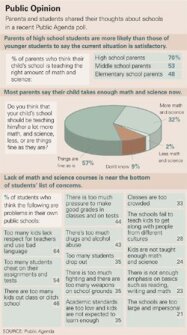

Parents and students don’t feel the same sense of urgency about mathematics and science education that President Bush and many business and education leaders do, a survey suggests.

While the president is calling for beefing up instruction in those subjects as part of his American Competitiveness Initiative, parents may need more convincing that such a strategy is needed.

“Are Parents and Students Ready for More Math and Science?” is posted by Public Agenda.

According to the Public Agenda poll, scheduled for released this week, 57 percent of the parents surveyed think their children are already learning enough math and science.

And, when asked to list their concerns for students, the need for more math and science classes fell near the bottom, with issues such as dropout rates, fighting, and a lack of respect for teachers ranking much higher.

The report’s authors say the results suggest that government, business, and education leaders—who have stepped up their advocacy of improved math and science performance as vital to the nation’s economic well-being—are not getting their message across.

Corporate chief executives and education experts “believe today’s schools aren’t as challenging as they need to be and that students just aren’t learning enough,” says the report, “Are Parents and Students Ready for More Math and Science?”

“But parents start from a vastly different mind-set,” it adds. “Most are convinced their own children will be well prepared for college or work when the time comes.”

Attitude Shifts

Attitudes about math and science have shifted since the mid-1990s.

Parents and students shared their thoughts about schools in a recent Public Agenda poll.

*Click image to enlarge

SOURCE: Public Agenda

In 1994, more than half the parents surveyed in a similar Public Agenda poll thought that insufficient math and science education for their children was a serious problem in their local public schools. But in the new survey, only 32 percent considered the issue to be a serious problem.

Shirley Malcolm, the director of education and human resources at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in Washington, said one reason parents might feel less urgency today is that states have placed a lot of emphasis on raising academic standards.

But more work needs to be done, she said, to create curricula “that will produce the kinds of students that we say we need.”

The new survey also found that high school students feel about the same toward math and science regardless of gender. Fifty-eight percent of girls and 55 percent of boys agreed that increasing the number of required math and science courses would improve high school education in the United States.

Differences show up, however, between the views of white high school students and their peers from minority racial and ethnic groups. While 53 percent of the students from minority groups agreed with the statement that having strong math and science skills is “absolutely essential” before graduating and going out into the postsecondary world, only 48 percent of white students said they felt the same way.

African-American students were more likely than whites or Hispanics to say that students’ not being taught enough math and science is a “serious problem.”

An Ongoing Project

The survey is the first installment in Public Agenda’s Reality Check 2006, a series of public-opinion tracking surveys on education issues by the nonprofit opinion-research organization, which is based in New York City.

It’s also part of Education Insights, a multiyear initiative at the organization to involve more parents and community members in issues affecting education.

For this survey, Public Agenda held two focus groups with parents. Between Oct. 30 and Dec. 29 last year, the group also conducted two telephone surveys with national random samples—one of 1,329 parents with children currently in the public schools and another of 1,342 students in grades 6-12. The margin of error is 3.8 percentage points for the parent sample, and 3.4 percentage points for the student sample.

Michael Cohen, the president of Achieve Inc., a Washington-based organization formed by governors and business leaders that focuses on raising academic standards and student achievement, said that too often, students don’t realize they’re unprepared for postsecondary education or even employment until they have been out of high school for a few years.

Perhaps parents need to think about the issue, he said, in real-world terms: weighing the costs of remedial high-school-level courses in college or having their grown children moving back home because they couldn’t get jobs.