Matthew R. Kay agreed to answer a few questions about his new book, Not Light, But Fire: How to Lead Meaningful Race Conversations in the Classroom.

Matthew Kay teaches students at Science Leadership Academy in Philadelphia.

LF: I certainly can’t say that I’ve read every book discussing race and racism in schools. However, I would be very surprised if there was another one out there that did a better job than yours of providing practical, nuanced, and helpful perspectives to teachers who are grappling with how to approach it in the classroom.

In the Introduction, you highlight Frederick Douglass’ perspective on dealing with race and racism:

[Douglass] called for us to infuse our conversations with fire--to seek out and value historical context, to be driven by authentic inquiry, and above all, to be honest--both with ourselves and with those with whom we share a racial dialogue.

Before we get into specific classroom instructional actions teachers can take with students, I’d like to deal with a different question:

What suggestions would you have for teachers who want to have those kinds of conversations with colleagues who claim they “don’t see race” in the classroom or, who see it and feel no need or desire to bring it into their lessons?

Matthew Kay:

My advice to them would be simple: work on your own practice. Do not exhaust your limited energy engaging colleagues who deny the premise that race is visible. Build instead among like minds that want to get better at this stuff. Then, when your successes become apparent - and your students are on fire - more colleagues might be willing to engage the idea.

I would remind teachers that there are levels to this work. At the baseline level, we learn the importance of “seeing race,” of accepting the existence of privilege, of recognizing the inherent value of different cultures. We learn that we have much to learn, and always will. Teachers who have not reached this level are not ready to make good use of my book. They should instead read Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility, Carol Anderson’s White Rage, or Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning, works that break down both privilege and the ubiquitous role that race has always played in our country’s social order. A person, a teacher especially, who can live in this world and not yet “see race,” has been an insufficient scholar - who has a whole lot of work to do before even thinking about broaching the topic with students.

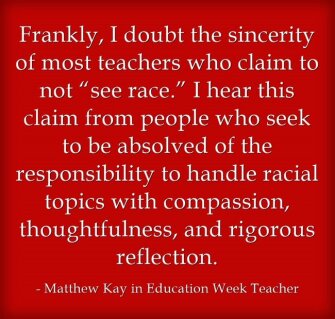

Frankly, I doubt the sincerity of most teachers who claim to not “see race.” I hear this claim from people who seek to be absolved of the responsibility to handle racial topics with compassion, thoughtfulness, and rigorous reflection. People who do not “see race” conveniently find themselves never needing to get better at anything. The claim is dishonest. They “see” it just fine.

To teachers who “see” race and feel no need or desire to bring it into their lessons, I earnestly ask, “Why don’t you?” There are a few viable reasons why one would not wish to insert race into any particular classroom conversation. Sometimes it is not relevant. But we must reflect on how often we have unintentionally forced race talk to the sidelines. How have we, deliberately or not, kept black and brown authors telling black and brown stories from being considered curriculum-worthy? How have we chosen which histories are worth teaching? Which lenses should be used to study them? It’s helpful to think about the habits and systems that keep race out of one’s lessons, and work to remove these barriers so that otherwise relevant - and often quite engaging - race angles are no longer ignored.

Finally, some educators “see race,” but do not know how to lead meaningful race conversations in the classroom. Not Light, But Fire is for them. In it, I offer practical advice, based on both my hard-won successes and my multiple missteps. The result, I believe, is a comprehensive and flexible method for getting the most value from these conversations. Not Light, But Fire also recognizes that the work is hard, and the wins are complicated, so my work aims to remind teachers of good will that they can do it, and that their mission is worthwhile.

LF: You talk about the importance of teachers creating “conversational safe space” in the classroom for discussions about race and racism, and to establish it with three guidelines:

Listen patiently, listen actively, and police your voice.

I love one example you share on how not to do it and on how to do it:

(A)

Mike (interrupting Joe, a classmate): Yo! That same thing happened to me yesterday when ...

Mr. Kay (frustrated): One voice! You’ve got to stop interrupting!

Mike (equally frustrated, whispering to a classmate): Told you Mr. Kay doesn’t like me.

(B)

Mike (interrupting Joe, a classmate): Yo! That same thing happened to me yesterday when ...

Mr. Kay (smiling, holding up a placating hand): Patience, man! Listen to Joe--he’s making a good point! Tell your story in a bit.

Mike: Oh, my bad, Joe.

It’s connected to recent research on the effectiveness of emphasizing to students how their actions impact others.

