It’s a disturbing but increasingly consistent pattern: Fewer teachers of disadvantaged students or students of color get the top ratings on newly established teacher-evaluation systems.

The phenomenon is raising the pressing, delicate, and so far unanswered question: Is this a problem with bias in these new rating systems, or is it symptomatic of the fact that such students are less likely to have high-quality instruction?

We know, for instance, that things like observations by principals can reflect bias, rather than actual teaching performance. Yet we also know that disadvantaged students are less likely to have teachers capable of boosting their test scores and that black students are about four times more likely than white students to be located in schools with many uncertified teachers.

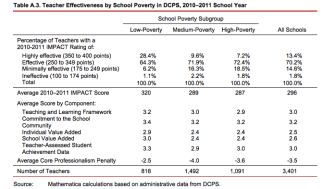

Let’s take a look at some of the newest data. Matthew Di Carlo, at the Shanker blog, has a nice analysis of the situation in the District of Columbia. He notes that teachers in low-poverty schools were far more likely to get the top scores on the district’s teacher-evaluation system, IMPACT, and on each of the measures making up the score: test-score results and observations.

The Pittsburgh teacher-evaluation program shows similar results, according to a recently released federal analysis of its technical properties. In that report, teachers of low-income and minority students tended to receive lower scores from principals conducting observations, and from surveys administered to students. Those teaching gifted students tended to get higher ratings. Here’s the technical data from the report. It’s represented in terms of correlations; note the negative direction for those teaching low-income or minority students.

There are a few takeaways from all of this:

- Critics have lambasted “value added” systems based on test scores as favoring teachers of better-performing students. But alternative measures, like observations and surveys, appear to be just as susceptible.

- It’s hard to know based on currently available data whether these patterns reflect flawed systems or a maldistribution of talent; in fact, it could be a combination of both—but as Di Carlo writes about D.C., “none of the possible explanations are particularly comforting.”

- Could the likelihood of lower scores discourage teachers from wanting to work in schools with more minority students or disadvantaged students?

All of this leaves the current state of teachers’ evaluations in some flux.

Researchers note that it’s impossible to have an evaluation system that is 100 percent always accurate—measurement is an imprecise science. One fix suggested by Brookings Institution researchers not long ago was to artificially inflate observation scores for teachers of low-income students, and other such statistical tweaks are possible. But such fixes could introduce worries about whether results are being doctored.

One thing’s for sure: We’re still in the learning phase on these new evaluation systems.