For months, teachers have been asking how teaching in person this school year is really going to work: How will they speak loudly enough for kids to hear them through a mask? How can they develop community in a socially distanced classroom? Is teaching outside even possible?

But now, the school year is here, and teachers who are back in school buildings are figuring it out in real time, devising ways to make new restrictions manageable for themselves and their students. According to Education Week’s database of more than 800 districts, which is not nationally representative, more than half have opened school doors for at least some in-person instruction.

Of course, innovation and creativity don’t get rid of the very real worries that many teachers are still facing at the start of this year. Some are figuring out where they’ll find care for their own children as they head back into school buildings, while others at higher risk of complications from the virus are deciding whether to go back at all.

Facing this uncertainty is taking a mental toll. According to data from the Education Week Research Center, teacher morale is at its lowest point since the beginning of the pandemic.

Still, teachers who are headed back into the classroom have said they’re doing their best to adapt to the situation at hand. They’re turning to colleagues and professional networks to crowdsource, brainstorm, and field-test new solutions.

“If you’re feeling helpless, reach out,” said Becky Schnekser, a K-5 science teacher in Virginia Beach, Va. “Rely on others.”

Education Week spoke with five teachers about how they’re adjusting to in-person classes.

Managing Mask Fatigue

Nearly 90 percent of district leaders say they are requiring employees to wear face coverings in school, according to a recent nationally representative EdWeek survey. For teachers, it’s a necessary safety precaution that has created a range of logistical problems.

Kelly Borrowman, a high school science teacher at a private boarding school in central Florida, said teaching in a mask has been a big adjustment. Her mask was growing increasingly damp over the course of the day. She wasn’t drinking water. Her throat was dry, and her voice was strained, since she was trying to make sure her students (both in the classroom and those watching her from a livestream at home) could hear her. She was trying not to move her jaw too much so the mask wouldn’t slip, which meant her jaw ached at the end of the day.

“I just wasn’t feeling good,” she said of the first couple of days on campus. “I could tell I was dehydrated.”

Now, Borrowman’s made a few simple adjustments that have eased the transition to all-day mask-wearing. She brings two masks a day—one for the morning and one for the afternoon, which helps keep them dry and clean. She also makes sure to take plenty of breaks to get water—which she does by stepping outside her classroom, to avoid taking her mask down in front of students.

She has also invested in multiple comfortable masks that make a statement. Borrowman, who teaches marine science, has some shark-patterned masks that are made from plastic debris that was collected from the ocean. The material is lighter, she said, so her face isn’t sweating. She also has some masks from the University of Illinois—where she’s currently earning a graduate degree—to inspire her high school seniors.

Adjusting to wearing masks is just one of the ways that this year has so far been unlike any other, she said.

“I think it’s best for teachers to recognize it is a lot,” Borrowman said. “Everybody is in their first year of teaching. We’re going to make mistakes, and we have to be OK with that.”

Projecting a ‘Teacher Voice’ From Behind a Mask

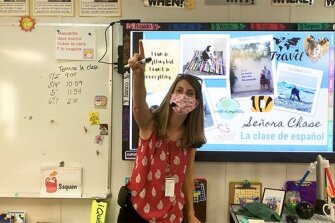

Like Borrowman, high school Spanish teacher AnneMarie Chase anticipated that she would have trouble talking loudly enough, all day, with a mask on.

In the weeks before school started, she remembers clear masks being a hot topic of conversation in online teacher forums. The big question was how to make sure that kids could see a teacher’s mouth move. “I thought, maybe it’s more important that they can hear me clearly,” said Chase, who teaches in the Douglas County school district in Minden, Nev.

Searching around for solutions, she remembered something from years ago. “My mom was an elementary school teacher forever, and in her school district, which is not where I teach, they did microphones in all the elementary schools ... just kind of to level the playing field for students with disabilities and English-language learners.”

So Chase bought a portable voice amplifier: a headset microphone that projects out of a small speaker she can attach to her belt.

Chase wears the microphone over her mask when she teaches. (Don’t put it under, she advises: “You can hear yourself breathing like Darth Vader, and it’s really scary.”) It’s harder to get the breath she needs to project her voice while she’s wearing the mask, Chase said. “I’ve found with the microphone that I don’t have to project, I can just use my normal voice.” Her speech is also clearer in the videos of her teaching that she records and uploads for students learning remotely.

Now that she’s been in the classroom for a few weeks, Chase is feeling more confident than she was in the lead-up to the first day.

“The worst was waiting for school to start,” she said. But “the first and the second day, I was like—I can still do what I do.”

Connecting Without Hugs or High-Fives

Kindergartners want to be close to their teachers and their classmates. But in a socially distanced classroom, that’s not possible—and that’s a hard pill to swallow for both parents and teachers.

“Unfortunately, we have to put our hands out and say, ‘We can’t hug,’” said Michelle Clark, a special education teacher in Virginia who’s co-teaching in a kindergarten classroom.

Her solution: cardboard high-fives. Everyone in the classroom has a cardboard hand that they decorate how they want. Each hand is glued to a stick so students can high-five each other—and their teachers—from a safe distance, without making contact.

