Editor’s note, July 8, 2020; Updated March 18, 2021: The author of this piece, which was originally published on the Conversation, contacted Education Week to acknowledge to us that she failed to attribute the phrase “fragile math identity” to the researcher who coined the term—Ebony McGee, an associate professor of diversity and STEM education at Vanderbilt University. The author also misused the term, which describes how negative racial stereotyping motivates Black students to disprove negative profiling in mathematics education settings. The essay has been updated, and the term has been dropped. Education Week has elected to publish a different version of this essay from what currently appears on the Conversation, as we believe it is more accurate to the original essay we published.

I teach people how to teach math, and I’ve been working in this field for 30 years. Across those decades, I’ve met many people who suffer from varying degrees of math anxiety. In its worst manifestations, math anxiety becomes what my colleagues and I call math trauma—a form of debilitating mental shutdown when it comes to doing mathematics.

When people share their stories with me, there are common themes. These include someone telling them they were “not good at math,” panicking over timed math tests, or getting stuck on some math topic and struggling to move past it. The topics can be as broad as fractions or an entire class, such as algebra or geometry.

The notion of who is—and isn’t—a math person drives the research I do with my colleagues Shannon Sweeny and Chris Willingham on people earning their teaching degrees.

One of the biggest challenges U.S. teacher-educators face is helping the large number of elementary teachers who are dealing with math trauma. Imagine being tasked with teaching children mathematics when it is one of your greatest personal fears.

Math trauma manifests as anxiety or dread, a debilitating fear of being wrong. This fear limits access to life paths for many people, including school and career choices.

While math trauma has multiple sources, there are some that teachers have power to influence directly, including outdated ideas of what it means to be good at math.

For instance, speed and accuracy were important in decades past when humans were the actual computers. But research has confirmed what many people share with me anecdotally: Tying speed with computation debilitates learners. People who struggle to complete a timed test of math facts often experience fear, which shuts down their working memory. This makes it all but impossible to think, which reinforces the idea that a person just can’t do math—that they are not a math person.

What’s more, students who succeed at tests of timed math facts may believe that being good at math means simply being fast and accurate at calculating. This belief can lead to a math identity that is tenuous. Students fear revealing they don’t know something or aren’t that fast, so may shy away from more challenging work. No one wins.

The myth that fast recall of basic math facts should be drilled into children has deep and pernicious roots. It comes from the best of intentions—who wouldn’t want kids to be good at calculating? But research shows that automaticity (the ability to easily recall facts, like 3 x 5 = 15) is best developed from first making sense of arithmetic operations. In other words, the first step in building a mathematical memory is understanding how that math works.

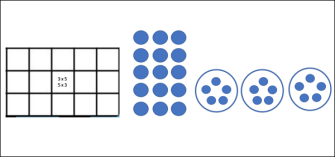

As an example, the area, array, and equal groups models in the image below represent multiplication and division fact families. These models can help students focus on making sense of the related facts 3 x 5 = 15, 5 x 3 = 15, 15 ÷ 3 = 5, and 15 ÷ 5 = 3. They can be used to assess fact fluency and automaticity.

Credit: Holly Pope

Skipping the sensemaking step makes for fragile understanding and cognitively expensive memorization. When someone only memorizes, every new fact is like an island unto itself, and is more readily forgotten. In contrast, understanding patterns in math facts compresses the cognitive load required to recall related facts. Sensemaking promotes deep, robust, and flexible understanding, allowing people to apply what they know to new problems.

So what can teachers do to support fact fluency?

First, find the wonder and joy. Games and puzzles that get people playing with numbers, such as KenKen or facts-based card games, create an intellectual need to use math facts that helps kids develop fact fluency. Asking kids to explain their thinking—using words, pictures or objects—validates the importance of their ideas.

Reframe mistakes as explorations. Not having a correct answer doesn’t mean all thinking is incorrect. Asking kids to explain their thinking also helps in understanding what they know now, and what they might learn next. Questions about how a kid got an answer can get them thinking about what does not quite work and is worthy of revision. When you ask these questions, it’s good to have a poker face; if you broadcast that an answer is wrong or right, it can reinforce the belief that only right answers count.

Second, do no harm. It’s important that teachers avoid giving kids messages that they are not math people. This can have a negative impact on kids’ beliefs about their own ability to learn. Also, beware claims that kids must suffer to learn mathematics.

Teachers can help parents by clarifying that while mathematics may not have changed, teaching and learning methods have. For many adults, today’s math classes are very different from those we experienced as children. U.S. schools have moved away from speed and accuracy—sometimes called “drill and kill”—and toward discussing and making sense of mathematics.

Many parents express concern that, whereas they had to learn “only one way” of solving problems, their children now must learn several. This is a valid fear for parents who struggled to use mathematics that made little sense to them—they envision the problem compounded for their children. They need to know that multiple methods are not intended for rote memorization, but rather to express and honor the different ways children come to understand mathematics.

Mathematics teacher educators are in agreement that changes supporting teaching and learning for sensemaking are helpful. We now seek more meaning in what children are learning, knowing that deeper understanding comes from connecting multiple ways to solve problems. And we learn much better from a sense of joy and wonder than from fear or dread.

This doesn’t mean that students won’t ever struggle in a math classroom. But it’s important to differentiate productive struggle, which helps kids develop persistent mindsets in learning mathematics, from debilitating struggle. We can help our students by normalizing the confusion we experience when we are first learning something new. We can celebrate the clarification that comes with making sense of mathematical work. And we can remind students that anything we struggle to learn becomes a mighty achievement.

If you recognize that you are a survivor of math trauma, take heart. You are not alone, and there are ways to heal. It starts with understanding that mathematics is broad and beautiful—most of us are much more mathematical than we think. Find ways to play with math and look to learn from your students—they are often our best teachers. Doing math—with wonder, productive struggle, and the joy of discovery—is the best way to get better at it.

A previous version of this piece was published on The Conversation. Read the original article.