Along a busy stretch of commercial roadway, an ordinary-looking office building serves as a sort of lending library for math and science education.

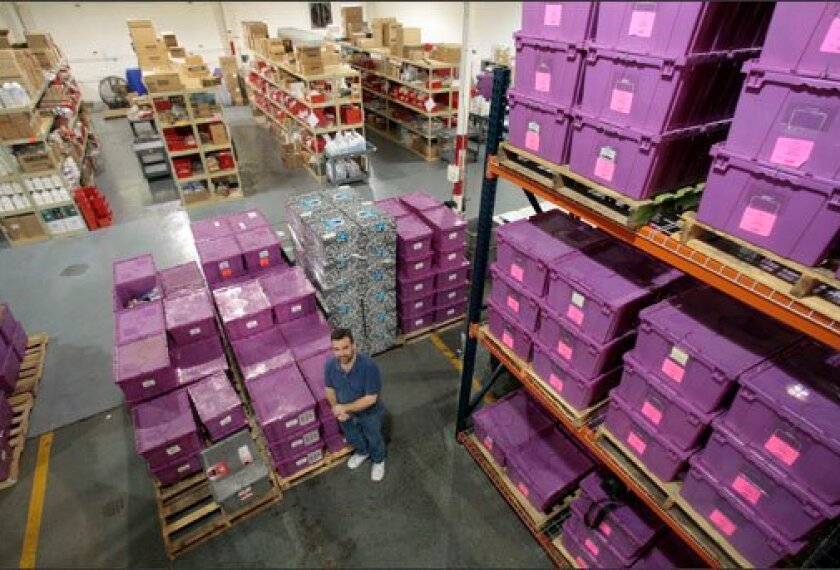

This facility, located in a suburb south of Birmingham, is one of 11 service sites for the Alabama Math, Science, and Technology Initiative, one of the largest and most ambitious state-run math and science programs in the country. The ground floor includes a sprawling warehouse, packed with math- and science-classroom equipment—graphing calculators, water-monitoring devices, beakers, flasks, even GPS units—which are shipped out on loan to schools, week after week.

Up a flight of stairs is a team of traveling mathematics and science “specialists,” who lend their expertise to schools, helping teachers with difficult content and lesson plans.

Giving schools access to classroom materials and supplying them with seasoned teachers are core elements of AMSTI, as the Alabama program is known. Launched in 2002 with the backing of corporate and university leaders, among others, AMSTI tries to raise students’ interest and achievement in math and science by offering schools a combination of professional development, instructional aid, and resources many could otherwise not afford.

When it was founded, only 20 schools were partners with AMSTI. Today, about 40 percent of Alabama’s schools, 575 in all, are taking part, and state officials hope to reach 100 percent participation eventually. More than 16,000 teachers have received training through the program so far. And participating schools have outperformed non-AMSTI schools, with the strongest results coming at early grades, according to external evaluations of the program.

Elementary schools taking part in the Alabama Math, Science, and Technology Initiative, or AMSTI, generally outperformed non-AMSTI schools on various measures, including the Stanford Achievement Test, according to an external evaluation.

SOURCE: Alabama Department of Education

AMSTI invites schools to enter into a type of contract, aimed at improving instruction.

Elementary, middle, and high schools seeking to take part agree to send all their math and science teachers and administrators through a two-week professional-development program for two consecutive summers. They must also designate lead math and science teachers within their schools, carve out time for teachers to plan lessons, and form partnerships with local businesses, among other requirements.

In exchange, teachers in AMSTI schools receive access to an organized inventory of classroom kits and equipment, which they are encouraged to order well in advance, though they can receive them on short notice, if necessary. Several thousand materials are available at each service site, as well as ongoing training and regular assistance from teacher-specialists. Some kits remain in schools all year; others are loaned out for periods lasting several weeks and refurbished by AMSTI staff members when they’re turned in.

On the Road

One of those charged with helping AMSTI teachers is Deborah O’Hara, who was hired as a math specialist in 2006 after 19 years in the classroom as a secondary math teacher. She now directs eight specialists in the AMSTI office in Pelham, which is affiliated with the nearby University of Montevallo.

Her office serves 39 schools in the surrounding five counties. When Ms. O’Hara was a specialist, she worked with 16 schools. Most weeks, she spent four out of five days on the road. She tried to reach each school at least once a month, some far more often, which she considers a typical schedule for the specialists.

