More schools are using credit-, debit-, and club-card rebate programs sponsored by big retail operations such as Target Inc. and Macy’s, or by restaurant chains, to help pay for sports uniforms, educational technology, field trips, and even facilities repairs.

The retail-rebate programs, in which parents earmark money from their purchases to go to their children’s schools, can be highly lucrative, and they’re supplementing or even supplanting such time-honored fund raisers as car washes and candy sales. And this new way of raising money has become increasingly important as state education budgets have tightened in recent years.

“It’s a [fund-raising] area that’s relatively new and emerging,” said Vincent L. Ferrandino, the executive director of the National Association of Elementary School Principals, which has 29,500 members and is based in Alexandria, Va. “There are still car washes and bake sales going on, … but the notion is that people are shopping and buying anyhow, so if they can designate a portion [of their purchase] for schools, then all the better.”

Read the accompanying business column,

But while some educators and parents say the rebate programs are a boon to schools, opponents of commercialism in education see the approach as yet another sneaky way that corporations are trying to make money from K-12 schools.

“It’s very troubling that we’re telling [parents] to shop to get their kids educated,” said Susan Linn, the associate director of Judge Baker’s Media Center, a child-research group affiliated with Harvard University, and the author of Consuming Kids: The Hostile Takeover of Childhood.

$100,000 a Year

Schools can receive hundreds to tens of thousands of dollars a year when parents or others shop at participating retailers. And the more they shop, the more money schools get.

Just ask Lisa Freeman. She’s the president of the Granada High School Supporters, a boosters club for the 2,100-student Granada High in Livermore, Calif., an affluent suburb 45 miles east of San Francisco.

The boosters club helps some of the school’s sports teams and student clubs raise money through eScrip Inc., a San Mateo, Calif.-based company that seeks to connect retailers and shoppers.

Students ask parents, relatives, teachers, and friends to register up to four of their grocery loyalty cards and up to seven of their credit or debit cards through a handwritten form or via eScrip.com.

When those people shop, a cashier swipes their cards through the cash register, which automatically gives 1 percent to 8 percent of the purchase back to the boosters club, which receives the money each month. The supermarket chain Safeway Inc. is one of the most-used eScrip-partnered merchants, Ms. Freeman said.

The Safeway program works on a graduated scale. A participating Safeway shopper who spends under $300 a month gives 1 percent of the amount to the designated school, according to company literature. If the shopper spends from $300 to $499.99, the first $300 generates a 1 percent revenue contribution to the school, and any amount above that generates 2 percent. The most Safeway gives back is 4 percent.

The average monthly amount a Granada High team or club gets through eScrip is $350, though some have raked in $1,300, while others took in far less, Ms. Freeman said.

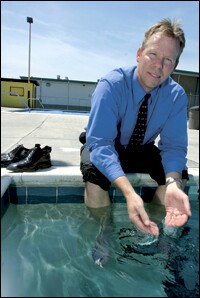

All told, the school receives about $100,000 a year through eScrip, said Chris Van Schaack, the principal of Granada High. Since the dot-com bubble burst in 1999 and state revenues plummeted, the extra cash has paid for school necessities, not luxuries, he said.

Some examples include fixing the pump and other equipment for the school swimming pool, refurbishing old band instruments, and dispensing fruit juice and breakfast bars to thousands of hungry students the morning they took the state’s standardized tests.

Mr. Van Schaack said he understands the concerns some people have about commercialism in schools. But the benefits far outweigh the drawbacks, he said.

“If this was a perfect society, then we wouldn’t have to do this,” he said. “But if it’s a choice of not having computers, then I’m willing to give.”

“This doesn’t require anybody to do anything they don’t already do,” Mr. Van Schaack added. “You would have bought those things anyway.”

‘Marketing Ploy’

Not everyone agrees.

Ms. Linn of Judge Baker’s Media Center argues, for instance, that the rebate programs put more pressure on people to spend money, and to spend it at certain places.

Plus, the success of the programs sends the message that adequate public funding of schools isn’t a necessity, she says.

“The more corporations leap in to fill the breach, the more people will think that we don’t need funding for public education,” Ms. Linn said.

“If corporations want to donate money to schools, then they should donate money to schools. Not use this marketing ploy,” she said.

Business has been good for eScrip Inc., which started up in 1999. The trend toward fund raising through shopping has allowed the company to grow from having just a handful of local merchants and schools in California to more than 200 retailers and 30,000 schools and churches nationwide. The number of families that have registered through eScrip now totals 1.5 million.

“People are willing to change their shopping patterns to benefit their children,” said Ian Diery, the chief executive officer of eScrip. “It puts empowerment in parents’ hands.”