Immigrants account for 18 percent of the early-childhood education workforce, a slightly higher percentage than are represented in the workforce at large, according to a new report by the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

On the one hand, the low bar for entry into many early-childhood care and education positions has been a boon to immigrant workers with little formal education or with degrees that do not translate in the American workforce, according to the April 28 report.

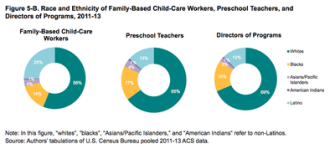

On the other hand, with a growing focus on raising the quality of early-childhood educator training in center-based public programs, many immigrants are relegated to the lowest-paying home-based child-care positions. Fully half of the immigrants in the early-child-care workforce work as private or home-based child-care workers, while only 29 percent of native-born early educators do.

Native-born workers in early-childhood education are twice as likely to be preschool teachers or center directors than immigrant workers, who are more likely to be assistant teachers or to care for children younger than 4 years old.

While about the same percentage of immigrant and native-born early-childhood educators have a bachelor’s degree (21 and 26 percent respectively) they are far more likely to have less than a high school diploma (25 and 5 percent respectively).

The pay picture is complex. While early-childhood educators are paid quite poorly in general, immigrants are paid more than their native-born peers in some cases. for example, immigrants with an associate’s degree or higher who are employed full-time (only half of the early-childhood workforce is full-time) make a few thousand dollars extra per year compared to their native-born peers. Though the report does not specify a reason for this, it could be that many immigrants speak a foreign language, a skill in much demand in preschools these days.

However, since so few immigrants have advanced degrees, the report points out that only a small percentage of immigrant workers stand to benefit from the slight earnings-advantage at the highest levels. Moreover, the trend toward requiring higher levels of education “may have the indirect result of pushing immigrant workers with less formal education out of the ECEC [early-childhood education and care] field, in turn diminishing the linguistic and cultural competence of the workforce overall,” according to the report.

"[Immigrant] and new workers will likely need assistance in gaining advanced training and credentials in order for the field to retain and build its linguistic and cultural competency skills,” the report recommends in its conclusion.

In addition to considering wide-ranging policy implications, the report also takes a detailed look at the population of children under age 6 with immigrant parents and breaks down data on parents and child-care workers by state. You can download the entire report here.

Graphics: Both graphics are borrowed from the Migration Policy Institute report, Immigrant and Refugee Workers in the Early Childhood Field: Taking a Closer Look.