Even the best-laid plans to reopen in-person instruction for the 2021-22 school year likely will need to adapt to the reality of a rapidly changing pandemic virus.

The Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes the fatal respiratory disease COVID-19, made up 1 in 10 new U.S. infections as of the two-week period ending July 5. Rochelle Walensky, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, predicted the strain, first identified in India, will overtake the Alpha variant from the United Kingdom to become the most common variant in the country within a few weeks.

Alpha and Delta are just two of four new varieties of the constantly mutating pandemic virus that are considered to be “of concern” by the CDC, meaning they cause faster infection, more-severe illness, and/or reduce the effectiveness of treatments or vaccines.

Here’s what educators need to know about Delta.

Why is the Delta strain so different?

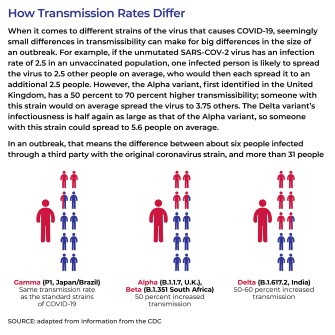

Delta is one of several new strains whose differences in the so-called “spike proteins"—which give the virus its signature pin cushion appearance—help the virus bind better to the surface of a cell. The variant is roughly 50 percent more infectious than the most-common current variant, Alpha, which was in turn about 50 percent more infectious than the original pandemic coronavirus. That could lead to an exponential growth in outbreaks in communities with limited vaccinations and lax masking.

Is the Delta variant worse for children?

Children now make up just over 1 in 10 new COVID-19 infections, with nearly 8,500 children infected in the week ending June 24, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics tracker. Since the pandemic began, children have made up more than 14 percent of all infections. One study in the British Medical Journal suggests the Delta variant is driving outbreaks in primary schools in the United Kingdom.

However, children are becoming a more visibly vulnerable group in the pandemic, both because more-infectious strains lead to more overall cases and because fewer children have been or are able to be vaccinated. While 58 percent of adults ages 18 and older have been fully immunized, only about 55 percent of those 12 and older have been fully vaccinated. And so far, there is no vaccine approved for children under 12, though Anthony Fauci, the director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the chief medical adviser to the president, has said he expects at least some vaccines to be available later this fall or in early 2022.

At this point, the Delta variant has not been found to cause more-severe illness in children than do other strains of the virus. About a third to half of children with COVID-19, including the Delta variant, have no symptoms, and “mortality in the 5- to 17-year-old bracket is extremely low with COVID. We’re talking on the order of two per 100,000,” said Danny Benjamin, a professor of pediatrics in the Duke School of Medicine and the chairman of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Pediatric Trials Network.

“Two per 100,000 doesn’t seem like much until you take into account that there 1.5 million, 5- to 17-year-olds in K-12 education” in North Carolina, for example, he said. “So now we’re starting to talk about nontrivial numbers.”

What role will vaccines play in controlling the new variants?

One reason certain variants like Delta are considered “of concern” is because they can limit the effectiveness of some treatments and vaccines. For example, while the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, one of the most widely used in the United States, is found to be 91 percent to 95 percent effective in protecting against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 two weeks after the second dose, Fauci noted, the vaccine is 79 percent effective in guarding against the Delta variant, and 88 percent effective in preventing those who do get infected from developing symptoms. Similarly, two doses of the Oxford-AstaZeneca vaccine were 60 percent effective in preventing infections and symptoms from the Delta strain. That could lengthen the time it takes for communities to develop herd immunity from vaccination, particularly in schools with children under 12, who do not yet have an approved vaccine.

How should school leaders account for variants when planning for school reopening in the fall?

The Delta variant’s higher transmissibility means that district leaders will need to keep a closer eye on infection rates in both the community and on campus, because outbreaks in either place can balloon much more rapidly.

While the CDC has relaxed overall masking recommendations for adults who are vaccinated, many states still require schools to use masks for adults and children if they hold in-person instruction.

“If the children have either widespread vaccination or widespread masking, then I would not make any substantive changes to plans for school. Children should be in-person, face-to-face,” Benjamin said.

By contrast, he said, “If I’m in a situation, whether I’m in North Carolina or Alaska, or Texas, where I’m in a school setting where the majority of the humans in the building are not vaccinated and not masked, then I can anticipate with the Delta variant a pretty substantial increase in transmission. And the types of things that I need to do are ... to focus on ventilation, to focus on testing, to have people outside as much as possible, and to look at some of the other mitigation strategies.”

Benjamin and Kanecia Obie Zimmerman, an associate professor of pediatrics in the Division of Critical Care Medicine at Duke and co-head of the National Institutes of Health pilot program that is studying safe school reopening, noted that in a yearlong study of 11 school districts in North Carolina that reopened in-person learning this year, those who used universal masking policies did not show an increase in infections.

“In fact, in the mask-on-mask environment or among vaccinated students, the risk of death from acquiring COVID in North Carolina this past year was less than the risk of riding to school in your parents’ automobile,” Benjamin said.

Zimmerman also noted that while some lab studies have found coronavirus could be transmitted on the surfaces of school supplies like pens, paper, or desks, in practice, constant surface cleaning has proven not as critical as vaccinations and masking when reopening schools.

“In the setting of masking, in the setting of hand-washing, the risk of transmission from those types of elements [like school supplies] is extremely, extremely low,” she said. Schools in the North Carolina study that rigorously enforced masking did not have higher infection rates even if they did not clean outdoor playground equipment as frequently, for example.

However, medically fragile children—those who have asthma, heart disease, diabetes, obesity, suppressed immune systems, or other severe or chronic medical conditions—are at higher risk from complications from COVID-19. Leaders of schools with high concentrations of these students may need a more stringent protocol for cleaning and distancing, even with lower community infection rates, and Benjamin noted that school leaders should consider how to adapt protections for groups of students with neurological or other problems who are not able to wear masks.