A new report by the Learning Policy Institute paints a bleak picture of teacher workforce trends in California, warning of “severe consequences” to special education, math, science, and bilingual education.

The state has wrestled with teacher shortages for some time now, and the California-based think tank says that districts have responded to the shortages by hiring underprepared teachers, relying on substitute teachers, and assigning teachers out of their fields of preparation. This is disproportionately happening in schools that serve the most vulnerable students, the report found through analyzing data from California government sources.

Teachers hired with “substandard credentials"—meaning emergency permits that allow people who have not completed a teacher-prep program to teach for one year, intern credentials that allow people to teach while still taking courses, or permits that allow credentialed teachers to teach outside of their subject areas—are twice as likely to teach in high-poverty schools than in low-poverty schools and three times more likely to teach in high-minority schools than in low-minority schools.

The study points to research that shows that underprepared teachers depress student achievement and have higher attrition rates.

More special education teachers are entering the classroom on substandard credentials than are entering with full teaching credentials, LPI found. Just 36 percent of special education teachers in 2015-16 were credentialed, and the rest—more than 4,000 teachers—entered the field as interns or with emergency permits or waivers.

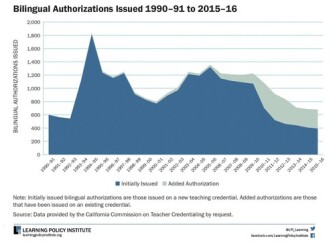

And California may be unprepared to meet an increasing demand for bilingual teachers, LPI predicts. In November, California voters decided to repeal English-only instruction, so now schools and families can seek bilingual education (and 1 in 5 students in California is an English-language learner). However, few state teacher preparation institutions offer bilingual authorization training programs. There’s been a steady decline in new bilingual authorizations in the state, with fewer than 700 teachers authorized in 2015-16.

Math and science teachers have been in short supply across the country, and LPI found that California is relying on substandard credentials and permits to fill the gaps. Between 2012 and 2016, the number of math and science teachers entering the field with full credentials dropped from 3,200 to 2,200, while the proportion of those teachers entering the field with substandard credentials or permits doubled, from 20 percent to almost 40 percent.

LPI found that enrollment in teacher preparation programs has steadily declined from 77,705 candidates in 2001-02 to 18,894 in 2013-14. There has been a slight uptick in the last couple of years, which could mean that prospective teachers are responding to the shortage. (A recent survey found that the majority of California voters would encourage a young person to become a teacher.) And the state has funded recruitment efforts and other training programs that are still in the early phases.

But those efforts won’t help address immediate demands. For the short-term, the LPI recommends that California offer scholarships or loan forgiveness to pre-service teachers who commit to teaching in high-needs fields and locations, utilize teacher residency models to help with retention rates, and remove barriers for retired teachers to re-enter the teaching field in shortage areas. (The last recommendation is a model that Virginia has used to curb shortages.)

Graphics courtesy of the Learning Policy Institute

More on Teacher Shortages: