(This is the first post in a two-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

In what ways can reading support writing instruction?

It isn’t easy for educators to teach reading, and it isn’t easy for students to learn the skill, either. But, in the midst of that challenge, how can we also use instruction to help students become better writers, too?

This series is a companion to an earlier one which examined the opposite—how writing can explore reading instruction.

Today, Michelle Shory, Ed.S., Irina V. McGrath, Ph.D., Laura Robb, Lindsey Moses, and Laverne Bowers share their thoughts. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Michelle, Irina, and Laura on my BAM! Radio Show. You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Mentor texts

Michelle Shory, Ed.S., is a district instructional coach and Google Certified Trainer in the Jefferson County public schools, Louisville, Ky. She serves five high schools in the district. In addition to coaching, Michelle designs and implements professional learning experiences for teachers across the district. She is passionate about literacy and helped establish Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library in Louisville.

Irina V. McGrath, Ph.D., is a district instructional coach and Google Certified Trainer in the Jefferson County schools. She facilitates online and face-to-face. She is also a co-director of the Louisville Writing Project (LWP) and a University of Louisville adjunct who teaches literacy- and ESL-methods courses.

Michelle and Irina are passionate about good books, meaningful tech integration, andragogy, and classroom joy. They share resources on Twitter and here:

Reading is a complex process that involves 17 regions of the brain and is an essential skill that helps students expand vocabulary, improve memory, sharpen attention, and develop imagination. Among these and other benefits, scholars have long agreed that reading improves writing. According to Krashen (1984), writing competence develops from large amounts of self-motivated reading. English-learners who read for pleasure in English tend to be more proficient English writers (Janapoulos, 1986).

Quantity and Variety Matter

Constant exposure to various literary and informational texts allows ELLs to deepen their understanding of each type of writing and develop their own style. In his paper “We Learn to Write by Reading, but Writing Can Make You Smarter,” Krashen (1993) wrote, “We acquire writing style, the special language of writing, by reading” (p. 27). Students who read more tend to use more complex sentence structures and vocabulary words and their writing contains features of the texts they read (Eckhoff, 1983).

Improving Quality With Mentor Texts

One of the most common practices of using reading as a step to better writing is mentor texts. The National Writing Project (NWP), a professional-development network that serves teachers of writing of all grade levels, defines mentor texts as “pieces of literature that you—both teacher and student—can return to and reread for many different purposes. They are texts to be studied and imitated. ...” Mentor texts serve as examples of good writing for English-learners. When teachers use them in the classroom, students’ quality of writing improves (Corden, 2007). Steps in teaching with mentor texts include:

- Selecting an appropriate mentor text

- Reading and discussing it

- Delving deeper into the content by focusing on details

- Analyzing author’s craft

- Selecting a writing skill to focus on

- Using mentor text as an example for own writing

Additional Considerations, Especially for ELs

When selecting mentor texts, be mindful of text complexity. Students must have a complete understanding of the text if they are going to analyze and appreciate an author’s moves. Also consider using diverse texts that provide windows or mirrors for ELLs. This concept, first introduced by Emily Style (1988), defines windows as texts that offer insight into the cultural experiences of others, while mirrors are works that reflect a student’s own cultural experiences.

By making time for English-learners to read for pleasure and by providing comprehensible mentor texts worthy of study, writing skills can flourish.

“Reading informs writing!”

Author, teacher, coach, and speaker, Laura Robb has worked with children and teachers for more than 40 years. At present, she works at Daniel Morgan Intermediate School in Winchester, Va., training 5th and 6th grade teachers and teaching children who read four to five years below grade level. Author of more than 30 books on literacy, Robb co-authors therobbreviewblog.com with her son, Evan. In addition, Robb speaks at national and state conferences and trains teachers in schools in the U.S. Follow her on twitter @LRobbTeacher:

Recently, I presented a series of writing workshops on memoir for middle school ELA teachers. Teachers read short memoirs by Ralph Fletcher from Marshfield Dreams as well as “Eleven” by Sandra Cisneros, and excerpts from Tis by Frank McCourt. First, we read and enjoyed each piece, but then we transformed them into mentor texts, reading each one with a writer’s eye to learn what made these selections compelling and memorable. Teachers’ reading and discussions led them to an understanding of memoir that in turn enabled them to develop these guidelines for writing a short one:

Focus on one significant event—hopefully, one that touched readers’ hearts.

Help readers step into your shoes and feel your emotions.

Use elements of fiction.

Show with dialogue, inner thoughts, actions.

Let dialogue move the story forward (like Fletcher did in “Funeral”).

Help readers hear your voice.

Make the memoir an emotional experience.

