(This is the third post in a five-part series. You can see Part One here and Part Two here.)

The new “question-of-the-week” is:

How can teachers use questions most effectively in the classroom?

Part One‘s commentators were Jeri Asaro, Dan Rothstein, Diana Laufenberg, Rebecca Mieliwocki, Jenny Edwards, Scott Reed, Cara Jackson, and Ben Johnson. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Jeri and Dan on my BAM! Radio Show. You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Part Two‘s contributors were Sean Kelly, Sidney D’Mello, Shelly Lynn Counsell, Dr. Jennifer Davis Bowman, Rachael Williams, and Jeffrey D. Wilhelm.

Today, Tan Huynh, Laura Robb, Judy Reinhartz, Ph.D, and Erik M. Francis share their suggestions.

Response From Tan Huynh

Tan Huynh is a Teach For America alumnus and the head of the English Language Acquisition Department at Vientiane International School, an International Baccalaureate World School. He shares his classroom-tested, research-supported strategies on his blog:

Questions are the currency of learning. A thought-provoking question can produce buy-in from students for a sustained period of time. Questions also reveal gaps in understanding and skill development. If questions are the currency of learning, then student-generated questions are the geese that lay golden eggs. Sadly, most questions do come from teachers and are but entry-level checks for understanding. To return question-making back to students, simply put, we must create a culture of asking questions.

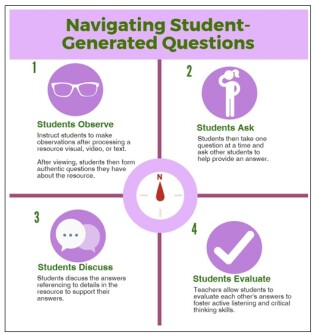

4 Steps to Navigating Student-Generated Questions

- Students Observe

Questions spring from attentive observations. Traditionally, we trample over the opportunity for students to be observant and curious because they know there’s going to be a monsoon of comprehension questions flooding their worksheets.

Why be observant when the teacher will tell you what to observe through the questions he asks?

One strategy to help students observe is to have them produce questions before reading a text, watching a video, engaging in a simulation, or processing an image. For example, I gave give my students this text from Newsela entitled, “Women around the world on strike, or at least on pause, in solidarity”. I simply asked, “What questions do you have from reading the title and looking at the image?” They asked the following:

- Really? All around the world?

- How did they organize this?

- What’s a strike?

- What’s the difference between pausing and striking?

- What’s solidarity?

- When did this occur?

- What are they striking against?

- How many women in total?

Many of these questions could be answered by the texts, and many would require inferencing skills. However, they all showed that the students were engaged and prepared to read the text to find their answers. But these were not the only questions they generated—I had them annotate the text with new questions as they read. These are not tes—your knowledge questions, but rather authentic questions that students want answered by the class they are taking.

Teachers should hold off on providing guiding questions because answering teacher questions is only a task to complete, but students seeking their own answers transforms reading into an investigation. Moreover, from my experience, most of the questions they ask are the ones we wanted to test them on anyways.

- Students Ask Questions to Each Other

After they finished reading the text, I have them form small table groups of four students and ask their questions to each other. Small group talk encourages shy students to talk, and everyone has a chance to speak.

- Students Discuss

As students take turns asking questions, they then answer them for each other. What one student misses, another student often gets. The small group talk prevents me from being the sage on the stage. It shifts the responsibility back to students. It also develops a culture of collaboration and mutual dependence. Students know that their classmates are there to support them in constructing meaning from the text.

- Students Evaluate

In traditional, teacher-centered classrooms, students answer a teacher-generated question and wait for the teacher’s evaluation. In a culture that honors student-created questions, in contrast, we allow students to validate each other’s answers because we want them to do the thinking and evaluating. When teachers judge their responses, we are robbing students of this rich thinking activity.

Many teachers who are not used to this culture of questioning will protest with, “How do I know the group will produce the right answer?” To which I say, “Let the text support their answers.” This means students don’t just answer how they want; their claims have to be supported by the texts.

