Anybody have any questions?” I ask. “How are things going on the playground?”

By including conflict managers as part of the district’s anti-violence plan, administrators want to cut down on tattling and trips to the principal.

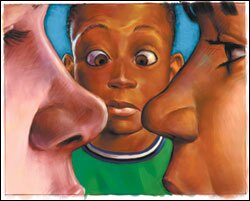

I’m meeting with our school’s conflict managers—40 Asian, Latino, black, and white 5th graders—to practice the conflict resolution skills I taught them a couple of months ago. The kids are spread across carpeted risers in the library, a mini amphitheater, looking down on me as though I’m an actress onstage. They’re quiet for now, but if I don’t keep things moving, I’ll lose them.

“Have there been many conflicts to resolve?” I continue.

A lanky girl with two braids raises her hand and then shouts, “A 1st grader threw a dirt ball at me, so I threw it back!”

They’ve had time to get over the excitement of carrying clipboards and wearing oversize navy blue T-shirts with a gold handshake logo. So today I’m hoping to work out any bugs in the schedule, see what they’ve forgotten, and role-play the conflict management steps again if they need it. Apparently they do.

I love this part of my job as school psychologist at an urban elementary school in Oakland, California. By including conflict managers as part of the district’s anti-violence plan, administrators want to cut down on tattling and trips to the principal. I want even more. I know that kids who solve their own problems are empowered. They learn something they don’t when adults resolve conflicts for them, or if they’re simply removed or punished again and again for playground squabbles. Our school’s 500 children are spilling out of the building into portable classrooms on the playground. We have bickering in lines, scuffles over kickballs, and occasional shoving matches to settle.

“What do we do if the little kids run away from us?” asks Michael, a boy in baggy pants and an equally loose-fitting basketball jersey. Michael’s mother is in jail for selling cocaine, and his father works two jobs. He gets into several conflicts a week—no fistfights yet, but he’s come close. Michael qualifies for the gifted and talented program, but his anger rips out of him like a bomb exploding, and I fear he’ll get sucked into the cycle of violence we’re trying to break. His teacher and I are giving Michael the privilege of being a conflict manager in hopes that he’ll learn something he can put to use in his life.

“If they run,” he asks me now, “do we chase ’em?”

Matt Collins

With hands on hips, my head cocked to the side, I moan. I must have gone over this 10 times during training; maybe it’s too late for some of these kids. But a boy in the back row answers correctly: “We ask a yard teacher for help.” So they did hear me.

Then a petite girl sitting cross-legged in the front row asks, “If the kids hit us, are we allowed to hit ’em back?”

This time I actually pull on my hair. “Hit them back?” I cry. “How many of you think you should hit them back?”

Half the hands go up. A few shout the affirmative. The rest look confused.

“You’re conflict managers! What do you think you do?”

No one answers.

Another girl raises her hand. “My auntie told me if someone hits me, I better hit back.”

I know the unwritten rules of their neighborhood. These kids don’t live in the roughest part of town, but they still need to stand up for themselves. Unfortunately, that’s often interpreted as fighting. This is not a new dilemma for me, so I tell the kids what I usually say.

“Not at school, you don’t.” I shake my head. “What are conflict managers supposed to demonstrate to the other students?”

I’m met with blank stares, a few tentative hands.

“To talk about it,” I say.

A couple of them shake their heads. “Then we’ll be a punk,” one student says.

Ignoring this comment, I announce, “Besides, if you hit someone at school, you’re no longer a conflict manager.” They know that two students already have been “fired” this year for getting into fistfights. “And,” I add, “you’ll get suspended.” I assume I’ve convinced them with this threat, but then the girl in front speaks again.

“If I get suspended, my mama says, ‘Oh well, you got suspended. At least you hit back.’ ”

The kids murmur in agreement and begin to talk among themselves.

I’m finally silent. I haven’t heard this before—I had no idea that suspension is seen as a minor price to pay for saving face. This is a no-win situation. “Why do you think we have wars?” I shout to the group, aware that I might be getting carried away. “Everybody has to keep hitting back!”

I have their attention now. “What’s wrong with this?” I add. “Somebody’s got to do something differently. We have to solve conflicts peacefully, with words. Please just follow the script on your clipboard. Help everybody get along.”

Why am I doing this— teaching kids skills they aren’t allowed to use outside of school and, worse, putting them in a bind if they do? It’s times like this I contemplate quitting.

Why am I doing this— teaching kids skills they aren’t allowed to use outside of school?

A week later, Michael finds me on the playground during recess. His conflict manager T-shirt hangs almost to his knees, and he’s pressing the clipboard to his chest. “Ms. Briccetti, I just resolved a conflict!” he exclaims, beaming. “These two boys were fighting over the tetherball, and I said, ‘Do you want some help solving this problem?’ And they said yes, and I said, ‘OK. What seems to be the problem?’ ” His voice warbles with excitement, and as he drops his clipboard to his side, I actually see him straighten, stand a little taller for a minute.

“That’s fantastic, Michael! And did they think up some solutions to their conflict?”

“Yeah, they’re going to take turns; they decided that on their own.” He’s glancing around the playground, either looking for more business or trying to see who’s noticing him; I can’t tell. “Now the little kids are following me around the yard, asking if they can help, too,” he says. His face is open, expectant.

“I’m proud of you,” I say, hugging his shoulder to my side. “Maybe you’ll be the one who starts to turn it all around.”

He gives me a funny grin, as if he’s humoring me, then struts off, clearly back on duty. At least, I think to myself, it’s a start.