At age 14, easygoing Ricky Bennett is wise to at least one thing: He doesn’t want to be like his dad.

‘Nativity’ schools, a little known network started by Jesuits, seem to have found a formula for helping students seemingly destined to struggle.

“When I grow older,” he says, “I want to be a better father than he has been to me.”

His dad, Ricky says, has been in prison for years, and he lost his mother to an asthma attack when he was 5.

Still, Ricky is lucky in at least two respects. He is growing up with a caring grandmother, and he is enrolled in a tuition-free private school at which even children with hardships tend to do well.

Ricky is one of 70 boys and girls attending the Mother Seton Academy here, one of 47 “Nativity” schools in the nation, a majority of which are run by Roman Catholic religious orders. The schools copy a model for middle school education started by Jesuits in 1971 at the Nativity Mission Center on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Hence the name.

|

Ricky Bennett Leaves Mother Seton Academy at dusk. He doesn’t particularly like the regimented school, but he’s been doing well and has been accepted by a Roman Catholic high school. |

The Nativity model isn’t well- known, even within private school circles, and as yet hasn’t been studied by researchers. But many Catholic educators have faith in the approach’s capacity to close the achievement gap between needy Hispanic or African-American students and their middle-class white peers. Nativity school graduates have gone on to attend such leading universities as Johns Hopkins, Cornell, Brown, and Northwestern.

Jesuit communities and other Catholic orders such as the De La Salle Christian Brothers, seeing a way to serve the poor, began to replicate the model in the 1990s. New Nativity schools continue to spring up each year. Most include religious teaching, though two of the schools are secular.

Visits to three Nativity middle schools that were each founded a decade ago—the Nativity Jesuit Middle School in Milwaukee, Mother Seton, and St. Ignatius Loyola Academy, also here in Baltimore—suggest the schools may be enacting a small miracle. They take in students who often lag one or more grades academically behind their peers, Nativity school educators say, and, within three years, prepare most of them to handle a rigorous high school curriculum.

The schools are a lesson in themselves: It can be done— achievement gaps can in fact be closed. But at the same time, Nativity schools show what an incredible amount of time and effort it takes for children who have fallen behind their peers, even at a young age, to get up to speed academically.

The schools typically cap enrollment at 70 and class sizes at 15. They have a long school day and school year. In Milwaukee, for example, students at Nativity Jesuit Middle School, which serves Hispanic boys from low- income families, return to school four nights a week for two hours to sit in straight rows of desks and do homework. Nativity schools enlist full-time volunteer tutors from religious community-service programs and from AmeriCorps, the federal national-service program, as well as part-time volunteers from the community.

Most of the schools don’t ease their task by selecting only the brightest students who apply, but they do choose students who are particularly motivated. And given the high cost of the small classes, among other reasons, the Nativity model would be hard to transplant to public schools. But the schools, if nothing else, demonstrate that a very intensive effort can benefit some of the nation’s most disadvantaged students on a very small scale.

“I don’t know anyone who is claiming we can transfer this model to American Catholic education, let alone American education,” says Michael J. Guerra, the president of the National Catholic Educational Association, based in Washington. “Nativity schools are starting with the premise that kids who have very poor prospects educationally can do well if they are put in the right kind of educational setting with the right kinds of adults. The setting has to be relatively small and both challenging and nurturing. The adults have to be committed to those kids and willing to work long hours.”

The social challenges for Ricky, who is biracial and in the 8th grade, aren’t unusual among students at Nativity schools. Many black students enrolled in the schools come from homes headed by a single mother, and some have a close family member who was murdered in street violence or is incarcerated. Latinos at Nativity Jesuit Middle School in Milwaukee feel pressure to get involved in the camaraderie and excitement of neighborhood gangs.

The students at Mother Seton, says Sister Mary Bader, the director of the school, must resist the negative enticements associated with being poor and living in a city.

|

“Turn away from sin and be faithful to the Gospel,” repeats Father Michael Heine as he rubs a cross of ashes on the forehead of Brittney Pilkerton, 12. The school community gathers for Mass five times each year on special religious occasions. |

“The attraction to sell and use drugs is a big challenge,” she says. “The consumer-culture mentality, which is telling our kids that what they own, what they wear, their appearance is important, goes against the values of education.”

Students, for instance, often hide their book bags under their coats outside of school so that they don’t appear too studious, Bader notes.

Safely inside Mother Seton, however, the students show they want to learn.

The 8th grade boys stay alert, for example, during the frequent math competitions devised by Sister Ann Claire Rhoads.

Ten boys, looking sharp in their navy and white school uniforms during a recent math class, march around their desks as Rhoads calls out problems and they work them in their heads. “Take a positive 16 and multiply it by a negative 2,” she says. “Add a negative 32 and divide your answer by a negative 8.”