The teacher’s role here is to float around and make notes of the things students are saying and asking. At the end of the discussion, you can take these notes and highlight thoughtful ideas and quality of the collaboration. However, as you float, intervene when students are attacking each other instead of respectfully disagreeing with ideas.

A Compass, not a Map

When teachers ask questions, we provide students with a map that leads them to predetermined destination. However, when we gift students with the opportunity to form questions and have other students collaboratively answer, we provide students with a compass that leads them to their desired destination. We cannot provide them with a map of their future, but we can equip them with tools and processes to navigate their journeys—wherever they lead.

Response From Laura Robb

Laura Robb’s most recent book is Read, Talk, Write: 35 Lessons That Teach Students to Analyze Fiction and Nonfiction:

When Students’ Questions Define a Classroom

The practice of asking questions to drive students’ learning is alive and well in schools today. But here’s the rub! Too often questioning is actually recitation where the teacher prompts students for the “one right answer” to questions she has developed. Moreover, at school, who should be posing the questions? To foster independent readers and thinkers, students need to be in the driver’s seat when it comes to asking and answering questions. If teachers always control questioning, then student learning is greatly diminished because students aren’t discussing ideas that have relevance for them.

On the other hand, when quality, student-generated questions define a class, meaningful learning takes place—learning that defines reading, research, collaborative projects, literary discussions, and units of study. As students wonder and question and use their questions to learn, they develop the ability to raise questions while reading. This keeps them focused on a text, but also motivates them to read on to find answers to their queries.

When Do Students Ask Questions?

Opportunities abound throughout the day for students to pose questions. Here are a few:

Mini-lessons: Invite students to jot down questions they have while you present a mini-lesson and ask these when you’ve finished. Such questions clarify students’ understanding and help them absorb new ideas. However, students’ questions can offer you insights into what they do and don’t understand. With this information, you can design interventions based on observed needs.

Daily teacher read alouds: Frequently, students pose questions about a conflict, theme, or how events connect. Reserving a few minutes for students to ask their questions shows them how much you value their thinking and provides you with insights into ways students react to the text.

Setting goals: Help students understand that raising two questions such as, Is there a strategy I should work on next? What do I have to do to reach this goal?” can improve their learning. Such questions develop independence because they place students in charge of decision-making.

Self-evaluation: Questions can also drive students’ evaluation of their work over time, such as reviewing several journal entries in their notebooks, the entire process for a piece of writing, several quiz and test grades, or their participation in collaborative projects. Here’s a sampling of questions that students might ask: Did I improve? How do I know I made progress? Is there something I did that stands out? Did I struggle? How? What did I do to cope with my struggles?

A result of self-evaluative questions is the development of metacognition, the ability of students to reflect on their written work, collaborations, and learning to improve critical thinking and problem solving.

Close reading: Isabel Beck and Margaret G. McKeown’s strategy, questioning the author, provides students with questions for fiction and nonfiction texts. The questions help students link words, phrases, and ideas to construct meaning from a passage they find challenging. While close reading, student might ask: Why did the author use that word or phrase? How does the word or phrase connect to the information in the sentence? To information that came before the sentence? How does the paragraph or section connect to the title? The theme or main idea? The previous paragraph or section? These questions can develop independence in unpacking meaning from challenging passages in texts.

Inquiry-based learning: Before and during a unit of study, students generate questions that drive their reading, investigations, experiments, and discussions. Researchers like Jeffrey Wilhelm and Michael Smith, show that when student-generated questions steer the direction studies take, they are more engaged and motivated to learn. Inquiry fosters collaborating, recalling and understanding information, analyzing texts, and meeting deadlines. Students enjoy the process far more than when teachers direct and control students’ learning.

Reading texts: Teach students how to pose open-ended, interpretive questions and invite them to work as a team when reading an assigned or self-selected text. Open-ended questions have two or more answers. Verbs such as, why, how, evaluate, explain, compare/contrast can signal interpretive questions. Returning to a text to write open-ended questions deepens students’ knowledge of plot and information, but it also raises the level of discussions to analytical and critical thinking. In addition, discussing their own questions motivates and engages students in the reading and in exchanging ideas.

