New York City’s ban on cellphones in public schools is 18 years old, but a recent step-up in enforcement has caught thousands of the mobile devices in its dragnet, sparking outrage among families who consider the phones a lifeline.

The mayor and the schools chancellor argue that cellphones can’t be allowed on school property because they cause a range of problems that distract students from learning. They cite nearly 2,500 disruptive cellphone incidents during this past school year—and that doesn’t count the 3,000-plus phones collected at school doorways in an April-to-June crackdown.

Local civil rights groups and city and state lawmakers are mobilizing to file lawsuits or pass legislation loosening the ban, one of the strictest in the country. Among the nation’s largest districts, only two others—Detroit and Philadelphia—prohibit student cellphones on school property. Most allow students to bring them, but require them to be turned off during instructional hours.

The clash in the 1.1 million-student district echoes dilemmas faced by educators nationwide as a rising proportion of teenagers—from nearly half to almost two-thirds, by varying research estimates—now have cellphones.

Legal experts say that challenges to New York City’s ban could set new guideposts for school cellphone policies, since most previous cases have disputed disciplinary actions arising from inappropriate use, rather than the policies themselves.

The devices have proved troublesome in many U.S. schools, where students have used them to chat with friends during class and cheat during tests by using mobile Web capabilities. But families increasingly see them as an important way to stay in touch with students, whether they are on isolated country lanes, in suburban shopping malls, or in crowded subways.

Many states banned portable communications devices, such as beepers, from school in the 1980s, seeing them as tools of the drug trade. But after the 1999 shootings at Colorado’s Columbine High School, many states dissolved those prohibitions, allowing districts to decide whether students could bring or use cellphones.

Opponents of the New York City rule contend that by barring cellphones at school, the 1988 regulation improperly encroaches on the before- and after-school time when families most want their children to have mobile phones to use if they are lost, in trouble, or need to change plans.

‘I Need These Phones’

The initiative that Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and Schools Chancellor Joel I. Klein announced in April was meant to snag weapons in schools. Only 80 of the city’s 1,400 schools are equipped with metal detectors, so mobile scanning devices began paying unannounced visits at other schools to detect weapons. Letters were sent to parents warning of the impending searches and reminding them that district policy barred cellphones at school, said district spokesman Keith Kalb.

Between April and June, 3,027 cellphones and 36 weapons were confiscated. The phones were later returned.

Donna Lieberman, the executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, objects to the “overpolicing of schools” that takes shape when safety officers employed by the city police department are used to enforce a school district regulation. The latest round of searches has prompted dozens of complaints, she said, including “inappropriate pat-downs” by opposite-sex officers and a case of a teenage girl who had to lift her shirt when her underwire bra set off the metal detector.

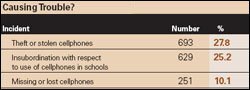

The New York City Department of Education, which bans student cellphones in schools, reported the following cellphone-related incidents for the 2005-06 school year, through June 8.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: New York City Department of Education

Students should be held accountable for improper cellphone use in school, many New York parents say, but should not be barred from carrying them to use before and after school. In a city where it is common for students to commute an hour each way to school on public transportation—and particularly since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001—cellphone connections are necessary, they argue.

“This is absolutely, 100 percent a safety issue. It’s for peace of mind,” said Beth G. Kneller, whose son will walk a mile and a half through a Brooklyn neighborhood to attend 6th grade in the fall.

Carmen Colón, a single mother whose three sons attend school in two different boroughs, said the phones are a lifeline for crucial logistics as she juggles everyone’s schedules.

“How about when the 4 [train] stops running and my 17-year-old can’t meet up with my 13-year-old, and therefore they can’t pick up the 10-year-old?” she said. “I need these phones. I‘m not waiting for a tragedy to happen.”

Juan Antigua, who just finished his junior year at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, said he can’t abide the choices the ban forces on teenagers. The 16-year-old had always complied with the rule, but one day took his cellphone to school because of an unfolding family emergency. Confronted with having to surrender it at the door, he turned around and cut school for the day.

“We shouldn’t have to decide between family and school,” he said.

Norman Siegel, a private New York City civil rights lawyer who is preparing a lawsuit challenging the ban, said the city is obligated to explore less-intrusive possibilities, such as disciplining students for improper phone use, or collecting all cellphones and holding them for the day.

Drain on Schools’ Time

But some who work in the city’s schools laugh off such solutions as unworkable. The only way to manage cellphone disruptions, they say, is to keep them from coming through the door.

“Get lockers? Are you kidding?” said Grace Zwillenberg, the principal of John Adams High School in Queens. “Can you imagine 3,500 kids putting cellphones in a locker? Then 3,500 kids getting them out at the end of the day? You’d have to assign personnel to handle that. And that takes away from my instructional budget.

“If you leave it to teachers to handle a cellphone going off in class,” she continued, “then you have them in confrontations with students, and that takes away instructional time.”

Marc Epstein, the dean of students at Jamaica High School in Queens, said cellphones account for a huge proportion of his student-discipline problems. In 2004, he confiscated a cellphone from a student outside his office, he said, only to be jumped from behind by a student who contended that it belonged to him. His school used to collect all phones daily, but abandoned that practice, he said, when “we didn’t have enough room in our safe.”

Dennis M. Walcott, New York’s deputy mayor for policy, said the city intends to stay the course in enforcing the ban. He said members of “a silent majority” of parents and teachers approach him often and urge him to stick with it, seeing cellphones as a distraction in class, and noting that they got along fine without them when they were young.

“We understand what the parents are saying [about] to and from school, but [our concern is] about what takes place in the school building itself,” Mr. Walcott said. “We’re very clear that the policy that’s in place will [remain] in place.”

Thomas Hutton, a staff lawyer for the National School Boards Association in Alexandria, Va., said districts face a daunting task in trying to keep cellphones at bay.

“With the technology so ubiquitous,” he said, “it’s getting harder and harder to ban them altogether.”

Combine the popularity of the technology with powerful dynamics of teenage culture, and cellphones are even tougher to manage in school, observers say.

Scott W. Campbell, who studies the social implications of new media as an assistant professor of communication at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said cellphones give teenagers yet another way to do what they’ve always done: build their identity through social ties to their peers.

“They can’t help themselves,” he said. “They’re ‘texting’ each other beneath the desk in class. They just have to keep those connections to each other.”

Cellphones also enable teenage independence in ways that particularly rankle adults, Mr. Campbell said.

“The mobile phone is a symbol of autonomy,” he said. “It lets you carry out your life under the radar screen of authority. It empowers you to do and say what you want, with whomever you want, whenever you want.”