A school district in San Diego County struck just the right note when it started mariachi classes four years ago.

Mark Fogelquist is a witness to the power of mariachi.

Back in the mid-1990s, the former professional mariachi, then a bilingual educator for the Wenatchee, Wash., schools, persuaded his administrators to let him start a student mariachi band.

Out of the 47 newly arrived Mexican youths who signed up for the elective, only one had ever picked up an instrument.

“I hammered away with those kids,” says Fogelquist, “but the enthusiasm was there. And it was their thing. They had heard the music.”

Over two months, Fogelquist, the grandson of Danish and Swedish immigrants who has embraced Mexican culture, taught the students two tunes. Then, at a school meeting, which usually drew a dozen or so Spanish-speaking parents exhausted from working in the nearby apple orchards or fruit-packing houses, 100 showed up to watch the band.

"¡Otra! Otra! [Another one!]” the parents, rising to their feet and applauding, cried out after the students played the two tunes—their entire repertoire.

Though the youngsters couldn’t comply with an encore, they returned to their music classes inspired to work even harder. In the long run, the Wenatchee group twice won competitions for being the best student mariachi band in the United States.

Now, Fogelquist is striving to generate that same level of motivation in the Sweetwater Union High School District, based here in southern San Diego County, where administrators recruited him last school year to teach mariachi full time.

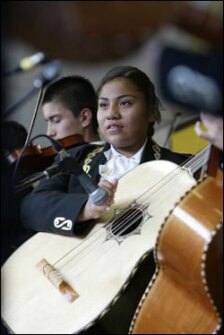

|

José Salinas, a native of Mexico and a professional musician, leads a mariachi class at Montgomery Middle School. |

Located eight miles from the U.S.-Mexican border, Sweetwater is one of a growing number of districts using mariachi—the music of celebrations and sad occasions in Mexico—as a way to engage Hispanic youths in school. With mariachi classes in 10 of its 36 schools and nine full-time mariachi teachers on staff, Sweetwater runs one of the largest school mariachi programs in the country, involving about 600 students. District officials view mariachi as one of many electives and extracurricular activities that capture adolescents’ interests and help deter them from dropping out of school.

Sweetwater’s dropout rate, in fact, is exceedingly low, especially considering that more than two-thirds of its 37,900 students are Hispanic—a segment of the population that nationally is at great risk of dropping out of school. The district has an annual dropout rate of 1.3 percent for all students and 1.9 percent for Hispanics in grades 7-12, far lower than for Hispanic students in the United States as a whole.

Sweetwater modeled its mariachi program after that of Irving Middle School in the San Antonio schools. A retired music teacher from the 57,600-student Texas district, Belle A. Ortiz, says she started the first mariachi elective in the nation in a San Antonio high school in 1970.

Dozens of districts in the Southwest have followed suit. And more continue to give the elective a try. The Orange Unified School District in California, for example, is poised to duplicate Sweetwater’s mariachi program and curriculum in two middle schools next fall.

“In the U.S., these groups have just blossomed as a result of trying to preserve the cultural roots of the family,” says Gilberto D. Soto, the chairman of the fine- and performing-arts department at Texas A&M International University in Laredo, which hosts a mariachi festival for about 35 Texas middle and high schools each year. Ironically, he notes, mariachi groups are practically nonexistent in Mexican high schools.

Mariachi is “another room in the musical house that people can enter,” says William A. Virchis, the director of visual and performing arts for the Sweetwater district. “We’re not building mariachis to play in restaurants,” he says. “We’re building musicians to play for life.”

Most mariachi students in the Sweetwater district were born in the United States and have parents who emigrated from Mexico. Others are of Chinese, Filipino, or other ethnic lineage and simply like the music.

Like mariachi bands in Mexico, the student bands use voice, trumpets, violins, guitars, and two guitar-like instruments called the vihuela and guitarrón.

“I can spend the whole day in my room playing and singing,” says 15-year-old Linda Uhila, a trumpet player in the most advanced mariachi ensemble at Chula Vista High School. Uhila, whose long black hair is wound into a neat bun and whose face is framed with large, silver hoop earrings, began taking mariachi classes with the trumpet in 7th grade at Montgomery Middle School after having played the violin in an orchestra program in 6th grade. She says she was attracted to mariachi because “it was something different and part of my background.” Her maternal grandparents are natives of Mexico.

|

Christian Gonzalez plays the harp in Chula Vista High School’s top Mariachi ensemble. The 17-year-old, who is partially blind and deaf, says, “This music is filled with messages of love and life.” |

Now in 10th grade, Uhila plans to major in music in college, with a focus on mariachi.

While students such as Uhila view their mariachi elective as a serious interest, many of their peers see it as a pleasurable diversion.

Mariachi class “makes me want to go to school more because I have something fun to do,” says Jesse Torres, an 8th grader who plays the trumpet in a mariachi group at Montgomery Middle School. At home, he says, he practices only “once in a while.”

In a hand poll, about two-thirds of the 32 beginning-violin students in mariachi classes at Montgomery acknowledge that their participation in the classes has increased their interest in school.

Keith R. Ballard, a former music teacher who is now a public relations officer for the district, started mariachi as a formal class four years ago after a school board member endorsed his idea. Before the start-up, Ballard says, some people feared that the mariachi elective would draw students away from traditional music programs.

