I’m very excited that today, February 7th, Craig Watkins & Juliet Schor will be hosting a webinar: Connected Learning As Pathway to Equity & Opportunity, and I’m very sad that I’m going to miss it live. But I’ll send these provocations out over the etherwebs, and I’ll listen to the recording.

Watkins and Schor contributed to the new research report on Connected Learning--a framework for learning in a networked age that emphasizes the power of individual learners exploring their interests in the context of supportive learning institutions.

Courageously, the Connected Learning authors choose to situate their new report in the context of educational inequality in both formal and informal settings.

I use the term “courageously” because 1) it’s incredibly important to address the widening opportunity gap in informal learning between wealthy and working class youth, and 2) in my reading, it seems there is quite compelling evidence within the report that the enterprise of Connected Learning could contribute to these opportunity gaps, rather than ameliorate them. The road from the design principles of Connected Learning pedagogy to greater equity in society is a difficult one for me to follow (Rocks! Thorns! Glass!).

This work is really important and really hard.

The Connected Learning authors frame their pedagogy/philosophy in the context of the gross inequalities of educational experiences in the U.S. (and the Global North more broadly). They lay out well-known facts about the connections between family income and school experience, and they also provide less well-known data about rising inequality in informal learning. They cite recent work by Greg Duncan and Richard Murnane that shows widening gaps in family investment in educational enrichment. In the 1970s, wealthy families spent about four times more than low-income families on enrichment activities. In the 2000s, wealthy families spent seven times more than low-income families on enrichment activities. This is also happening the context of a dramatic narrowing of the curriculum within schools--the loss of arts, music, physical education, and social studies--as a result of high stakes testing and No Child Left Behind.

From the Connected Learning report:

The trend for privileged young people and parents to mine the learning opportunities of networked and digital media is one more indicator of how differential supports in out-of-school learning can broaden the gap between those who have educational advantages and those who do not. When the public educational system lacks a proactive and well-resourced agenda for enriched and interest-driven learning, young people dependent on public institutions for learning are doubly disadvantaged.

In other words, as profoundly inequitable as our national system of schooling is, the full picture of our national ecology of learning--including the domains at the heart of Connected Learning—is much worse (Rocks! Thorns! Glass!). The Connected Learning authors wisely recognize the risks they face in advocating connected learning outside of a framework of parity, “Without this focus on equity and collective outcomes, any educational approach or technical capacity risks becoming yet another way to reinforce the advantage that privileged individuals already have.” (This is a lovely way of summarizing what I’ve found in my own research.)

In today’s webinar, Watkins and Schor will be talking about a “pathways to equity and opportunity.” The pathways to opportunity are compellingly described in the Connected Learning report. Connected learning invites students to explore their interests, and connect those interests to academic learning and careers. The report describes a working class girl who pursues a passion for fan fiction, in a supportive community of fellow writers, which she parlays into admission at elite liberal arts colleges. It describes another young man who transforms a passion for web comics into a career running an online comics aggregator. New media creates new opportunity.

Sometimes when I read these stories, and their framing, they have a kind of Horatio Alger quality. To be sure, new digital outlets allow people with historically marginalized interests (fan-fiction, hip-hop, etc.) to find new pathways, outside of the traditional academic track, to personal fulfillment and professional success. But Horatio Alger protagonists are a symbol of opportunity, not of equity. New opportunities don’t promote equity if the opportunities disproportionately benefit the affluent.

Just a few days before the Connected Learning report was released, the New York Times ran an article about two high school aged girls, enrolled in a New York prep school, that started their own media project called the Do Not Enter Diaries, about teenagers’ bedrooms. It is a quintessential story of Connected Learning, where two girls explore their own interests and connect those interests to media production, publication, and career opportunity. At one point, the girls’ parents loan them $3,000 to license song rights for videos and hire a lawyer for various publishing tasks.

Of course, virtually any kid with a smartphone could in theory start such a project. But kids who don’t have to hold down a job for spending money or to support their family have less time than those who are free to fully pursue interests; and those who can borrow a few grand at the drop of a hat from their parents (c.f. Mitt Romney’s advice for young adults) are differently situated than those whose parents don’t have such means.

Again, I think the Connected Learning authors are very careful to raise these issues. It is in wrestling with them that the Connected Learning report leaves me with many unanswered questions. Part I of the report frames the challenge of learning as one squarely grounded in issues of equity. Part II of the report details the design principles of Connected Learning, and in my close reading, I find that issues of equity are largely absent from this section. In other words, it’s not clear how emphasizing a participatory, interest-driven, institutionally-connected learning network makes for more equitable learning opportunities, especially in the face of the facts about the wide gaps in educational enrichment spending (Rocks! Thorns! Glass!).

Put simply, if connected learning is about kids following their interests and building personal learning networks around themselves, then the affluent are considerably more capable of doing that then those of modest means.

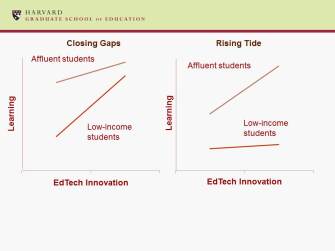

If it helps to think about this visually, let me present two models that I’ve shared before about the relationship between technology innovation (including theoretical innovation like Connected Learning) and learning.

The model on the right, “A Rising Tide,” hypothesizes that everyone benefits from new innovations like Connected Learning, but the affluent have more capacity to adopt these new ideas or tools and thus benefit more. The model on the left, “Closing Gaps,” hypothesizes that those of modest means disproportionately benefit from new innovations. To me, the overwhelming evidence provided within the body of the Connected Learning report suggests that the creation of new ideas, online spaces, and institutions related to Connected Learning are more likely to promote the scenario of a Rising Tide. The rhetoric of the report, however, suggests that the Connected Learning movement can achieve Closing Gaps, a greater parity in our grossly inequitable society.

I’m really looking forward to hearing Watkins and Schor describe how Connected Learning can support a more equitable society. The published report wonderfully explains why this is so important. But I’m still wondering how the Connected Learning movement can avoid the pitfalls that the authors, to their credit, so eloquently describe.

For regular updates, follow me on Twitter at @bjfr and for my papers, presentations and so forth, visit EdTechResearcher.