What do you think is the hardest one of those three parts for teachers, and can you elaborate on some of your suggestions on how they can get through it?

Matthew Kay:

I do not think that any of the three skills is harder to develop than the others. However, if I had to choose, I would be tempted to pick listen patiently, as it has to come first. Whenever we are discussing something that we are passionate about or disagree with someone else about, it’s easy to focus most of our energy on preparing our own contributions. In doing this, we make a minimal investment in listening to others. At our best, we simply wait our turn, formulating our responses while our partners are speaking. At our worst, we interrupt. Teaching students to listen patiently to each other runs counter to most of what they see from adults engaging in race talk. On news networks and on social media, students rarely see adults listening patiently to each other. In fact, many pundits talk race with habits that we would never want our students to adopt. They interrupt constantly. They speak only in absolutes. They define their partners’ reality for them. Everyone just waits their own turn to say their own talking point.

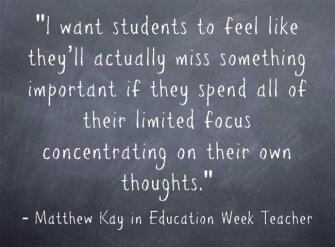

Not Light, But Fire describes methods that teachers might use to develop students’ listening patience. Perhaps my simplest suggestion is to normalize the celebration of students’ ideas. When a student shares an idea in our class, I try my best to pull a highlight. I then redirect this highlight to the rest of the class, offering it up as a scholarly contribution worthy to be reflected upon. I honor these contributions by asking incisive questions. I am effusive with praise, often asking a speaker’s classmates, “Did you hear what _____ said? Ya’ll better get that down (in their notebooks), it’s brilliant!” A few times a week, I make a point to lose my mind a bit - sprinting over to a kid to give them a high-five, or scrunching my face into what my students call my “funk face,” as if overwhelmed by their brilliance. It’s playful, but through the silliness students learn that it’s okay to acknowledge when peers have a good idea. And you don’t get to join the appreciation party unless you actually hear what peers say. I am often surprised how quickly this atmosphere of appreciation can take root. Students actually snap their fingers at good ideas, point to the speaker, nod, or whistle their approval. All of these behaviors I mimic and encourage. I want students to feel like they’ll actually miss something important if they spend all of their limited focus concentrating on their own thoughts.

LF: You offer some intriguing ideas on if and how teachers can offer their opinions on potentially “controversial” issues. Can you share a short summary or a few specific thoughts?

Matthew Kay:

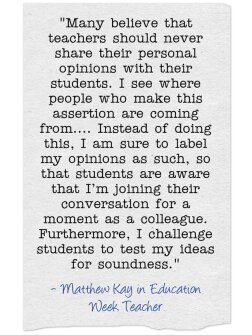

My book argues that we should make clear delineations between facts and our opinions, and be clear about how the former informs the latter. This fact/opinion distinction is especially important in these strange social and political times. Here, again, the adult world does not consistently model the best habits. It falls on us to model how scholars make up their minds about controversial topics, how to sift through all of the available information to see what holds water.

This stance, in and of itself, is controversial. Many believe that teachers should never share their personal opinions with their students. I see where people who make this assertion are coming from. Yet, when students ask a teacher’s opinion, they are often expressing a need, and to ignore it is to be paradoxically dismissive of their voices. Instead of doing this, I am sure to label my opinions as such, so that students are aware that I’m joining their conversation for a moment as a colleague. Furthermore, I challenge students to test my ideas for soundness. This hopefully models humility in the face of new ideas. When my execution is consistent, students tend to mimic this habit.

LF: I learned a lot from your chapter on the N-word. What are two-or-three of the most important points you would suggest that teachers keep in mind as they consider their own approach to this issue?

Matthew Kay:

I knew that that the N-word chapter would get a lot of attention - so much so that I am loath to isolate it. Pretty much my worst nightmare is teachers skipping immediately to that chapter and launching into a similar conversation with kids. None of Part 2’s conversations can work without establishing Part 1’s ecosystem. Throughout the book, I emphasize that there are no shortcuts to this work. In fact, I state plainly that I’d prefer teachers not lead the conversations at all if they are going to lead them haphazardly. The conversations described in the last 4 chapters, the N-word one especially, are neither paint-by-numbers nor plug-and-play. They are examples of me using the approaches laid out in the first 4 chapters to lead specific tough conversations, ones that were relevant to my students and crucial to understanding the texts I was teaching.

