Overall SAT scores for the class of 2008 were identical to those of last year’s class, it was announced last week, but that hasn’t dissuaded experts from sifting through the data for subtle shifts and hints of potential trends.

The College Board, the New York City-based nonprofit organization that owns the college-entrance exam, released data showing that last spring’s graduating class earned a mean composite score of 1511 on a scale of 600 to 2400.

That composite score was the same as the one earned by the class of 2007, which also posted scores identical to this year’s class on all three sections of the exam: 502 for the critical-reading section, 515 for the mathematics section, and 494 for the writing section. Each section has a minimum score of 200 and a maximum score of 800.

“We’re encouraged that the scores are staying relatively stable,” Laurence Bunin, the senior vice president of operations and general manager of the SAT program for the College Board, said in a conference call with reporters. When asked for an explanation of the flat scores, he said, “It’s very hard to say.”

The scores ended a two-year trend of slightly falling scores since 2006, the first year in which students took the retooled exam, which included the addition of a writing section. Still, SAT experts were cautious in their appraisal of the numbers.

Wait and See

“It’s certainly better to see scores flat rather than a decrease,” said David Silver, a senior researcher at the National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing, at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The fact that more students seem to be taking [the SAT], and the score’s staying steady, is encouraging. But I wouldn’t read too much into it.”

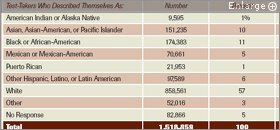

Mean scores for the 1.5 million members of the high school graduating class of 2008 who took the SAT exam varied by students’ self-reported race or ethnicity.

Source: College Board

Robert Schaeffer, a spokesman for the National Center for Fair & Open Testing, a Cambridge, Mass.-based testing-watchdog group that is often critical of the College Board, agreed.

“You don’t know about the trend until you see several years of data—we need to wait and watch whether this is an anomaly or a new trend,” he said.

In this year’s graduating high school class, 1.52 million students took the SAT—a 1.6 percent increase over last year’s class—but the significance of that growth can be a matter of interpretation.

Although the number of SAT-takers was at an all-time high in raw numbers of students, the proportion of graduating high school seniors who took the exam has been slowly falling since the graduating class of 2005—the last class to take the SAT before the College Board lengthened the exam with an essay-writing component and added Algebra 2-based questions to the math section, among other changes.

From its peak with the class of 2005, 48 percent of whom took the SAT, participation levels have slipped to 46 percent, the figure for the class of 2008.

At the same time, participation in the rival ACT exam, owned by the nonprofit Iowa City, Iowa-based test-maker ACT Inc., has been rising. Of the class of 2008, 43 percent of high school graduates took the ACT—an increase of 3 percentage points over the participation rate among the class of 2005.

Thanks in part to the addition of Michigan to the list of states requiring the ACT as part of their statewide assessment systems, the total number of students taking the exam was 9 percent higher among the class of 2008 than it was among the class of 2007. That one-year participation surge was larger than the last five years of SAT participation growth put together.

The SAT, which has long been dominant, still attracted about 97,000 more students than did the ACT among members of the class of 2008, but the gap has been closing in recent years.

“The SAT is losing popularity among college-bound seniors,” said Mr. Shaeffer, because of “the perception that the rival ACT is a more consumer-friendly exam.”

Mr. Bunin played down the ACT’s growth. “It doesn’t cause us to reevaluate the [SAT],” he said of the tightening competition. “We don’t do this as a horse race.”

Gender Gaps Persist

In line with previous graduating classes, gender gaps persisted on this year’s SAT. Despite narrowing score differences between men and women on some other standardized math exams in recent years, the mean math score on the SAT for men among this year’s graduating class was 533 out of a possible 800 points, 33 points higher than the mean score for women. That’s the smallest difference in years, but still substantial.

Female students continue to take the test in greater numbers than their male peers; in this year’s class, 54 percent of test-takers were female.

“There is certainly no clear explanation of why the male-female math gap has disappeared on most state tests but not on the SAT,” Jim Hull, the education policy analyst for the National School Boards Association in Alexandria, Va., said in an e-mail. “One reason that I heard is that a greater number of minority females than minority males take the SAT, which may suppress female scores. It also just may be because more females are going to college, so a greater variability of SAT/ACT [scores] is found for females.”

“There have traditionally been differences on how men and women—girls and boys—do” on different sections, Mr. Bunin said. He called the SAT “a fair test,” however.

Men also hold a long-standing but much-smaller edge on the critical-reading section: Among this year’s class, they had a mean score of 504 while female students averaged 500.

But in the three years the writing section has been administered, women have performed better than men. This year, the mean score for female test-takers was 501 on the writing section; male students managed only a mean score of 488.

The College Board calculates its SAT-score statistics using one test per student; no matter how many times a student takes the SAT, only his or her latest score is counted for the purposes of the College Board’s SAT report.