The educational accountability movement’s keen focus on bringing all students to academic proficiency risks leaving behind a group of particularly promising students: high-achieving children from lower-income families, a new report contends.

The study analyzes national data to track the school performance of about 3.4 million K-12 children who come from households with incomes below the national median but score in the top quartile on nationally normed tests. It finds that they start school with weaker academic skills and are less likely to flourish over the years in school than their peers from better-off families.

Civic Enterprises llc, a Washington-based research and public-policy group, and the Lansdowne, Va.-based Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, which co-produced the “Achievement Trap” study, urged researchers and policymakers to better understand the dynamics that allow high-achieving, lower-income children to fall behind, and to focus concerted attention on ways to help them.

“By reversing the downward trajectory of their educational achievement, we will not only improve their lives but strengthen our nation by unleashing the potential of literally millions of young people who could be making great contributions to our communities and country,” the report says.

Link to NCLB

Read the related story,

The report’s Sept. 10 release coincided with testimony by one of its authors before the education committee of the U.S. House of Representatives on possible revisions to the No Child Left Behind Act. Joshua S. Wyner, the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation’s executive vice president, urged federal lawmakers to broaden the law’s focus so that schools are held accountable for improving the performance of higher-achieving as well as lower-achieving students.

Mr. Wyner said later he hopes the achievement patterns detailed in the report will help educators realize that highly capable students from lower-income homes need extra support to continue their success.

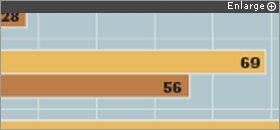

High-achieving students from lower-income families start school behind their peers, fall back during high school more often, and complete college and graduate school at lower rates than students from higher-income families.

SOURCE: Civic Enterprises LLC and Jack Kent Cooke Foundation

“Too many people believe that poor and underachieving are inextricably linked,” he said in an interview. “They say, ‘Why are you helping those [higher-achieving] kids? They’ve already made it. You should be helping the underperforming kids.’ But that’s a false choice. These high-performing kids from low-income backgrounds aren’t being served by our educational system either.”

The report says that such children enter school with a disadvantage that shows up in their national test scores. More than 70 percent of 1st graders who score in the top quartile are from higher-income families, and fewer than three in 10 are from lower-income families.

In the ensuing years, the higher-achieving lower-income children are more likely to lose ground, according to the study. For instance, 44 percent fall out of the top quartile in reading between the 1st and 5th grades, compared with 31 percent of high achievers whose family income is above the national median, which was $48,200 in 2006, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

‘Unrelenting Inequities’

They are also more likely to drop out of high school or not graduate on time than those from economically better-off families, the study found. The difference persists through college and graduate school, with lower-income students less likely to attend the most selective colleges or to graduate.

The report does offer some optimistic notes. Of the higher-achieving students, it says, 93 percent of those from lower-income families, and 97 percent of those from higher-income families, graduate from high school in four years. Those rates are much better than the 70 percent of all students on average who get their diplomas on time, according to researchers’ estimates.

But the data still show too many “unrelenting inequities” that harm the prospects of capable children from lower-income families, the authors say.

The data also suggest the distance still to be traveled in understanding and addressing the dynamics in racial achievement gaps.

Among lower-income students, Asians showed a significantly better chance of staying in the top quartile in math during high school than did other students, including whites. And African-American students were the least likely group to rise into that top tier in reading or math, the report said. Michelle M. Fine, a professor of social psychology and urban education at the City University of New York, said she welcomed the examination of how economic class can affect children’s education. But addressing the needs of all disadvantaged children, she said, entails a more nuanced examination of how race and class intersect to influence their performance.

“Something is clearly working for those lower-income Asian kids that isn’t working for the lower-income black kids,” she said, referring to the racial-performance breakdowns among lower-income students in the report. “A class-only analysis isn’t going to give us the whole picture.”

Solutions must go beyond the policy thrust advocated in the study, Ms. Fine said, to systemic improvements in districtwide school financing, equitable distribution of highly skilled teachers, and access to quality preschool. She also noted that the children discussed in the report make up 6 to 7 percent of the country’s K-12 students, and that the authors’ definition of “high achieving” was their performance on nationally normed tests.

She wondered how many more children from lower-income families could be viewed as high achieving—and in need of extra support—if their performance were based on multiple measures, such as a portfolio of their work, instead of a test score.