As teachers planned and drafted a short memoir, they experienced the process of hearing their memoir by reading it out loud, revising, conferring, more revision, editing for word choice, and including powerful images. By the end of our fifth meeting, teachers understood that writing takes time, and it helps to let the memoir cool—not read it for a few days—then return to it to revise again.

**************

Fast-forward to a few weeks after the workshop on memoir had ended. I’m in a middle school coaching two teachers. Classes are changing, and I’m walking down the hall when I see a teacher who was in the memoir workshop trying to get my attention. She weaves through the crowd of boisterous, energetic students, waving a stack of papers and shouts, “I need to show these to you!” as she ducks into her classroom. I follow, wondering, about the papers.

“I gave my students guidelines for a memoir and then told them to write one. Here read them,” she said, thrusting them into my hands. It felt as if she were telepathing this message to me: I worked hard in your class, and it did nothing for my students.

Trying to remain calm, I read several very short pieces. She was spot-on. Students wrote a few sentences telling their memory. “Did you use mentor texts with students so they could study outstanding memoirs?” I whispered.

“Oh, I left that out. We didn’t have time to do all of that.”

I wanted to cry. I wanted to shout that writers need time; writers need to read memoirs to understand the genre. But I squashed those negative impulses and gently talked to her. We agreed that she would return the writing to students ungraded, explain that they would read and study some memoirs, set their own memoir-writing guidelines, and then start planning and drafting. Fortunately, the second semester would start the following week, and she could give students the gift of time to read and study mentor texts.

I promised to check in with her frequently; I told her to email me if she had any questions. I encouraged her to invite students to learn from some of the mentor texts we studied. She promised to stay in touch and ask questions.

By rushing to fit in memoir writing during the last week of a semester, this teacher omitted a critical learning piece: reading to learn what outstanding writers of memoir do. I’ll end with the advice my editor gave me when I wanted to write a biography for young children: Read 50 biographies and learn something from each one. Yes, reading informs writing!

Literature Cited

Cisnerso, S. (1992). “Eleven,” In Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Fletcher, R. (2012). Marshfield Dreams: When I Was a Kid. New York, NY: Square Fish.

McCourt, F. (2000). Tis: A Memoir. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

A step-by-step process

Lindsey Moses is an associate professor and program coordinator of the M.A. in literacy education at Arizona State University. She is an author and consultant who works with educators across the country and internationally to support authentic language and literacy experiences in diverse educational settings. Lindsey has taken all the photos contained in this response.

Reading and writing are inextricably linked, yet these “subjects” are often taught separately in schools. Using reading to support writing and writing to support reading provides extensive opportunities for students to deepen their literacy experiences. In all of my thinking about supporting elementary readers and writers, I try to ask myself ... what do readers and writers do (in the world outside of school)? In what ways might I introduce, scaffold, and support those practices for my students?

As a writer, the first step of my process is usually reading ... for new content knowledge, for ideas, for support/collaborating citations from content experts, for structure ideas, for voice and craft ideas, basically, just a ton of reading and thinking. I try to “read like a writer” to identify content and aspects of writing that appeal to me and can be applied to my future writing. I identify these aspects, think about their purpose, and identify ways I might take them up, adjust them, and use them to serve my own writing purposes. Based on this, I have been collaborating with teachers to do the same in classrooms—use reading to support writing instruction. Two easy ways to approach this practice of reading supporting writing include author studies and genre studies. Studying an author and/or specific genre allows readers to think deeply about the structures, characteristics, and craft writing moves. Here are some initial steps we use to get students reading like writers.

Flood the classroom with books that are representative of the unit focus (author study or genre study).

Give students time to browse, read, and explore multiple representative books.

Ask students to document “noticings” (patterns, characteristics, text features, structures, voice, content, similarities/differences to other texts, etc.).

Ask students to explore books in partners or small groups and discuss noticings.

Discuss noticings as a class—generate an anchor chart and/or reference sheet that includes noticings and purpose as age appropriate. (See Comics Features/Purpose Anchor chart below.)

Ask students to revisit texts with partners and analyze for the identified characteristics/noticings/purposes.

- Encourage students to use aspects of the genre or author’s craft in their own writing to serve their own purposes.

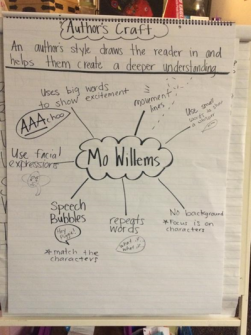

Below I share examples of what this looked like in a 1st grade and a 4th grade classroom. In Meridith Ogden’s 1st grade classroom, we studied Mo Willems and talked extensively about his craft. This involved read-alouds, partner reading, small-group experiences, anchor-chart creation, and attempts at using author’s craft in their writing:

Author’s Craft Anchor Chart

Small-Group Noticings and Discussion

Some students took up one or two small aspects of his craft, such as movement lines and speech bubbles, but others studied his work deeply and managed to integrate not only the concrete aspects we identified in the anchor chart but also took up his structure, tone, and voice.