The Teacher’s Role

Providing a model for students, one that shows them how to raise questions during diverse learning experiences is a primary job of teachers. Becoming a skilled questioner won’t happen quickly for most students. However, turning the questioning process over to students gives them opportunities to practice and to make their studies more meaningful. Equally important, when students are in charge of questioning, they develop independence in learning.

Meaningful reflection by teachers and students—reflection that considers improving questioning techniques and gathering feedback—can create a learning environment that values students’ questions as a path to progress in all subjects.

Response From Judy Reinhartz

Dr. Judy Reinhartz’ career spans over five decades in K-16 education as an elementary and secondary teacher, educator of preservice and inservice K-12 teachers, administrator, and director of centers, academies, and institutes. She is an author of nine books and numerous articles on a variety of academic and pedagogical interdisciplinary topics that bridge literacy and science learning, a staff developer working with university, elementary, and high school teachers and administrators, presenter at local, state, regional, national, and international conferences, investigator, and consultant who strives to connect research findings to best classroom practices:

How Do We Know Students Know? ...

There are many ways to answer this question, but formulating questions on the spot during lessons is not the answer. The answer to “How do we know?” lies in planning the types of questions to elicit different levels of thinking and planning response strategies that include the time teachers wait to follow up with students. Both unlock the power of questioning.

On average, teachers ask between 300-400 questions every day, and as many as 120 per hour in rapid-fire fashion. Such questions are often asked without advanced planning, resulting in “skinny” questions that serve to check students’ factual knowledge by asking who, what, when, and how questions. Skinny questions play a role in lessons, but we should not sacrifice the opportunities for students to apply, analyze, evaluate, and create something new from the content they are learning. As Josef Albers notes, asking the right questions at the right time can be as important as knowing the right answers. As teachers, we should strive to ask higher-order questions to challenge students to make connections and to think more deeply about what they are learning.

The ability to ask quality questions does not just happen; it is an acquired skill and takes time and effort. Our role should be to harness the power of questioning by providing students with opportunities to practice and retrieve information in ways that give them permission to pose and answer their own questions and make own mistakes as they answer them.

Here are a few tips for honing teacher questioning skills. Teachers should:

Set clear learning goals with clear criteria to provide students with evidence of what they learned using templates such as, “I can ...” “Here is my evidence ...,” and “Yes” or “Not Yet.”

Provide specific input about how students can reach their next learning goals by writing both content and language objectives and offering specific nonjudgmental feedback.

- Hold many dress rehearsals to prepare students for their final performances (unit/semester tests, yearly exams, mandated state tests). These rehearsals include asking and answering an abundant number of questions that in turn paint a clearer picture of where the learning gaps are and setting the stage for what comes next instructionally.

Planning questions is step one; step two is formulating response strategies to use after students answer. It is important to be patient and use wait time after asking questions. This strategy gives students time to formulate an answer individually before sharing with the whole class. Here are a few other response strategies to consider. If students’ answers include:

New ideas, ask “Can you tell me more?” and “Where can you go to get more information?” to push them to provide the reasoning underlying their thinking.

Partial information, reinforce their contributions with “You are on the right track” and encourage them to ask a neighbor to add more.

Inappropriate information, determine if it is content or language based ask “What do you know about _____?” to gather more information regarding the student’s level of understanding.

- Silence, ask if they can gesture or draw their answer to let them know that you will be coming back to them when they are ready; encourage them to ask a neighbor for some ideas.

If students respond in a language other than English, encourage them by saying, “Thank you for answering.” Ask the students’ partners, “How do you say that English?” and then repeat the question and model the response in English. If students respond with questions say “What good questions, thank you for asking them.” And, “Does anyone have an answer?” or “Would you like to ask someone in the class for an answer?”

It takes practice to ask better, strategic questions since they are an integral part of a teacher’s repertoire. Teachers who take the time to plan quality questions and develop response strategies gain greater insight into what their students know and the degree to which connections that have been made. Through planning, teachers get closer to answering the question: “How do we know students know?”