Worried that students will experience emotional trauma in a social distancing classroom? In my experience (3 days), it’s what you make of it. If you make it a positive experience the students will embrace it. Here, a student wanted to create a handshake with our cardboard hands. pic.twitter.com/Q6v6Ysd8LF

-- Cardboard High-Five Teacher (@M_P_Clark11) July 2, 2020

(When Clark taught 2nd grade this summer school, the students traced their own hands into the cardboard, so it was “truly their own hand,” she said.)

Right now, two groups of students are coming to school on alternating schedules in order to create more room in the classroom. But starting Sept. 14, all of Clark’s students will be there full-time. In order to ease the transition, she has printed out photos of all her students and glued them to their desks.

That way, “they’re going to know what that person looks like,” she said. “Once we’re able to be together as one big, happy family, it’ll be familiar.”

Another big challenge: To help facilitate contact tracing, students stay in their classroom all day, except for a 30-minute recess. They eat lunch in their classroom, and instead of going to specials like art class or the library, those teachers come to them.

“Those poor babies are in the classroom all day long,” Clark said. “They are antsy, so it’s really up to us to make it fun and interactive.”

Clark and her co-teacher have built in a lot of “mini brain breaks” throughout the day that get students moving. For example, the children will sing “Wheels on the Bus,” but instead of hand movements, they’ll jump up and down or run around their chairs. Read-alouds are now interactive, with a lot of moving around. And students go on “sensory paths” in the hallway, where they can zig zag, hopscotch, and jump.

Overall, Clark said her students have adapted well to a socially distanced classroom. They wear their masks without complaint, they wash their hands while cheerfully singing “Happy Birthday,” and they follow the rules to not touch anyone else or their belongings.

“I’m way more exhausted at the end of the day, but it’s all worth it,” she said.

Staying Organized in an Outdoor Classroom

Elementary science teacher Becky Schnekser said her school offered two choices for how she would teach this year in a socially distanced environment: livestreaming into homerooms, or by pushing a cart from classroom to classroom. Schnekser countered with “option C": Could she teach all her classes outside?

Her administration at Cape Henry Collegiate, a private school in Virginia Beach, Va., gave her the green light. But on the first day of school, Schnekser had trouble keeping track of the materials and personal items—water bottle, her walkie talkie—that she needed with her. “When [I’m] outside, I can’t just run to my desk,” she said.

She wanted to figure out a way to keep everything on her person. She thought of the aprons that she’d seen some elementary art teachers wear but decided they didn’t quite fit her style.

“I was like, you know what? Toolbelt. I’m teaching outside, it needs to be rugged, I need to have my hands free to dig in the dirt or look in a microscope or whatever I need to do ... it’s kind of like a walking desk,” she said.

Today, I wore a tool belt to carry the multitude of things that I need at arms length while teaching outdoors and it was magical. If you teach outdoors, especially science, and aren’t using a tool belt; go do it now-life changer. #expeditionschnekser #outdoored #disruptingscience pic.twitter.com/XZhCHosVfS

-- Becky Schnekser (@schnekser) August 28, 2020

The belt holds Schnekser’s open-air classroom essentials, including tape measure, screwdriver, pens, extra mask, hand sanitizer, seeds and gardening gloves, and sunscreen. She keeps duck and turkey calls in there, too, to gather students back to the main seating area.

The set-up has made logistics in the outdoor space easier for Schnekser, but she thinks it’s also had benefits for students’ motivation. Seeing their teacher out with her field gear makes the kids feel like they’re real scientists, she said.

In planning for this unusual year, Schnekser’s tried to focus on what still is possible, rather than on all of the new restrictions she’ll have to deal with. “We still can have fun, and we still can laugh, and we still can get up and move. It’s just going to look different,” she said.

Building Community Between In-Person and At-Home Learners

Many schools are opening with some version of a hybrid schedule that requires teachers to teach students in the building and at home at the same time. For those teachers, managing what’s going on outside of the room can be one of the biggest challenges.

This is the case for Jessica Salfia, an English teacher at Spring Mills High School in Martinsburg, W. Va. Salfia says her administration has tried to split up responsibilities so that some teachers are working with online students and some are working in person, but that’s not possible for her—she’s the only teacher for Advanced Placement Language and Composition and creative writing. School leaders are trying their best, she said, but still: “The schedule is bonkers. It’s unlike anything I’ve had to deal with as an educator.”

Planning for the start of the year, Salfia’s biggest question was how to create community between students in different locations. The first step had to be getting her mind wrapped around the schedule for the first few days. She could figure out when different groups would be learning at the same time and how she could help students build relationships in those windows.

Salfia made the schedule a visual anchor in her classroom, so she and students can see which classes are at home and which are online at any given time. She charted out how those periods would overlap.

Me trying to Beautiful Mind my COVID school lesson planning for both in person and digital instruction.

-- Jessica Salfia (@jessica_salfia) August 28, 2020

Building community is Salfia’s top priority for the start of the year. She’s been asking her 13-year-old daughter, who has formed friendships over social media platforms like Snapchat, for advice on how to encourage relationship-building. Her daughter’s answer? “We act like we’re in the same room together.”

Which is why Salfia is so focused on capturing and planning for the moments when students in different physical spaces will be engaged at the same time. “It’s ultimately so that we can create a classroom community once we’re together,” she said.

From top to bottom, photos courtesy of Kelly Borrowman, AnneMarie Chase, and Michelle Clark.