He and other district officials now say that mariachi instead seems mostly to have attracted students—primarily Hispanics—who hadn’t yet gotten involved in a school music program.

At Montgomery, only seven of the 32 beginning-violin students say they had played a musical instrument before signing up for mariachi class. All but four of the beginners are Latinos.

The addition of mariachi hasn’t cut into other music programs, observes Fred Marx, Montgomery’s band director. “There is plenty of room for both programs to flourish,” he says.

But, he adds, the mariachi program has created some resentment among teachers of the traditional music electives. One reason, he says, is that the district has tended to hire noncertified teachers for mariachi, while most of the other music teachers are licensed. Three of the district’s nine full-time mariachi teachers are certified.

Also, Mr. Marx asserts that the district spends more per pupil on mariachi than it does on traditional programs because mariachi classes tend to be smaller than the others.

Sweetwater spends about $150,000, plus the cost of a teacher’s salary, to get the mariachi elective operational at a high school and the middle school that feeds into it, according to Ballard.

The Sweetwater district has supported Ballard in his recruitment of mariachi teachers who are top musicians, not people who necessarily have a college education or teaching credentials.

José Salinas, a native of Mexico who studied classical violin and performed in mariachi bands for 40 years, is one of them. He says he’s enjoyed making the career switch to public schools, although he doesn’t relish dealing with the “sometimes disrespectful” behavior of some students.

|

Skirts fly as Montgomery High School students perform. |

He, on the other hand, treats his students with courtesy—"Quiet, please,” he says frequently—and seems to have won the respect of many through his demonstration of musical skill.

While the students learn mariachi tunes, they also learn the basics of playing an instrument and reading music that can be applied to other forms of music. The district put a mariachi curriculum in place this school year.

|

|

In Salinas’ beginning-violin class at Montgomery Middle School, students struggle through the “Can Can” and “Cielito Lindo” while Salinas gently chides them, “Sit up straight. Use your full bow.” When the students play, the tunes are recognizable, but their music has poor intonation.

Salinas’ advanced-violin students, however, produce music that pleases the ear. His instruction is much more fine-tuned.

“Think of fiesta [and] horses,” he tells them. On the second try, their notes are fuller. “Your sound is nice and clear,” he tells one girl, imitating her tentative notes with his own bow, “but for this kind of music, you have to be more aggressive.”

Many mariachi students in Sweetwater have already tasted the rewards of performing. In past school years, Montgomery Middle’s mariachi ensemble—Mariachi Griego—has played for then-President Clinton, George W. Bush during his presidential campaign, and U.S. Secretary of Education Rod Paige. The Mariachi Chula Vista ensemble, directed by Fogelquist, has performed 40 times already this school year. The Montgomery High Mariachi Azteca, directed by Guadalupe Gonzalez, also gets regular gigs at community events.

A number of the students in the top-performing mariachi groups say that being part of the group has motivated them to improve their grades. “To perform with mariachi, you have to have a 2.0 grade point average,” says Ivan Villarreal, a 10th grader who plays violin in the Chula Vista ensemble. “That made me think more about doing well in school. Before, I used to slack off.”

Just as mariachi has transformed some youths’ lives, the teenagers are also transforming mariachi.

“I was used to seeing older men playing mariachi,” says Uhila, the trumpet player with Chula Vista’s top ensemble. “I heard mariachi on the radio. I never thought I’d be playing it.”

Now, she’s proud to be breaking into a male-dominated form of music.

|

Eunice Aparicio, 14, first became interested in the guitarrón, typically played by males, when she was 7. |

Eunice Aparicio, a 9th grader who plays the guitarrón with Montgomery High’s Mariachi Azteca, said she feels the same way. Her director, Gonzalez, observes that even among the limited number of female professional mariachis, few play the guitarrón.

Along with the vihuela, a small round-backed guitar, the guitarrón distinguishes mariachi from other Latin music. It looks like an oversize guitar, but is plucked instead of strummed and establishes the bass beat for a mariachi group.

“If the guitarrón is off,” Aparicio points out, “the whole thing is off.” Her tone of voice indicates that she takes pains to ensure the guitarrón is not “off.”

Despite the performing experience of the Mariachi Azteca, a recent engagement at a city festival starts out rough. The young mariachis arrive on stage five minutes late because they waited for their student soloist to show up before boarding a school bus to get there. As it turns out, the soloist wasn’t able to leave her part-time job at a pancake house on time and drives directly to the performance. She is confused, though, about the location and arrives, flustered, only after the show is over.

A couple of the group’s initial songs lack energy, and the musicians look solemn.

Gonzalez, the group’s director, fills in for the absent female vocalist with a rich, operatic-style tenor.

The performance picks up energy, and the audience of about 50 responds.

A woman with long, curly hair croons the words of one song, along with the band, to her infant. An older couple dance swing steps on the sidewalk with another tune.

The show includes slow-paced tunes, in which the violins whine, as well as pieces with a quick tempo in which fingers fly on vihuelas creating a beat that makes the audience want to dance.

The performance ends on a strong note with a lively rendition of a mariachi classic, “La Negra.”

The audience applauds; some people call out, “Otra! Otra!”

These youngsters have an encore in store.