Despite widespread efforts to make evaluation systems more truthful, most teachers continue to receive good teacher-evaluation ratings—including a handful who probably don’t deserve them, according to a recently released working paper.

The findings largely mirror what Education Week reported in 2013, when the first results from systems retooled in the wake of the federal Race to the Top and No Child Left Behind waivers were released. States may have built a better mousetrap, but they haven’t changed the cultural norms at work in schools that can impact how principals and other evaluators assign ratings.

For the study, Matthew Kraft of Brown University and Allison Gilmour of Vanderbilt University collected data from 19 states with revamped teacher-evaluation systems. For a large, unnamed school district, they also collected surveys from evaluators in 2012-13 and 2013-14, asking them to guess the percentage of teachers that would fall into each rating category and comparing those figures that to how the teachers were actually rated. Finally, they interviewed some 24 principals.

Here are the top-line findings.

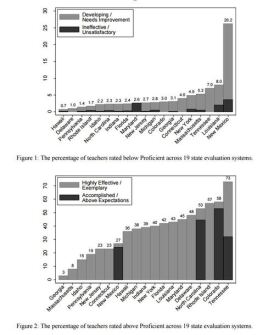

First, the percentage of teachers rated below proficient was generally quite low, ranging from below 1 percent to about 8 percent. New Mexico, with more than quarter of teachers falling into that category, was a major outlier—and has gotten a lot of pushback from its teachers for the tough grading. Interestingly, the range of performance at the top end was much more spread out. Very few teachers in Georgia or Massachusetts earned their state’s highest rating, but more than half did in North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, and Tennessee.

Second, the evaluators in the large school district were far more likely to perceive weaknesses in teachers than they were to actually give them a low score: In the 2012-13 school year, for instance, evaluators perceived that nearly 27 percent of teachers were below proficient, but only about 7 percent received that score.

In other words, the findings seem to indicate that “the Widget Effect” is alive and well. The name was coined by an influential 2009 paper by teacher-training group TNTP that suggested that teachers’ evaluations are inflated and teachers themselves aren’t given good feedback on how they’re actually doing.

In interviews, principals said they hesitated in giving poor ratings for fear it would demoralize a teacher even further. In some cases, they noted, it seemed easier to “counsel out” a teacher, giving her a good rating in exchange for her agreement to leave, than to follow the state’s lengthy, bureaucratic firing process or tussle with the teachers’ union.

A Washington Post story on the study noted that some outside researchers, briefed on the findings, expressed concern that some teachers’ ratings don’t really match their performance. Not only does it potentially mean poor performance is going unaddressed, it’s also an issue that hard to fix through administrative means.

They also noted, though, that we shouldn’t necessarily expect the same breakdown of ratings in each state. The incentives built into each state’s system—such as whether the evaluations are tied to job security or pay—likely effect how principals implement the systems, and how teachers respond to them.