As states begin receiving results from assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards, international education consultant and former OECD analyst Vanessa Shadoian-Gersing takes a look at the Common Core’s global roots as well as their goal of promoting the 21st century skills that high-performing education systems around the world are also working to incorporate.

This fall, for the first time, many states will receive results from assessments aligned with the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), making this an opportune time to pause and recall why states started down this path.

Goals and Global Roots of the Common Core State Standards

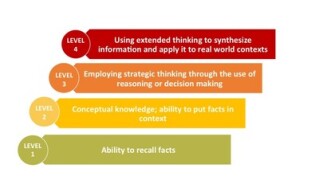

The evolving nature of work and society puts a premium on students’ ability to transfer what they learn to address new challenges. The CCSS were designed to dramatically shift learning from passive intake to the deep content knowledge and critical thinking required to succeed in the 21st century. This focus is shared by high-performing school systems—in Asia and beyond—which are embracing complex skills and higher-order thinking in their 21st century skills frameworks.

The best school systems create high, consistent expectations for all students’ learning, so the CCSS prioritize focus, rigor, and coherence. This is a considerable upgrade from many states’ earlier standards, which covered too many topics, were repetitive across grades, and left many students behind their global counterparts.

As states operationalize these ambitious goals, they need effective ways to monitor learning. Leading global school systems recognize that certain types of assessments authentically capture higher-order skills. Similarly, the new standards shift the focus toward next-generation assessments of deeper learning, and two state consortia were tasked with developing such tests for 2014-2015.

Sobering Test Scores

As first-round results trickle in, they point to the work ahead. Predictably, scores are generally lower than on previous (albeit incomparable) exams.

For example, in populous, diverse California, Smarter Balanced assessment results show that 44 percent of test-takers met or exceeded the new bar for proficiency in English/language arts (ELA), and 33 percent did so in math. More than one-quarter “nearly met” the standard in ELA as well as in math.

The state scores also reveal stark achievement gaps: 31 percent of economically disadvantaged students achieved proficiency in ELA, while 21 percent did so in math. Between ethnic groups, 72 percent of Asian and 51 percent of Caucasian students versus 32 percent of Latino and 28 percent of African American students met targets in ELA. Among the state’s many English-learners, 11 percent achieved proficiency in both ELA and math.

Officials expected achievement gaps to widen initially due to both technology demands and harder, unfamiliar content. While technology access issues may have contributed, particularly among lower-income students, scores indicate that many students need to make more progress. California Superintendent Tom Torlakson rightly considers the scores a baseline from which to gauge future progress.

Making Results Meaningful

Indeed these scores reflect, in part, the rigor of the new standards as well as the focus on assessing critical skills, which take time and effort to master. But what can we learn from them in the meantime? Careful interpretation can help schools and districts use this data wisely to inform improvement.

Ambitious New Assessments

The new assessments better represent what students know and can do than did past exams and can better inform classroom instruction. Still, no single test can measure everything, and California is crafting a new approach linking scores with such indicators as college success and school climate.

Advances in Performance Assessment and Technology

Capturing meaningful learning outcomes is a complex endeavor, especially on large-scale summative exams. The US has trailed other nations investing in assessing higher-order thinking, and the new tests embrace performance assessment, an authentic way of gauging mastery, at an unprecedented scale. Students now analyze and explain their reasoning, a clear contrast to the lower-level skills No Child Left Behind-era tests tended to measure.

The tests also feature technological advances. In 2014-2015, most students took computer-based rather than paper-based exams. And the Smarter Balanced test adapts to each student’s skill level to generate better information about strengths and weaknesses. Though technology demands may have affected first-round scores, experts anticipate the new design will reduce performance obstacles and ultimately help level the playing field.

Room for Development

While the tests embody principles of high-quality, next-generation assessment, some consider these advances a first step toward the original goals. Both consortia proposed systems pairing extended, performance-based tasks with traditional items and companion materials to help translate year-end targets into instructional units. Yet, political, technical, and financial constraints required scaling back the complexity of some items, and the development of classroom tools lagged behind the year-end tests that generate school ratings. The first roll-out surfaced other areas that need adjusting, including test length.

Family and Community Factors

Out-of-school factors affect learning, and interpreting scores requires nuanced understanding of such factors. With specific demographic information, schools and districts can better ensure that students’ strengths are maximized and needs are met.

The nearly 5 million English Language Learners (ELLs) nationwide and in states like California are a noteworthy example. To help schools meet this diverse group’s needs, the Department of Education created a tool kit for high-quality education provision. Stanford’s Understanding Language initiative is developing open-source materials to help educators working with ELLs navigate the common standards’ specific language complexities.

Preparation to Teach Common Core Content

Rigorous standards and assessments are not enough to improve learning. Successful implementation will require equipping educators for the CCSS’s specific demands to deepen their content mastery, choose or create aligned instructional materials, and broaden their pedagogical repertoire.

Educators need to deeply understand the standards if students are to master them—and research suggests that teachers need support in learning and applying these new demands. Examples from other countries show that doing so at scale requires robust and sustained forms of professional learning. And a new approach to professional learning—that fosters collaboration and continuous improvement—is what most teachers say they want.

Some states and school systems prioritize such support, creating robust learning opportunities and tools for classroom use. Case studies from New York, Sacramento City, and Washoe County (Nevada) showcase different approaches to the sort of high-quality professional learning that helps teachers succeed.

Instructional Leadership Capacity

In most high-performing countries, a central curriculum and strongly-aligned instructional materials accompany their standards to support implementation. Without such guidance in the US context, local instructional leadership becomes even more important. To effectively lead implementation, principals and district leaders also need a deep understanding of the standards and instructional shifts, practice in recognizing these in classrooms, and support for ongoing capacity building.

Looking Ahead

As the recently, and soon-to-be, released scores around the US demonstrate, much work remains to ensure proper implementation of the CCSS and aligned assessments. But as our schools increase the rigor of their curriculum and further align with 21st century skills, we will begin to see achievement gaps narrow. All students should graduate prepared for work and life in the 21st century, and the CCSS has the potential to help them do just that.

Connect with Vanessa and Heather on Twitter.

Image credit 1: DrAfter123/iStockPhoto

Image 2: Depth of Knowledge Levels, courtesy of the author.