Stress, alienation, substance abuse, a lack of belonging, pressure from high expectations.

Those are among the problems a group of high school student leaders say they’re ready to tackle head-on. But they aren’t just naming the issues; they’re also coming up with solutions to take to their peers and principals.

The pandemic has severely affected youth mental health, and school and district administrators often cite students’ well-being as a major concern as they strive for normalcy. But too often, students aren’t asked for their ideas on how to confront the challenges. And they have lots of ideas: mental health days for students and faculty, student-led professional development for teachers, hiring more women as school leaders, sessions on coping skills, promoting mindfulness and self-care, and providing on-campus quiet rooms and private spaces for students.

A mental health summit called by the National Association of Secondary School Principals earlier this month aims to change the dynamic that excludes students entirely or includes them only superficially in problem solving. The organization brought together nearly 50 students to the summit in Arlington, Va., along with adult advisers from their schools to brainstorm solutions.

‘Stressed out’ and ‘overworked’

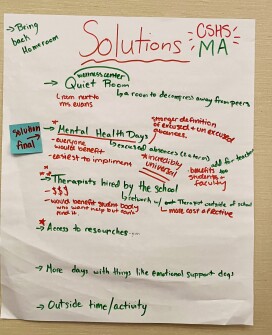

During the summit, El O’Neill and Nicole Sanchez’s team from Cardinal Spellman High School, a Roman Catholic school in Brockton, Mass., identified stress as the major problem they’d like to zero in on.

“It was easy to see that, across the board, our school is very stressed out and we’re overworked,” O’Neill, a junior, said. “This is how we see it and feel it.”

The group and their two adult advisers batted around a few ideas: a quiet room for students to decompress; mental health days for students and staff; additional therapists; more time and activities outside the classroom.

They settled on mental health days, in part, because it was universal and easiest to implement of all the options they’d considered. Hiring therapists costs money.

“We just kind of have the idea of students and faculty members taking a day that they feel is necessary for them is extremely important in order for them to keep succeeding academically and not only that, but mentally,” Sanchez said.

Joint PD with teachers to address discipline

Students from Oskaloosa High School in rural Oskaloosa, Iowa, chose discipline and disrespect as the problem they’d like to address.

Ava Ridenour, 15, a member of the school’s student council, said altercations and fights have increased in school and at after-school events during the pandemic.

The disruptions have left some students worried about their safety, she said.

“Just the anxiousness of coming to school or being worried that you’re not going to get to take in all of the learning that you need, or being worried about getting into a fight at school—all those things they can lead to anxiety, which can then put you in such a dark place or make you have depression. It can just be a domino effect for other things,” Ridenour said.

Students are in school about eight hours a day, so a safe learning environment is paramount for their mental well-being, said Lawson Morris, 17, an Oskaloosa High student who also serves as a facilitator for the NASSP’s student-leadership network on mental health.

“Everybody is a creature of their environment, so the people we surround ourselves with have a major impact on our mental health,” he said. “So much of your life is spent at school, and if people around you are happy, then you are going to be happy. If people around are undisciplined and acting out, that’s going to [be] a reflection on you, and we really don’t want that, because we have a lot of good students in our school.”

After jotting down on sticky notes possible reasons for the rise in disruptive and disrespectful behavior, the students settled on short PD sessions for teachers that would be led by students. Those sessions would give teachers an inside look on why students may be acting the way they were and suggest ways that teachers might respond.

“We have been in the classrooms; we empathize with [teachers],” Morris said.

Elliot Nelson, 18, a member of Oskaloosa High’s student council, said students are looking to work in partnership with faculty.

“We don’t want it to be a lengthy lecture,” Nelson said. “We want it to be a collaborative discussion. We want it to inform them on recent events and how to handle [them].”

Getting buy-in from school leaders

The tough task for the students who participated in the summit comes with going back to school, getting the blessing from their various student governments, then seeking approval from administrators—if the rest of the student body decides it’s the right direction.

