My own contribution to the Hewlett Grantee Meeting was a

talk entitled “When Open Encounters Different Classrooms,” which is part of my

ongoing campaign to raise serious concerns about issues of equity and education

technology.

(Much more detailed papers, videos, and other descriptions

of this work can be found here)

The story goes something like this:

When we imagine an Open Educational Resources or education

technology ecosystem, one simple model is to assume that Builders make stuff,

put it on the Internet, and hope it gets to the brains of learners, either

directly or through facilitators like teachers, coaches and librarians.

We also assume that the net result of all this innovation is

increased learning: more neurons in young brains are rearranged in pro-social

ways.

This model might work for certain purposes (see the last

post for the problems with dividing Builders from Facilitators). But in my talk

I propose an important amendment to that model for thinking about ed tech in

the U.S. One of the signature feature of the U.S. education system is that it

is profoundly inequitable. - America is known as being middle of

the pack in OECD rankings and so forth but that’s only on average, our

wealthiest students are on par with the best students in the world, but our

educational outcomes for poor students in the U.S. are shameful.

So as I think about the model of OER systems in the United

States, I think about builders and the Internet, but on the other side of the Internet I

imagine two parallel sets of learners and facilitators in low-income and

high-income homes and schools. Now the hope, is that as builders create new OER

and edtech, it passes through a neo-liberal, democratizing Internet and can be

taken up by learners and facilitators in both kinds of environments

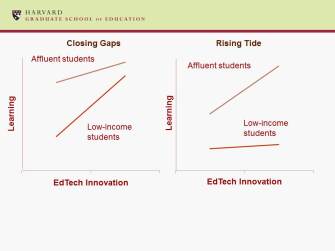

So if we amend our model of the OER system we also should

amend our model of learning. And my sense is that there are two kinds of

stories about how OER and education technology innovations are received in

schools serving different populations.

In one story, we imagine that we start with an initial

disparity in learning opportunities between wealthy and poor students caused by

an inequitable society. Wealthy students already have access to a wide variety

of proprietary resources, tools, platforms and so forth, and so OER and other

ed tech innovations disproportionately benefit low income students who now have

access to these free tools and resources. We can call this the closing gaps

scenario.

Another story we could tell, is that affluent schools have

much great human, social and technological capital than schools serving

low-income students. They have less test pressure, and their teachers have more

prep periods, fewer students, more curricular support, and better technological

infrastructure. Most new innovations, therefore, disproportionately benefit the

already advantaged. Technology acts as an accelerant to the underlying

inequities in schools. We might call this the rising tide scenario.

So which of these stories better represents reality? Well,

we don’t know for sure, but my research on wikis provides one perspective. In

my most recent study, I examined a random sample of wikis used in U.S., K-12 public

schools drawn from a population of nearly 200,000 wikis. I found that more

wikis are created in affluent schools than school serving low income students,

and wikis created in affluent schools are significantly more likely to provide

opportunities for students to develop 21st century skills and they

persist longer.

So with certainty in the case of wikis, these tools are

taken up in very different ways in different environments, and while wikis pass

from builders through the Internet into schools and homes in high income

neighborhoods, for a wide variety of reasons--technological, curricular,

pedagogical, and so forth--wikis aren’t taken up to the same degree in low

income neighborhoods.

In other words, the end result of an explosion of freely

available OER and education technology resources could be to widen the

opportunity gaps between wealthy and poor students.

So if we think that’s a problem, then we should not depend

on the Internet to be a democratizing, equalizing platform for distributing

learning tools and platforms. We need to think very carefully about how we can

design learning tools and distribution pathways that serve students with the

greatest needs.

Please follow me on Twitter at @bjfr and for more about my work, visit EdTechResearcher.org.