For more information about the power of questions, check out my book, “Growing Language Through Science: Strategies That Work” (2015) by Corwin Press or email me at jreinhartz@utep.edu.

Response From Erik M. Francis

Erik M. Francis, M.Ed., M.S., is the author of Now THAT’S a Good Question! How to Promote Cognitive Rigor Through Classroom Questioning, published by ASCD. He is also the owner and lead professional education specialist for Maverik Education LLC, providing professional development on teaching and learning that address the cognitive rigor of college and career ready standards. He also provides consultation on the development, implementation, and compliance of academic programs funded under policies and provisions the Every Students Succeeds Act (n.e. the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965):

Traditionally, we educators use questions to assess student learning. We ask the question, the student responds, and we tell them if they’re correct or incorrect. We also expect students to respond immediately. With good questions, students don’t need to answer the question right now and there in that moment. When you ask a good question, you’re actually setting the instructional focus for the lesson or unit. That’s one of the qualities of a good question. They are so deep and powerful that they can drive the instruction and determine how deeply or extensively a students knows, understands, and can transfer and use what they have learned.

You can also rephrase the objectives of standards into good questions that will not only serve as assessments but also set the instructional focus for a student learning experience. Instead of posting the standard or objective as a TLWD or TSL or SWBAT statement, write or pose a good question that not only introduces the topic but also gets the students thinking about what they are about to learn. For example, you can walk into a classroom and start a lesson or unit by asking, “How can a rational number be understood as a point on the number line?” That’s actually the objective of the standard—Understand a rational number as a point on the number line. However, by rephrasing it as a good question, you’re not just directing students to do this. You’re informing them, “This is what you’re going to learn. This is what you’re going to examine and investigate. This is the info you need to acquire and gather. These are the concepts and ideas you need to apply or consider.” Then you let them go acquire and gather that information and report and explain what they have learned.

The best way to become better at instructing through inquiry is to just keep asking questions. Every time you want to tell the students something, phrase it as a question. Instead of telling them, “Edgar Allan Poe created the detective mystery genre with his tales of ratiocination,” ask, “How did Edgar Allan Poe create the detective mystery genre?” You’ll mostly likely hear the crickets, but you can break the silence not by answering the question for the students but by asking, “What if I told you that Edgar Allan Poe wrote the world’s first detective story, that he called them tales of rationcination, and that Sherlock Holmes is actually based on this character Poe created decades earlier?” Now you’ve peaked their curiosity and interest, and then you can challenge students to use their devices—their phones or their 1:1s—to confirm whether this is true and learn more. They’re teaching themselves, but most important skill they will need in life—how to acquire and gather information they need and how to consider whether the information or sources is credible or true.

However, don’t expect students to provide an immediate answer. Students don’t answer good questions. They address and respond to them. Good questions challenge students to think deeply and express and share the depth and extent of their learning. They expect students to take the time and make the effort to consider and craft their responses.

Also, don’t just accept a simple answer or a statement repeated or rewritten from the book. When a student answers a question with a short or simple response, always ask, “What do you mean?” Have the student elaborate or explain or even justify your response. You can also do that as a check for understanding. If you ask a student, “What is 5 x 4?” and they blurt out, “9!” instead of “20!”, you can ask, “What do you mean?” That will not only have them explain but also correct themselves and realize their mistakes.

If you want to become more effective at instructing through inquiry, simply shift your approach and delivery. Don’t just instruct—inquire. Don’t just show and tell what they need to know and do—ask them to show and tell what they have learned. Also, don’t worry if you don’t receive an immediate response or the room falls silent. That’s part of the inquiry-based learning experience—the quiet wait time students use to think, to reflect, and consider how they want to respond.

Thanks to Tan, Laura, Judy, and Erik for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Anyone whose question is selected for this weekly column can choose one free book from a number of education publishers.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Just a reminde—you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And, if you missed any of the highlights from the first six years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. They don’t include ones from this current year, but you can find them by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Best Ways To Begin The School Year

Best Ways To End The School Year

Student Motivation & Social Emotional Learning

Teaching English Language Learners

Entering The Teaching Profession

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributers to this column.

Look for Part Four in a few days..