Ten hands shoot up in the air.

Ricky guesses the answer is a negative eight, but he’s wrong.

Thirteen-year-old Raynault Wilburn offers his answer, a positive 8, and he’s right.

“Good job, Raynault,” one boy calls out, clapping his hands.

On a daily basis, Ricky unabashedly competes with one or two classmates in the 8th grade to answer as many questions in class as possible. He raises his hand so often in a language arts session that his teacher jokes he’s going to wear it out. A classmate of Ricky’s who sometimes joins the daily competition calls it “friendly rivalry.”

Ricky often shares his thoughts in class, which sometimes pulls the discussion off-course. In a history lesson about the Underground Railroad, his teacher talks a bit about the role of the Quakers in that 19th-century effort to aid escaped slaves. Ricky raises his hand: “Wasn’t [George] Washington a Quaker?” His teacher assures him he wasn’t. The teacher later projects a slide on the wall of Abraham Lincoln. Ricky observes that Lincoln looks as if he’s Amish.

During a religion class with Sister Rhoads on the same day, Ricky’s customary asides take on a more serious tone. Describing a passage of scripture in the Book of Mark, Rhoads talks about God as the “heavenly Father.” She remarks, “Some fathers are not a positive role model.”

“Like mine,” Ricky says to no one in particular.

Rhoads, a member of one of six religious communities that operate Mother Seton Academy, adds that if this is the case, when students think of their “heavenly Father,” they should picture someone else whom they admire.

Mother Seton’s students, 75 percent of whom are African-American, are primarily non-Catholic, as are those at St. Ignatius. But some Nativity schools, particularly those in Hispanic communities, serve a chiefly Catholic population.

|

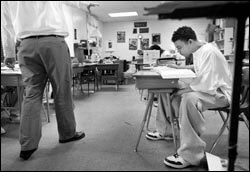

Nativity classes are more like seminars, with just a dozen or so students. Here, Ricky Bennett, right, and a few classmates listen to history teacher Matt Hill discuss the conflicts between North and South that led to the Civil War. |

Once a Nativity school accepts a student, the staff tries to keep him or her on board. Schools typically lose only one or two students from each graduating class that starts in 6th grade. Sometimes, students move away. Occasionally, the staff will expel a student who is disruptive or refuses to work hard, but that’s only after they’ve given the youngster extensive one-on- one help, administrators say.

The 8th grade class of boys at Mother Seton has lost three students in three years. The class gained one boy in the 7th grade, bringing the number of the current class to 10. The graduating class of 8th grade girls has lost one of the 12 girls who enrolled in 6th grade.

While most Nativity schools educate either boys or girls, Mother Seton enrolls both sexes, but teaches them in single-sex classes.

Most Nativity students say they like the special attention they’re getting.

At public schools, “they didn’t give us as much respect as they do here,” says Ricardo E. Arteaga, an 8th grader at the Nativity Jesuit Middle School, “Here, they help you if you don’t understand something.”

“Teachers get more in depth in your lives,” says Alexander Ruiz, an 8th grader at Baltimore’s St. Ignatius, which serves primarily African-American boys. “They want to help you learn.” At St. Ignatius, Headmaster Jeff R. Sindler greets each boy every morning at the door with a handshake.

Some students are well aware of their past failures.

Margaret Schlick, an 8th grader, says that when she entered Mother Seton Academy in 6th grade, “I didn’t know how to multiply. You were supposed to learn it in 4th grade.” With the help of tutors at the school, she learned both multiplication and division. “In the public school, they just fail you. They don’t help you pass,” Margaret says.

Students see the Nativity schools as strict in comparison with public schools.

“The public school is not hard,” says 11-year-old William Herd, a 6th grader at St. Ignatius. “You sit there and do your work. No matter what you do, right or wrong, you get credit for doing it. Here [at St. Ignatius], you have to mostly have the right answer to get it accounted for.”

He and two other 6th graders launch into explanations of various reward and punishment systems at St. Ignatius, such as how students can get assigned to Saturday study halls or be denied the opportunity to play sports, if they don’t adequately keep up with homework.

“In elementary school, I used to run the halls and talk out. I could get away with it because there were more kids in classrooms,” says Ferrell Wall, an 8th grader at Mother Seton.

|

Students at Mother Seton Academy have free tuition. But there is a price: about 10 minutes of labor each day cleaning the school. Jerrod Jones drew the short straw this week, getting the assignment to scrub toilets in the boys’ restroom. |

He says it was hard to adjust to Mother Seton’s rules. He has to eat all the food on his plate at lunch, for one thing, and if he receives a certain number of slips for not completing homework adequately, he has to go to Saturday detention.

