Corrected: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described research by Philip J. Cook and colleagues as involving comparisons of 6th graders’ behavior in middle schools and that of 6th graders attending K-8 schools.

When the mayor and public school officials in the District of Columbia unveiled plans last month for converting Washington’s middle and elementary schools to a pre-K-8 model, system leaders seemed confident the change would be good for students.

After all, the school system has plenty of company. Since the late 1990s, districts in a growing number of cities, including Baltimore, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, and New York, have taken steps to move middle-grades students back into elementary schools.

But research emerging from that recent wave of K-8 conversions, as well as other new studies, suggests that determining once and for all what kind of grade configurations are best for students is still a complicated and unsettled matter.

“I think K-8’s do have a definite advantage, but it isn’t as big as a lot of districts are assuming,” said Vaughan Byrnes, a researcher at the Center for Social Organization of Schools at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who has studied Philadelphia’s K-8 programs.

Apart from a handful of studies from the 1970s and early 1990s, the recent return to K-8 schools has spread largely without much rigorous research evidence to show that reconfiguring the middle grades will improve learning for all the students involved. As more and more districts embrace the idea, though, that picture is beginning to change.

One focus of much of that new scholarship has been the 167,000-student Philadelphia district, which has undertaken what is arguably one of the largest and longest-standing attempts to phase out middle schools in favor of the K-8 model.

But studies to date are giving that city’s effort mixed grades, with several showing that middle-level students in K-8 schools outperform their middle school counterparts on standardized tests and one finding no academic differences between students in either setting.

The latter study, published two years ago by researchers from Columbia University, concluded that, all things being equal, 8th graders in K-8 schools had no higher grade point averages and no fewer F’s or absences than their peers in middle schools.

Neighborhood’s Impact?

In their own study of Philadelphia’s initiative, Mr. Byrnes and his co-author, Allen Ruby, add yet another layer of complexity to that debate.

In a report published in November in the peer-reviewed American Journal of Education the researchers conclude that, while 8th graders in Philadelphia’s K-8 schools outperform their middle school counterparts on state reading and mathematics exams, the edge comes mostly from the district’s older, established K-8 schools—primarily because they serve students from more-advantaged neighborhoods.

Even though 8th graders in the newly converted schools had experienced a smoother school transition and smaller grade sizes than their middle school counterparts, they failed to significantly outscore them.

“What a lot of districts are doing now are eyeballing test scores and saying, ‘Wow, our K-8’s are doing better than middle schools,’ ” said Mr. Byrnes. “But if they dig a little deeper, they might see that a lot of their K-8’s are in better neighborhoods.”

Mr. Byrnes and Mr. Ruby arrived at that conclusion by analyzing test-score data for successive waves of 8th graders—41,000 students in all— moving through the school system between the 1990-2000 and 2003-04 school years.

Researchers who have looked at 8th graders’ test scores from more recent school years—2002-03 to 2005-06—detected the same pattern: Students in newly converted K-8’s did not significantly outpace those in middle schools or match the gains found in older K-8 schools.

Though not yet published, those findings suggest that “Philadelphia’s attempt to replicate the achievement success often found in the older generation of K-8 schools has not yet been entirely successful,” wrote one of those researchers, Douglas J. Mac Iver, in an e-mail to Education Week.

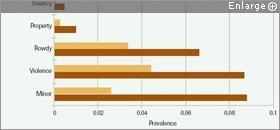

A Duke University analysis of disciplinary infractions in North Carolina public schools in the 2000-01 school year found lower incidences of a range of problematic behaviors among 6th graders in K-6 schools than those attending middle schools.

SOURCE: Duke University’s Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy

With his wife and co- researcher, Martha Abele Mac Iver, Mr. Mac Iver has been tracking academic progress in Philadelphia as part of a separate, larger study of that district’s reform undertakings. Both research scientists are colleagues of Mr. Byrnes at the Johns Hopkins center. Philadelphia school officials disagreed with the Mac Ivers’ conclusion, though. “I would not say the K-8’s have been effective in just the more affluent neighborhoods,” said Cassandra W. Jones, the district’s interim chief academic officer. “We’ve looked at it in old ones, new ones, everywhere, and we’re pleased with the results.”

Also, it still may be too soon to make any sweeping conclusions about the Philadelphia’s K-8 initiative, added David L. Hough, the dean of the education school at Missouri State University in Springfield and the director of that school’s institute for school improvement.

While some Philadelphia schools began converting to the K-8 model as early as the late 1990s, the shift has been gradual, with small cohorts of elementary schools adding one grade per year. The district middle school phaseout is expected to be completed, apart from a handful of schools, by next year.

“You really have to give a school four or five years of operation before you know if something is really going on in that environment,” said

Mr. Hough, who, since 2001, has been compiling a national database of schools moving to a K-8 or grades 1-8 model. Mr. Hough said his database now contains 1,759 schools in 49 districts and 27 states that have either adopted the K-8 or 1-8 model or plan to do it soon. Although he is in the midst of analyzing the data to determine where middle-grades students are better off, some of his findings so far comport with Philadelphia’s experience.

For instance, Mr. Hough has found that, as was the case in Philadelphia, the schools moving to a K-8 model in his database are those that are struggling academically, have lower-income students, and are located in inner cities. That all suggests, he said, that less-than-stellar academic outcomes in the early years of their transitions might not be unexpected.

Nonacademic Factors

What the Philadelphia studies don’t measure, though, are the nonacademic benefits, such as fewer behavioral problems, that educators and parents often cite as a reason for teaching middle-grades students in elementary schools. A study in the current issue of the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, which is also peer-reviewed, suggests, in fact, those kinds of improvements can be sizable.

For their study, researchers from Duke University’s Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy in Durham, N.C., plumbed a state database with records of disciplinary infractions incurred in North Carolina’s public schools during the 2000-01 school year.

Their findings suggest that 6th graders attending middle schools are twice as likely to be disciplined as 6th graders enrolled in K-6 schools. And the odds that a 6th grader will incur a drug infraction are 3.8 times higher for students attending middle schools.

“Middle schools tend to be more formal in the way they handle petty offenses by children and, quite possibly, more likely to write them up,” noted Philip J. Cook, the lead author of that report and a professor of public policy. “More concerning is the possibility that this reflected a real change in behaviors, and my best explanation for that is that it was simply the exposure to older adolescents.”

The researchers also analyzed scores from state-mandated end-of-course exams that all the students involved in the study took in grades 4-8. In part because middle schools in North Carolina tend to be located in suburban areas, the researchers found that the 4th and 5th graders who eventually went on to middle school had started out as a more advantaged group in terms of academic achievement and socioeconomic status. But the students lost their academic edge after they moved to middle school.

While Mr. Cook and his colleagues contend their research provides clear guidance on where to house 6th graders, the implications for the overall K-8 or K-6 model are unclear.

“As a school moves from a K-5 to K-6 configuration, 6th graders get one more year of a ‘childhood’ culture,” they write in their report. “But when a school moves from K-5 to K-8, it exposes all the younger ages to 7th and 8th graders who are entering adolescence.”

Whether the benefits to the 6th graders from attending a K-8 school will offset any potential harm to younger children is an open question, they said.