On assignment for Education Week, photographer Justin Cook reflects on his return to his familial roots as he documented two North Carolina school districts that benefited from the Obama administration’s education improvement agenda, and now face dwindling federal funds.

I knew High Point, North Carolina, because my dad was born there, and my grandmother told me lots of stories about growing up on Montlieu Avenue. I worked in a camera store on Main Street one summer in college. I went to high school down the road in Greensboro, so an assignment in Guilford county schools was like going home. But photographing at Parkview Expressive Arts Magnet School was like working at the center of my being: I’m a product of an arts magnet elementary in Montgomery, Ala. Without that experience, who knows where I would be today. I doubt I’d be shooting photos for Education Week.

The mood I set out to capture was “uncertainty.” What will happen to all the progress when some of the federal funds, specifically from President Obama’s Race to the Top initiative, dry up? Especially in North Carolina’s Title I schools, with the highest percentages of students from low-income families? Especially in a state where teachers have some of the lowest pay in the nation?

I arrived in High Point on a Sunday afternoon, checked into my hotel, and immediately drove to the school. I wanted to walk the neighborhood and make some landscape images. It was about 6:45 p.m. and the sky was dark with thunderclouds to the west. The sun sets after 8:30 p.m. this time of year, and the light was only getting better. There, in the school parking lot, was the vista I sought: A thunderhead towered in a white plume beyond the school, its base churning black ready to burst. I made some frames, then hurried down the street to the park that overlooked the school for a better view. A family with two little kids passed me on the sidewalk. “Mister, you better get inside, it’s about to rain,” a little boy hollered. A cold wind rushed over the hill. The cloud broke in the distance before it could reach us.

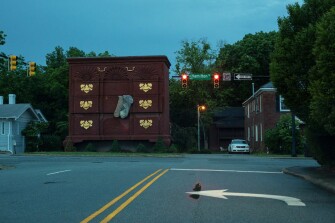

I returned to my car and drove downtown in the drizzle to capture more landscapes. High Point’s center is lined with quaint shops, restaurants, a theater, and posh furniture-showcase buildings. Economic diversification has helped High Point survive the outsourcing of the furniture industry that is still central to its economy. But if you drive less than a mile from downtown, it’s clear the investment hasn’t reached everyone. Five-year estimates from the American Community Survey 2013 show that 21 percent of High Point’s 103,000 people live in poverty, and 32 percent of children under 18 live in poverty.

On Monday, I found that 5th grade math teacher Virginia Stanfield and her colleagues at Parkview seemed undeterred, and even driven by these circumstances. She’s raised her students’ test scores faster and higher than other teachers, and won a $20,000 bonus from the Teacher Incentive Fund. She has reinvested most of that money into the classroom, buying supplies, prizes, food, and even clothes for students.

Federal grants have also equipped each of her 5th graders with tablets, which they use with many lessons. Stanfield says the arts programs offer her students new experiences and build confidence, and the real secrets to their success are the smaller class sizes (15 students), after-school tutoring, and personalized instruction afforded by the grants. Stanfield also reaches beyond the school walls and develops relationships with parents. Her students were focused, polite, and funny as she taught them how to develop a business plan to sell lemonade: Math through entrepreneurship.

The next day, I drove about an hour from High Point and found that teachers at East Iredell Elementary in Statesville have become students themselves, of data. Three times a year, they collect academic performance data, and fill yellow folders with personalized instruction plans for each student. They hone in on where students perform below grade level, and adjust their curriculum accordingly. Intervention specialist Vikki Stevens and instructional facilitator Janna Sells help lead the charge with a battlefield sense of purpose. Their conference room looks more like a war room: the walls are plastered with giant sheets of paper, marker-scribbled with year-by-year data analysis, color-coded progress charts, and intervention strategies – their plans in a long slog to “save students.”

I photographed them as they met with teachers from several grade levels, and celebrated a successful school year. According to their numbers, 458 students at East Iredell performed below grade level at the beginning of the 2013-2014 school year, but by the end of the 2014-2015 school year that number dropped to 168. The staff seemed at once exhilarated and exhausted by their efforts.

But the federal i3 grant that funds Stevens’ role at the school ends June 30th, and so does her job. She’s currently looking to see if she can stay at the school in another role, or move to another district that employs intervention specialists. In Statesville and High Point it was clear that while computing devices and technology may equip our kids for the times, old-fashioned relationships and intervention win their future.