All AMSTI math and science modules and classroom materials are designed to comply with the state’s academic standards in math and science. The materials and instruction offered through AMSTI emphasize “inquiry” lessons that encourage students to engage in problem-solving, through hands-on activities, and in-depth discussions of concepts and principles.

“I see AMSTI as helping students understand how math is used in the real world,” Ms. O’Hara explained. Too many students “memorize their way through math,” she said. “Then they get to the point where they’re not interested in math anymore, or ... the memorization won’t help them.”

Encouraging innovative and expert math and science teaching was one of the goals of Alabama officials when they began planting the seeds for AMSTI back in 1999. State leaders set out to create something similar to the Alabama Reading Initiative, a statewide program they credited with raising student performance in that subject.

State officials hired a full-time project director, Steve Ricks, to lead the new math and science venture, and brought together a blue-ribbon committee of K-12 teachers and administrators and business and university leaders to examine promising curricula and instructional methods. The committee studied other states’ math and science efforts and conducted an extensive survey of Alabama’s math and science teachers to gauge their instructional needs.

After the committee reviewed the evidence, its collective thinking was that “we’ve got a pretty good idea of what good math and science instruction looks like,” recalled Mr. Ricks, who now directs AMSTI. “Do we do that in our classes? No.”

Alabama math and science educators told the committee that the professional development they received on entering the field “didn’t sustain them beyond a few years” of teaching, and that they craved ongoing help, a point that resonated among industry and university officials, recalled Charles R. Nash, who served on that blue-ribbon panel. Teachers also cited the lack of basic math and science equipment in classrooms as a major shortcoming.

“They said,” If we don’t have the materials, we’re not going to be able to teach except the way we’ve been teaching,” said Mr. Nash, the vice chancellor for academic affairs for the University of Alabama System, which represents three public research universities in the state, including the flagship campus in Tuscaloosa.

That process yielded a series of recommendations for a statewide math and science program, which were melded together in AMSTI. The first AMSTI site was launched at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, with the help of a $3 million grant from NASA. Other locations followed.

Equipment and Ideas

From the Pelham office, AMSTI specialists are called out to schools to help teachers with math and science content or with designing lessons. Some educators ask specialists to team-teach a particular lesson with them until they get the hang of it. Others want to use equipment, such as graphing calculators, but need help.

It’s not always easy. Some teachers may be reluctant to seek or take advice, Ms. O’Hara said. Others believe the AMSTI specialists are making some sort of official evaluation of their teaching, which is not the case, she said.

When she first began working as a specialist, Ms. O’Hara struggled to keep up with teachers’ requests for help with so many, often very different, kinds of lessons. Near the end of her tenure as a specialist, Ms. O’Hara said, she was able to reduce those burdens by devising materials for the most oft-requested math lessons ahead of time and directing teachers to those.

One of the areas served by her AMSTI site is Jemison High School, about a half-hour drive south of Pelham. Ms. O’Hara has helped teachers there plan math lessons on ratios and proportions, exponential functions, and other topics.

Nanette Easterling, a math teacher at Jemison High, heard of an idea for presenting unit circles, a trigonometry concept, through AMSTI. During her precalculus class, Ms. Easterling unfurls a unit-circle game with large, colored paper cut-outs, showing the x and y axes, and has students play it on the floor. It’s a fun and simple way to translate textbook material, she says.

“So many of them look at the unit circle, and they’re just lost,” Ms. Easterling said. “When they see [the game] laid out on the floor, it makes sense to them.”

One of her colleagues, math teacher Robin Gray, used an AMSTI activity for her advanced geometry class. After handing her students wooden cubes, flashlights, and chart paper—all provided by AMSTI—she had them gather in a darkened school auditorium. They made hypotheses about the length of shadows, and tested them, later graphing the correlation between variables.

AMSTI’s popularity in schools like Jemison High and the achievement gains at its schools have helped persuade Alabama officials to devote more state spending to it. The program’s budget rose from $15 million in 2006 to $41 million in fiscal 2009.

“We’ve changed students’ attitudes,” Mr. Ricks said. “If a kid doesn’t enjoy math and science, why would they ever choose it as a career?”