Corrected: An earlier version of this story had an incorrect start date for the documented decline in the number of high-dropout high schools. The report traces the decline from 2002.

After decades of flat-lining graduation rates, states finally have started to turn around or close hundreds of so-called “dropout factory” schools and recover some of the thousands of students who had already given up, according to a new study.

The Washington, D.C.-based policy firm Civic Enterprises, whose 2006 report, “The Silent Epidemic,” helped galvanize state and federal attention on high school dropouts, reported Tuesday that most states have gained momentum in improving graduation rates, but will need to improve at least five times faster to meet a national goal of 90 percent of students graduating on time by 2020.

The study suggests that a combination of state economic concerns and federal accountability pressure has helped drive up the national graduation rate from 72 percent in 2001 to 75 percent in 2008, the most recent federal graduation estimate. Black, Hispanic, and Native American students made some of the greatest gains, but more than 40 percent of those students still did not graduate on time as of 2008.

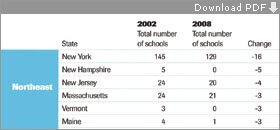

It also finds that the number of high schools that graduate 60 percent or fewer of their incoming 9th graders four years later—the so-called “dropout factories,” which account for fully half of the students who leave school each year—has declined from 2,007 schools in 2002 to 1,746 in 2008.

Regular and vocational high schools with more than 300 students whose first class entered no later than 2004-05.

SOURCE: “Building a Grad Nation”

In the report, the study’s authors—John M. Bridgeland, the chief executive officer of Civic Enterprises; Laura A. Moore, the organization’s program and policy manager for youth development; Director Robert Balfanz and Deputy Director Joanna H. Fox of the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore; and the America’s Promise Alliance, a Washington group started by former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell—call for a “Civic Marshall Plan” to reconstruct the nation’s high schools as comprehensively as the Allies planned to rebuild Europe after World War II.

The plan advises all states to follow the best practices of states such as Tennessee, which had a 15 percent graduation-rate increase, and New York, where the numbers of students graduating on time rose by 10 percent over the 2001-2008 study period.

These include targeting schools with high dropout rates and the lower grades that feed into them; providing more-rigorous course requirements along with more flexible class schedules for students; and developing early-warning systems to identify students in earlier grades at risk of dropping out, among other strategies. It also tailors specific strategies for each state to enable them to reach the 90 percent graduation goal.

“Most states did one or two or three things together, but it’s the places that weave multiple things together that made the biggest progress,” Mr. Bridgeland said, “It’s not just saying, ‘Do it better,’ but saying, ‘We can help you do a more comprehensive approach to get bigger impacts.’ ”

Mr. Bridgeland said there is greater political will to increase graduation rates now, both because the economic crisis has increased concern about global job competitiveness and because 2008 changes to federal education grants require that states and districts report graduation rates using a uniform longitudinal measure that tracks individual students from 8th grade through graduation.

“I would just tell you the phones are ringing off the hook from states and districts that are waking up to the fact that they have to meet these graduation-rate-reporting requirements and annual targets for AYP,” Mr. Bridgeland said. The latter reference is to the federal No Child Left Behind law’s mandate for schools to make “adequate yearly progress” on state tests and other measures each year.

The new measure, called the adjusted cohort-graduation rate, must be reported beginning in the 2010-11 school year, and states and districts will be accountable for meeting annual improvement targets using the measure beginning in 2011-12. “It’s not just accountability, but the requirement that everyone calculates the graduation rate in the same way; it’s similar to what the [National Assessment of Educational Progress] does in leveling the playing field,” Ms. Fox said. “You can’t pull the wool over anybody’s eyes anymore by saying, ‘We have a 90 percent grad rate’ when you have schools that have a 50 percent graduation rate.”

For this study, however, researchers used existing U.S. Department of Education estimates for calculating cohort graduation rates for states and the nation as a whole.

Overhauling ‘Dropout Factories’

The 261-school decline in the numbers of high schools classified as “dropout factories,” drawn from data gathered by the Everyone Graduates Center, doesn’t tell the whole story. Seven hundred new schools were identified during that time even as 900 previously identified schools turned themselves around. Southern states made the most progress, accounting for 216 of the schools that improved enough to get off the list.

“The South has been very poor for very long, and Southern governors have seen education as a real economic imperative,” said Ms. Fox of the Everyone Graduates Center. The turned-around schools in that region seemed to have more “stick-to-itiveness” than those where dropout rates remained low, she said. “They kept trying different things. If something didn’t work, they modified it again.”

For example, Mr. Bridgeland and Ms. Fox attributed Tennessee’s improvement to comprehensive reforms, such as training and distributing 100 “exemplary educators” to coach and lead instruction in high-need high schools while toughening graduation content requirements and conducting school-by-school monitoring and improvement plans for the worst high schools. The state even required students under 18 to attend school or graduate in order to get a driver’s license.

While some education watchers have voiced concern that increasing education standards could make it harder for students falling behind in high school to catch up and graduate, Mr. Balfanz said the research showed “the exact opposite: Increasing their standards and requirements improved graduation rates. It’s exactly what the dropouts had said they wanted: more rigor; to be challenged.”

Recovering Students

Alabama, another state that succeeded in raising school completion rates, based its graduation initiatives on a series of surveys of students who had already dropped out of the system, according to Tommy Bice, the state’s deputy superintendent of education. “For years, we had attempted to re-engage students in school, but we were attempting to re-engage them in a system that hadn’t worked to start with,” he said. “I think the reason we’ve been able to make some significant moves is we’ve started listening to our students. We started seeing things that were policy driven that, if changed, would make it easier for students to come back.”

The state ramped up its graduation requirements but based mastery on skills tests rather than Carnegie units of credit or seat time. It also expanded credit-recovery programs to provide more support for students. The Mobile school district, for example, has re-enrolled more than 500 students who had left school in the past year through “drop-back-in academies” set up in neighborhood centers and empty storefronts. These allowed students to schedule their own school hours around work and family care, Mr. Bice said.

This school year, the state also plans to join Louisiana and South Carolina in launching a statewide longitudinal student data systems that can flag predictors of dropout risk in elementary school. These early indicators include absenteeism, behavior problems, and failing core classes, such as mathematics and reading.

Such systems are critical, Mr. Bridgeland said, because even the more-accurate graduation rate methods come too late, rendering them “basically autopsy reports on these students.”

Individual schools already are using such early-warning systems as part of their turnaround plans. The Feltonville School of Arts and Sciences, a middle school that has been a feeder for high-risk high schools in Philadelphia, implemented a student-tracking system as part of the Diplomas Now initiative piloted by Mr. Balfanz.

The system allowed teachers to identify and target students with recurring absences or academic or behavior problems, all of which have been found to predict high school dropout risk. The school partnered with community groups, such as City Year and Communities in Schools, to provide additional help to those students. Within a year, the number of students failing core subjects dropped by 80 percent in reading and 83 percent in math; the number of students missing 20 percent of class or more dropped by more than half. Diplomas Now has since received a federal Investing in Innovation grant to replicate the program in other high-dropout schools and their feeder schools.

“We think these (early warning systems) can be a big additional lever to mobilize resources to help these students,” Mr. Bridgeland said.