The Oskaloosa students are hoping to speak to their district’s school board early next month, and they’re optimistic, but realistic, that teachers will be on board for the student-led professional-development sessions.

“There might be a couple of skeptical teachers, but I think that teachers will be extremely receptive,” Morris said.

Carrie Bihn, a teacher who accompanied the students from Iowa, said she thinks most teachers will take to the students’ proposal.

“I think the buy-in from teachers will definitely be there,” said Bihn, who has been at the school for about a decade. “Honestly, I think the teachers are going to love learning from the kids, because they are the ones with the insights into how the teenage brain ticks.”

Bihn said it was “intriguing” listening and watching the students brainstorm.

“From top down, we hear student achievement, kids have got to pass classes and succeed,” she said. “And when kids were explaining what their issues were, it was way more personal. It was not what I was expecting. I really didn’t think the kids were going to say discipline and disrespect were the top two problems in our school. … Sometimes, I think only the adults see discipline in the district.”

Eleanor Hurley, the director of health services who also serves as an adviser for Cardinal Spellman High School’s National Honor Society, and Jason Deramo, the director of campus ministry, who accompanied the Cardinal Spellman students, said they were not surprised by the topics their students chose to home in on.

“It was eye-opening to see it from the students’ perspective for sure,” Hurley said. “But we have been seeing stress and anxiety across settings, with not only students but adults as well. This is something that’s a hot button right now, a hot topic, and I think the students addressed it with great maturity and expertise. I was very impressed with them.”

While the Cardinal Spellman High School students listed the quiet room for students to decompress as their second most viable solution and something to follow up on later, Daniel Hodes, the president and head of school, appeared amenable to the idea.

There are already areas on campus where students could seek assistance, such as the nurse’s office, the campus ministry office, a chapel, and a renovated counseling suite. But Hodes said he recognizes that not everyone is comfortable going into those spaces.

“Having a fifth space, which would be another opportunity for students to be able to find peace in the day—absolutely,” he said. Hodes said he was also open to his students’ priority solution—mental health days.

“Our faculty and staff have personal days available to them for those reasons, but our students are not afforded those same days,” he said. “I think it’s a worthwhile pitch and I am excited to hear the full pitch when the kids are done with it.”

That was good news for Sanchez and O’Neill.

“It’s really nice to hear that our ideas are being taken seriously, because as teenagers—at least for me—I feel like a lot of times, I’m sort of brushed off because I am so young,” O’Neill said. “But it’s nice to know that there are adults willing to listen and willing to take our ideas truly into consideration because we are living through a different time, especially after COVID.”

Students said they learned a lot seeing what their peers around the country had recorded as the major mental health challenges at their schools. Some of the issues, like substance abuse, did not resonate with everyone.

“I remember thinking that’s a hard topic for high school students to take on,” Nelson, the Iowa student, said.

But others topics were deeply familiar.

“A common theme that most people, in many schools, had was stress,” Sanchez said. “Stress is something that causes a lot of other problems in schools, and it’s kind of like the root of everything. If you don’t really reduce that, you can’t get to the other problems.”

Listening to students

The three-day mental health summit, which included panel discussions with students and experts, grew from the NASSP’s summer survey, which highlighted student mental health and the lack of resources in schools as major problem areas for school leaders, said Ann Postlewaite, the organization’s director of community. The organization hosts a once-a-month meeting with student leaders on mental health.

Postlewaite said more school leaders are leaning on students for their input on how to respond to these challenges because the students are “the constituents; they are the people in the building.”

The exercise to find a solution to a pressing problem was a learning experience for the adults, too.

Bihn, the Iowa teacher, was struck by the number of worksheets from the student groups that highlighted a version of isolation or lack of belonging as a major concern.

“They all had some kind of issue listed [where] kids felt alone,” she said. “I am a fixer, so my first [thought] was like how do I fix this? How do we fix things?”