In Sean Conway’s 4th grade class, we flooded the classroom with comics and graphic novels and asked students to explore features they noticed and discuss the purpose. In the pictures below, you can see the exploration and class anchor-chart creation:

Students then used these reading and analysis experiences to inform their multimodal comic compositions. Their writing included all the comic features explored and documented by the class in addition to features they independently took up from their own reading and partner discussions, like the close-ups and character perspectives seen in the students’ writing below:

Close-Up

Helping students notice, think, and discuss author’s craft, structure, features, genre characteristics, etc., allows students to make purposeful choices about writing. Students always exceed our goals for analyzing writing and then appropriating the practices and moves of authors into their own work. The key here is that it has to be purposeful and driven by author choice. We never tell students they HAVE to include all of the features or a specific number of features—author authority is a priority for us. Ultimately, the goal is that students can use reading to inform authorial decisions in all aspects of their writing.

“Reading and writing have a cause and effect relationship”

Laverne Bowers is a 4th grade teacher at Gadsden Elementary School in Georgia’s Savannah Chatham County school district, where she was 2018-19 Teacher of the Year. Bowers has created a cooperative, caring community of learners in the classroom and models the importance of mutual respect and cooperation among all community members. Her educational philosophy is that each child can learn with sufficient support, interest, and path of opportunity:

One can claim that reading and writing have a cause and effect relationship. When students write, they use their personal experience, background knowledge, and additional knowledge acquired through reading. As an educator, I expect to see evidence of students’ reading comprehension and overall knowledge gained from reading assignments presented in the form of composed essays, poems, commentaries, stories, and other written responses. Good reading practices can lead to effective writing, and students who begin as good readers can be taught to become good writers.

Reading is foundational for writing because it serves as an example of what good writing should resemble. The response to literature, the language of the text, point of view, and figurative language ... all of these skills and strategies are learned during reading. As a result, students can use their writing skills to respond to discussion questions about what they have been taught.

In order to become a good reader, one must read frequently. The challenge is for educators to create a literary environment that attracts enthusiastic and reluctant readers alike. Here are some of the strategies I use in my classroom to engage and support struggling readers:

- Provide text that appeals to the reader’s interest

- Give different choices of texts to read (textbooks, journals, chapter books, short passages)

- Make reading relevant

- Use video presentations (Flocabulary.com, Brain Pop, YouTube videos)

- Model through a read-aloud

- Try guided reading, using leveled text

Regardless of which strategy you choose, the teacher’s job is to help the student successfully master reading in order to successfully write. Writing instruction may also include the following components:

- Using mentor text (a published piece that serves as a writing example)

- Modeling (brainstorming, writing plans, making words, blending sounds)

- Prompt writing (writing practice, using graphic organizers)

- Free writing (demonstrating writing fluency)

- Project art (allow students to respond to visuals)

- Play music (allow students to respond to audibles)

- Integrating vocabulary (using new vocabulary in writing)

- Using a writing rubric (introducing the criteria used for writing)

- Conferences (teacher and/or peer feedback)

In my class, we use the Ready Reading and Ready Writing textbooks, which are aligned with the standard-based protocol and state standards for my grade level. Considering the question about how reading supports writing instruction, I let it play out in my classroom exactly like this: I use Ready Reading as the springboard for Ready Writing. With scaffolding, prompting, and suggestions generated from the online program (i-Ready, an interactive piece that proved to be the most instrumental teaching tool for my students), students were able to comprehend more efficiently, as they were able to place their thoughts more effectively in writing.

Whatever your resources, the goals should be to make sure students have relevant passages to read, reading materials with appropriate rigor, and a variety of writing activities. My goal this year is to continue to show students the significance of the relationship between reading and writing. If I want to measure student knowledge, I will give students the opportunity to demonstrate it in writing. Reading is one of the fundamental components of building a successful writer, and by preparing both reading and writing lessons in an interesting, integrated way, we promote learning and ensure that reading and writing are not taught in isolation.

Thanks to Michelle, Irina, Laura, Lindsey, and Laverne for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And if you missed any of the highlights from the first eight years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. The list doesn’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Best Ways to Begin the School Year

Best Ways to End the School Year

Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

Teaching English-Language Learners

Entering the Teaching Profession

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column.

Look for Part Two in a few days.