Imagine a hypothetical teacher who, after reading my N-word chapter in isolation, decides to launch into the topic before teaching Huckleberry Finn. Such a teacher might be aware of how often the book has been banned for Twain’s ceaseless use of the N-word. So, this teacher decides to prep his Huck Finn unit by forcing students to debate whether books with the N-word should be taught in classrooms. This teacher, thinking himself bold, would instead be guilty of ignoring more than a few of the suggestions of Chapter 4, where I stress the importance of establishing clear and meaningful purposes for each race conversation. Among other mistakes, this teacher is pushing students into a fraudulent debate - as he clearly intends to teach Huckleberry Finn anyway - regardless of whether the students deem it appropriate. He just wants to lead kids to his own conclusion. Such manipulation tends to be violently clear to students, and consistently damages relationships in the classroom.

But let’s say that a teacher is not approaching the conversation haphazardly, and she has done all of the reflection and building work of the first 4 chapters. And let’s say that her curriculum demands that students thoughtfully engage the N-word. Then I would only advise that she tread carefully, and to remain open to cultural perspectives that she might not have anticipated.

LF: If you had to tell a room of teachers three “universal” guidelines for them to have effective classroom discussions, what would they be?

Matthew Kay:

1)Chapter 2 asks teachers to reflect upon our interpersonal skills, a task that unfortunately is not often considered a part of our professional development. We are often especially sensitive about any gaps in our interpersonal skills, as they make up a great deal of our identity as teachers. We think that our responses to student contributions (and behavior) are appropriate. We think that the messages that we intended to communicate have actually been received. We modernize our curriculum and hone new pedagogical strategies, but we rarely dive into the most personal self-reflection: am I a good communicator? How can I get better at it?

Here, I would encourage teachers to not only consider the points mentioned in Chapter 2, but to stay plugged into the research about communicating effectively. For example, I finished Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow soon after handing in the final draft of my book - and his observations about how people (and, to my purposes, students) process information and make decisions were earth-shattering. I would have used Kahneman’s psychological and sociological lenses to add maybe 10 pages to my book! I’d encourage teachers to never stop thinking about how to be better communicators.

2) Chapter 3 discusses curriculum and conversational structures. My favorite point here was inspired by Jonathan Zimmerman and Emily Robertson’s The Case for Contention: Teaching Controversial Issues in American Schools. In it, they describe the importance of teaching our students deliberation. They say, “Effective deliberators should be able to construct sound arguments for their positions but should also be open to changing their views when confronted with better arguments.” From this point, I reason that teachers should ensure that their students are encouraged to acknowledge when someone else’s argument is better than theirs. This, like many stances I’ve mentioned, is almost never modeled in the adult world. Chapter 3 encourages teachers to re-examine their activities, like scholarly debates, looking for ways that students can spend as much time in reflection and acknowledgement as they do on the offensive.

3) Lastly, I would remind teachers to remain humble. Throughout Not Light, But Fire, I tried my best to share as many of my own missteps as possible. With each, I made clear what I learned, and how the moment made me a better discussion leader. I’ve not stopped making mistakes. Even last spring, soon after the final manuscript was handed in to my publisher, I made a pretty big mistake during a race conversation. Thankfully, because of all of my reflection work, I was able to notice the error quickly. I apologized to students over email, then in person the following day. We must approach race conversations with similar humility, not thinking ourselves too progressive, too kind, too thoughtful, too educated, or too earnest to make a mistake. We all make them, and students generally appreciate when we own them, apologize, and move forward with more awareness.

LF: Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you’d like to share?

Matthew Kay:

I hope that this book inspires people to build community with like-minded educators. We need a group of peers to be honest with us, to push us to see what we have not noticed, both in the world and in our practice. During this journey, we need to lift each other up. There are so many forces in this world that seem bent on isolating us, setting us in competition with each other, and ultimately destroying teachers’ confidence. Without confidence, it’s hard to lead meaningful race conversations.

It is so important that we share our best ideas within and among departments, to fight the temptation to be the one “cool” teacher who “gets it.” In fact, the best compliment that I have received about Not Light, But Fire is that its tone is “generous.” As a teacher, I have benefitted from the immense generosity of countless colleagues and mentors, who have inspired me to see more, to work both harder and smarter, to imagine greater possibilities for my students’ conversations. Not Light, But Fire is my attempt to follow their example.

LF: Thanks, Matthew!