The nation’s largest teachers’ union is pushing compulsory high school graduation as an important step toward reducing the number of dropouts.

The National Education Association released a 12-point plan at the National Press Club here last week for stemming a national dropout rate it says amounts to a crisis. The recommendations include such familiar prescriptions as universal preschool and more varied offerings for high schoolers, along with a proposal for states to make it illegal for students younger than 21 to leave school before getting a diploma.

Only one state, New Mexico, legally requires high school graduation. Seventeen states and the District of Columbia set the school-leaving age at 18, while the rest put it at 16 or 17, according to the NEA.

The union’s plan couples the proposed change in compulsory-schooling laws with a call to establish “high school graduation centers” for students 19 to 21, who would get teaching and counseling there tailored to their needs. To finance some of the changes, the union seeks $10 billion in federal spending over the next 10 years.

Many experts say that close to one-third of high school students do not graduate with their classes.

The plan comes as the 3.2 million-member NEA gears up for reauthorization of the 4½-year-old No Child Left Behind Act, which could take place as early as next year and is almost certain to mean some reshaping of the sweeping federal education law. The NEA, which was largely shut out of the creation of the measure, has likewise largely failed to turn policymakers or the public against it.

As a result, the union has been focusing more of its attention on preparing the broadest possible case for the changes it favors. In that campaign, high school improvement—including a reduction in the dropout rate—figures prominently, since that issue is high on many policymakers’ agenda for the reauthorization.

The NEA has also reorganized internally to better make its case, shifting its policy activities on student achievement and school improvement to a new department under Joel Packer, who continues to be the union’s lead lobbyist on the No Child Left Behind law.

“NEA wants to be more proactive,” Mr. Packer said. “As opposed to just criticizing, ... we want to say, ‘Here also is what we want.’ ”

Other moves include convening 22 of the union’s state affiliates in Washington next month to hear how the dropout plan can be furthered in state capitals and working on legislative strategies—state and federal—intended to address the dropout problem.

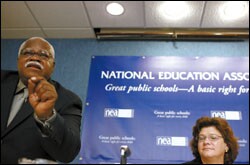

“We want to support states that are willing to make high school graduation compulsory,” said John I. Wilson, the NEA’s executive director.

Priorities Debated

But Dane Linn, the director of the education division of the National Governors Association’s Center for Best Practices, said such a change might be a hard sell to state governments. “I do think we need to raise the compulsory age to 18, but to raise it to 21, given our dropout rates, that would break the bank,” he said.

Still, Mr. Linn applauded the union for recognizing that different students need different paths to a diploma. “The idea that they would suggest that all students wouldn’t have to move through high school in the same time frame and do the same thing is positive,” he said.

Among other recommendations the NEA makes are: increase career-education and workforce-readiness programs; monitor students’ academic progress through a variety of measures; strengthen early-childhood education, along with ensuring solid content in elementary and middle schools; and give educators the training and resources they need to prevent dropouts.

Bethany M. Little of the Washington-based Alliance for Excellent Education, which advocates measures to help struggling students in secondary schools, also welcomed the union’s call for action on dropouts.

Given that the NEA represent “3 million teachers on the front lines of the battle, it’s hard to imagine winning the war without them,” said Ms. Little, the group’s vice president for policy and federal advocacy.

The union’s plan has some of the right elements, she said, citing personalized educations, improved data on dropouts, and a federal focus on high school graduation. But Ms. Little, too, had doubts about promoting compulsory graduation.

“It’s a very small part of solving the problem,” she said. “We really need to get at why kids are dropping out, and that’s because they are not engaged.”