“You have to have patience,” he says, but adds, “this school gave me a chance to do something with my life.”

Ricky Bennett is one of the rare Nativity school students who were previously enrolled in other private schools. He attended a Catholic elementary school on a partial scholarship.

It may be for that reason that Ricky doesn’t seem especially impressed by Mother Seton Academy. He says he doesn’t like school. He speculates that it might be better for him to go to a public school because it would make him tougher, pointing out that he lives in a household of women. All but one of his teachers at Mother Seton are women. The lanky boy, whose face shows faint signs of facial hair, has his own weightlifting bench at home.

At the same time, Ricky says about the academy: “I can’t complain. They treat me well.” He got A’s and B’s and one C- plus on his recent report card.

Whether he knows it or not, Mother Seton has paved the way for Ricky to get the kind of education that could put him on a strong footing in life. Last month, he was accepted by Mount St. Joseph High School, a Roman Catholic boys’ school operated by the Xaverian Brothers, one of the religious communities that run Mother Seton. The school offered him practically a free ride.

After seeing some promising alumni complete high school, only to end up stocking shelves in stores or take on other low-paying jobs, the staff members of Nativity schools have figured out they have to keep tabs on their graduates throughout high school and help them apply to colleges. Most graduates have parents who never set foot in a college classroom.

“A lot of our students— even though the high schools have counselors—don’t utilize resources,” says Ryan C. Hill, who is employed full time by St. Ignatius to support graduates of the school. “They want to fit in so bad, sometimes they don’t want to ask questions.”

Mother Seton Academy got a grant this year from a private foundation to pay for someone to oversee graduate support. It tapped Nicole Yeftich, who moved into the new position from a teaching job at the school. She’s now getting in touch with as many Mother Seton graduates as possible to help them with such tasks as preparing to take the SAT to filling out college- application forms.

Most Nativity schools haven’t kept good records of their success. But the sparse statistics that individual schools have collected look promising. For example, 70 percent of the first three 8th grade graduating classes of Nativity Jesuit Middle School went on to college. The St. Ignatius graduating class of 2002, on average, was reading at the 9th grade level at the end of 8th grade. Two years before, at the end of 6th grade, that class was reading only at grade level. About 85 percent of Mother Seton’s graduates enroll in Catholic, private, or public magnet college-preparatory high schools throughout the city rather than regular public high schools.

Parents of students at some Nativity schools are asked to pay a small amount of tuition, but the $10,000-a-student annual cost is largely financed by foundations and individual donors. Nativity school administrators say that if their students are accepted into private high schools, they can find donors to pay for whatever part of their tuition financial aid doesn’t cover.

|

Located in an old convent in downtown Baltimore, the school is coed. But the classes are separated by gender, so boys and girls mostly see each other only in the halls, at lunch, and at recess. |

The Nativity graduates who attend private high schools do seem to be able to handle the work, according to the Rev. John E. O’Brien, the principal of Cardinal Gibbons School, a Catholic middle and high school in southwest Baltimore.

But even if they are prepared academically, some Nativity graduates struggle to make the cultural shift. After three years in the cocoon of a Nativity school, where they share a similar background with other students and are showered with one-on-one attention, they find themselves at large private high schools where minority students are scarce. In those hallways, the experience for some former Nativity students is that “everyone is in a blue blazer and you feel just like a number,” says Hill of St. Ignatius.

Thirty-five of the Nativity schools more than a year ago formed a loose network, with headquarters in Baltimore, to raise money and share notes on effective practices. The 12 Nativity schools run by the De La Salle Christian Brothers formed a parallel network for the same purpose. Making sure that each Nativity school has the funds to pay for a full-time graduate support person is one of the goals of the Baltimore-based network, says the Rev. John J. Podsiadlo, the director of the network and the former headmaster of the first Nativity school in New York City.

As the Nativity schools gain a good reputation in many communities, a tension often develops over whether schools should lean toward taking in the brightest of students from low-income families.

“It’s an issue that arises from the [school] board,” says Podsiadlo. “They want the kids to shine and go to the top schools in the city. That was not the original goal, nor is it for the majority of the [Nativity] schools. The focus is on kids in need with different kinds of academic backgrounds.”

Sindler, the headmaster of St. Ignatius, says the board of his school, while intent on accepting students who are disadvantaged, has decided to admit only students who are of average or above-average ability. “Our board expects our kids to go to college,” he says.

Mother Seton Academy has not moved in this direction.

In the search for new students each year, says Sister Bader, “we’re not looking for 24 students who are highly motivated, college-bound, top-of the-class.”

Instead, she says, “we’re looking for kids who might get lost in the system.”

Coverage of urban education is supported in part by a grant from the George Gund Foundation.