This post is by Katie Shenk, Lead Curriculum Designer at EL Education

In Annie Holyfield’s primary classroom at Joe Shoemaker Elementary School in Denver, Colorado, kindergarten students huddle together to create an imaginary rainstorm with their bodies. “Clap your hands again, a bit more loudly. Now slap your thighs with both hands and stomp your feet!” The young students delight in this playful activity that engages their bodies and brains. For the past six weeks, Holyfield’s students have been studying the weather through one of EL Education’s open-access English Language Arts curriculum modules: “Learning Through Science and Story: Weather Wonders.” Throughout this investigation, these young meteorologists have conducted scientific investigations, participated in structured conversations, sung songs and read poetry, and engaged in close read-alouds of literature and informational texts about weather. They will soon showcase their deep knowledge by writing their own fictional weather stories, a la Ezra Jack Keats’ The Snowy Day. Because they have read, thought, talked about, and played with meaningful content, students are better prepared to create high-quality pieces of writing. Even while they are meeting new standards for primary grades literacy, they are also excited about weather and eager to share their learning. Let’s take a closer look at the progression from reading to writing in action with primary learners.

Young Children Love to Get Close: Deep Read-Alouds

Creating an evidence-based reading culture in primary classrooms might seem both unnecessary and impossible. However, by adapting the techniques of close reading to reading aloud complex texts, and teaching students to engage their ears and brains simultaneously, even young students can learn to support their written ideas with text-based evidence.

In Sarah Metz’s class at Explore Elementary in Thornton, Colorado, for example, kindergarten students participate in a close read-aloud of Come On, Rain! By Karen Hesse. For students, close read-aloud experiences feel much like play, but they are actually engaging in important and hard work. Students’ responses to text-based questions, movement activities, and vocabulary practice serve as pre-writing experiences to help students rehearse for future writing. As students build their world and word knowledge by interacting with a rich text, they are also absorbing concepts and language they will later use in their own writing.

Let’s Talk About It!

But these experiences alone won’t suffice; young learners need time to talk about their understanding. Put simply, talk is the foundation of literacy. This should come as no surprise to educators of primary students, who know that students listen and speak well before they can read or write.

The power of talk does not diminish once students enter school. Young students need, and deserve, abundant time to orally share their a-has, questions, and musings with peers. However, rich conversations don’t often happen by happenstance. Teachers must to be intentional about creating the systems, structures, and routines that foster rich discourse. Conversational protocols that build rigor and equitable engagement, like Back-to-Back and Face-to-Face or Think-Pair-Share, are commonly used in EL Education classrooms.

Conversation protocols support primary students in multiple ways: they cultivate students’ listening and speaking skills, help deepen their content knowledge as they interact with peers, and empower students to use their voices as a vehicle for showing what they know and what they’re still wondering. Talk is also an essential scaffold for quality writing. When students talk about what they know before they write, they solidify their understanding of the content about which they plan to write. Primary teachers say to their students: “If you can say it, you can write it.” It’s imperative that students have the time, space and guidance to “say it” loudly and clearly.

Writing to Show Understanding

Once students have built content knowledge and vocabulary through reading, thinking, and talking, they are primed to show and deepen their understanding through writing.

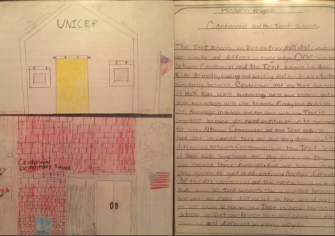

This is precisely what the 2nd graders in Kate Reid’s class at Centennial Elementary School in Denver, Colorado, did following an in-depth study of schools around the world. Students expanded their literacy and citizenship skills while reading a variety of texts about schools. They gathered information through research reading, participated in collaborative conversations, used graphic organizers to synthesize their research, and engaged in mini cycles of drafting, revising, and editing portions of their text. Then they applied their learning to produce informational writing, like the piece below, which explains what makes school important and compares and contrasts Centennial with tent schools in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

High quality writing is abundant throughout all the grades at Centennial and is showcased on the school’s high-quality work website. Improvements in students’ writing at Centennial are backed up by strong reading scores. In addition, students’ engagement in an authentic writing process enables them to learn skills and a mindset that they will continue to employ to craft future high-quality work.

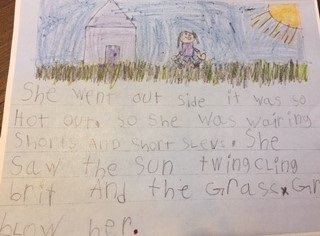

Teach Students to Critique and Revise for Excellence

For a window into that process, let’s re-visit Holyfield’s primary students as they write their weather stories. Students have begun to draft their stories, keeping in mind criteria for quality that they’ve generated collaboratively after looking at models of similar stories. Along the way, they will give and receive feedback in bite-sized pieces throughout the writing process. Each time they look at a partner’s work, Holyfield reminds students, “When we give feedback to someone on their writing (that they have worked hard on), it is important to be kind and helpful at the same time. We want to give feedback to help our partner improve his or her writing, but that feedback should also not hurt our partner’s feelings.” Holyfield provides sentence frames to support students’ feedback language: “I notice ______” “I like how you ________” and “Would you consider____?” Students then form partnerships and practice giving kind, specific, and helpful feedback aligned to the criteria for quality weather stories. Afterwards, they debrief the feedback process and set goals for the next round. This feedback process continues throughout the writing project and students’ ability to give and receive feedback sharpens with each try.

Because Holyfield has afforded her students the time and tools to read, think, talk, and write about meaningful content, they beam with pride during their celebration of learning where they showcase their weather stories for visitors. Like students at Centennial, these primary learners crave independence and mastery. Giving them multiple opportunities to build knowledge and share their expertise through high quality reading and writing experiences satisfies that craving. It also builds their competence and confidence in learning deeply.

Photo Credit: Joe Shoemaker Elementary School

Photo Credit: Centennial Elementary School