oversees the 21st Century grants, has rural areas on her agenda because they face so many difficulties. She has worked closely with some states on solutions.

“From my vantage point, I don’t believe it’s getting harder [for rural schools],” she said. “I think it’s a hard issue.”

In some communities, the lack of money can lead to a lack of access, which is troubling for rural after-school advocates. One national study found that 57 percent of rural parents who said their children didn’t participate in after-school programs cited the unavailability of such programs, compared with 37 percent of suburban parents and 36 percent of urban parents.

Ms. Rinehart of the Afterschool Alliance pointed to data that show children in rural areas were the least likely of all geographic groups to take part in after-school programs because those programs didn’t exist where they lived. That was particularly true among low-income rural families, she said.

“Given the research that we have, perhaps there should be additional focus on rural communities because we know that kids in those communities are least likely to be able to access after-school programs,” Ms. Rinehart said.

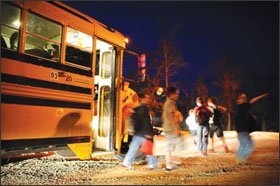

The isolation of rural communities can make transportation to and from out-of-school programs a costly and time-intensive prospect. Rural areas typically don’t have the public-transportation systems available in more-populated areas.

“It’s harder to keep the kids here and to get them home,” said Ms. Comer, the Missouri after-school provider. “Transportation is a huge barrier.”

Ms. Comer spends roughly 15 percent of her program’s budget on transportation, but that’s still not enough to be able to deliver students to their front doors. The program trimmed costs by creating drop-off points, and those work well until later in a given month, when parents run low on money, she said. When parents can’t afford the gas to get to work, much less pick up their child from a drop-off point, the child can’t stay after school, she said.

Finding the staff needed to run out-of-school programs can also be difficult. A smaller workforce, low education levels, and high poverty rates make it tough to recruit and retain employees.

In Wyoming, it’s hard to find employees who are willing to come in and work for two hours in the middle of the afternoon with no benefits, Ms. Barton of Lights on in Lander said.

Finding Success

It’s also hard to find money or time to offer additional training, and there’s no money set aside to provide for cost-of-living adjustments or raises, which Ms. Barton called a flaw in the federal 21st Century grant program.

“How do you run these programs effectively and meet the requirements that are becoming much more demanding in terms of expectations?” she said.

The international child-welfare organization Save the Children began its work in Appalachia about 75 years ago, so its roots are in rural communities. It started focusing more on after-school programs in 2005, which was when Ann Mintz designed a literacy-based program to build children’s skills outside of school.

What started in about 30 schools now has spread to 156 serving more than 19,000 students in 14 states. Save the Children targets high-poverty schools with a high percentage of struggling readers.

“We have found our niche to be rural, but the program we’ve designed would work anywhere,” Ms. Mintz said. “There wasn’t another entity that was coming into rural areas to provide out-of-school programs. If you look at cities, there are some fabulous out-of-school programs. We didn’t see any for rural areas.”

In some ways, she said it’s becoming easier to operate rural programs, but other issues have made it more difficult.

“Transportation just doesn’t get any better,” she said. “It probably gets worse with gas prices going up.”

Equipping staff members with the necessary tools and skills requires creativity and resourcefulness. Long-distance communication tools such as online video chats have made it easier to support those implementing on-site programs, but it’s been harder to provide the ongoing, face-to-face training that’s needed, Ms. Mintz said.

“There’s no replacement for face-to-face time,” she said.

Despite the problems, after-school programs have become embedded in many Wyoming communities, which have come to rely on and expect them, said Ms. Barton, who is also the executive director of the Wyoming Afterschool Alliance. Still, rural programs struggle to follow the best practices of national programs and policy models that often don’t translate well in their communities, she said.

Localized Application

She described her home state as an example. National out-of-school advocacy groups have suggested scheduling meetings with mayors’ policy aides, but that is out of touch with what goes on in Wyoming, she said.

Local officials often serve in those roles part time, and they don’t have a staff. The same is true for state lawmakers, who don’t even have offices.

“I think that people don’t really understand the definition of rural in the same way,” Ms. Barton said.

Many rural programs have come to rely on statewide after-school networks in 41 states that are committed to helping ensure children have access to high-quality after-school care, Ms. Rinehart said.

“Those have really taken on the challenges with rural communities,” she said, adding that they’ve tried to create infrastructure to link rural programs.

Ms. Comer agreed, saying Missouri’s statewide network has helped her programs be successful.

“You have a cohesive system that helps you sustain,” she said. “It’s not easy, and it’s work.”