Corrected: The article should have said that Judy Johannes, the director of special education services for the Oconto Falls, Wis., schools, did not know exactly why special education referrals in her district have risen in recent years.

Janet Maltese’s voice rises above aural distractions, such as the humming air-conditioning unit, the clatter of students hustling through the hallway, and a lawnmower buzzing outside her classroom window. Even when she stands with her back to her 2nd grade class to write on the chalkboard, the youngsters can still hear her. But that’s not because she’s shouting.

Rather, the soft-spoken teacher is addressing her students through a wireless microphone clipped to her shirt. Amid all the usual classroom noises, her voice carries across the room thanks to one of the many sound-field-amplification systems installed here at the 4-year-old Sparks Elementary School.

“It really saves your voice,” said Ms. Maltese, a 28-year teaching veteran.

|

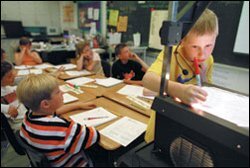

Tyler Geschwilm, 8, speaks through a microphone in a 3rd grade class at Sparks Elementary School. |

Such classroom sound systems are being praised by an increasing number of educators, who believe better sound will translate into better learning. “This is something the teachers can use for every kid, every day,” said Thomas N. Ellis, the principal of the 500-student school, which is in a rural, affluent community near Baltimore.

The units were installed in the school’s library, computer lab, and all 23 classrooms when the building was constructed four years ago, after a fire destroyed the former elementary school.

Speech and language experts say the new systems can help children both with and without hearing impairments.

Acoustics in a classroom are affected by three factors, according to Evelyn Williams, the director of audiology practice in schools for the Rockville, Md.-based American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Those are: background noise, such as the sounds of computers, heating and cooling units, and street traffic outside the windows; reverberation, or how much the signal, such as the teacher’s voice, bounces around the room; and the signal-to-noise ratio, or how loud is the teacher’s voice compared with the background noise.

Sound-field-amplification systems are designed to increase the volume and the clarity of the signal better than other measures. For example, putting carpet on the floor to cut down on reverberation “doesn’t do it,” said Ms. Williams.

|

Sound-amplification systems are helping educators speak more loudly and clearly. |

The amplifier units at Sparks Elementary, which were manufactured by the Burnsville, Minn.-based company Telex, look like small, inverted pyramids hanging from the ceilings of the classrooms.

The teachers have a choice between using small lapel microphones that clip to their clothes or microphones on headsets they can wear over their heads or let dangle around their necks. The microphones attach with thin black wires to small battery packs that teachers clip onto their belts or to lanyards they wear around their necks.

Other companies—such as Audio Enhancement, Lightspeed Technologies, and Phonic Ear—make similar amplification systems and units that use portable speakers or speakers that sit on bookcases or tripods around the classroom. The systems can cost anywhere from $750 to $1,500 per classroom, depending on the kind used. They can be purchased for less than most classroom computers, said Mr. Ellis.

Though amplification systems were originally designed for students who had mild to moderate hearing loss, Mr. Ellis said he did not buy the speakers for that purpose.

After researching how the systems work and talking to teachers and speech and language pathologists who had used them, he decided they would benefit all of his students.

Mr. Ellis said the investment has paid off, as he has seen an increase in his students’ achievement, which he attributes partly to the fact that students can hear their teachers and classmates better.

“I think it has had an impact,” he said.

Mumbled Responses

Last week in Ms. Maltese’s class, the youngsters were gathered in a corner listening to their teacher read a book about skeletal systems. Ms. Maltese stopped after reading the word “exoskeleton” and asked the class to define the word.

She then unclipped the lapel microphone from her shirt and held it up to the mouth of a blonde boy, who mumbled: “A skeleton that covers the insect’s body?”

Yet even though the student mumbled his response, everyone in the room heard his answer.

That’s important, said Ms. Maltese, because she does not always have to repeat what students say. Constantly repeating what students have said “isn’t good because they learn to listen only to you,” and not to each other, she said.

Some teachers and speech pathologists believe that the systems are especially helpful to students who have attention problems, because the better sound has the effect of virtually putting every student in the front row of the class facing the speaker. “You don’t have to make sure that [a student with an attention problem] is right by your side,” said Ms. Maltese.

That was certainly evident to Sheila Guttman, who teaches 3rd grade here. She had to go 10 weeks this year without her microphone because the wire that connected her headset to the battery pack broke, which is a common problem, according to Mr. Ellis.

When she was without the microphone, she said she lost her voice a couple of times and suffered several sore throats. At first, “none of us really wanted to wear these things,” said Ms. Guttman. “But once you get used to it, it’s hard to go back to raising your voice.”

And her students could tell the difference, too. Without the amplification system, “you couldn’t hear her questions,” said Tim Butler, a student in Ms. Guttman’s 3rd grade class.

Student chatter also rose significantly when the system wasn’t being used. When her teacher uses the amplification system, “everybody won’t talk as much,” asserted Stephanie Tarlton, another of Ms. Guttman’s pupils.

To illustrate the point, Ms. Guttman turned her microphone off and held a brief conversation with Mr. Ellis. As she turned back to the students, who were all talking, she asked them to quiet down without using the microphone.

Some of the 28 students quieted down, but most kept talking.

When Ms. Guttman turned on the microphone and asked the class to settle down again, the room fell silent.

‘Concentrate and Hear’

Yet despite claims that the sound systems can help raise student achievement, increase students’ attention, decrease teachers’ voice strain, and aid in classroom participation, they are not a panacea, educators said.

In an effort to lower the number of students being referred for special education services, the Oconto Falls, Wis., school district installed sound-amplification systems in every kindergarten through 5th grade classroom. By the end of the 1998-99 school year, eight months after the units were installed, the 2,000-student district saw its special education referrals cut in half from their levels of the previous nine years.

But the number of referrals has slowly crept back to the level where it was before the systems were installed, said Judy Johannes, the director of special education services for the district.

Part of the reason could be that teachers in the district are not using their microphones as much as they were in the first two years, she said. Unlike the educators at Sparks, the teachers in Oconto Falls “don’t like having them on, or they don’t like wearing them,” said Ms. Johannes.

To drum up more enthusiasm for the amplification systems, principals in the district have been encouraging teachers to use them more often, she said.

And Ms. Williams of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association believes more teachers will use them once they see the impact they can have on student learning.

Without high-quality classroom acoustics, she said, “teachers fatigue because they have to strain their voices, and the children fatigue because they have to strain to concentrate and hear.”

Coverage of technology is supported in part by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.