As Congress wrestles with rewriting the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, it has an opportunity to change the way we hold high schools accountable for their work with students. A paper that slipped by with too little notice earlier this month lays out an interesting option.

In “Mind the Gap,” Chad Aldeman argues that judging high schools primarily on their test scores and graduation rates, as we have done under No Child Left Behind, creates a perverse incentive to hustle more students over the threshhold with inadequate skills. Even worse, he argues, those data don’t really tell us what we need to know about our schools: Are they preparing students well for what lies next?

Aldeman, an associate partner at Bellwether Education Partners, uses data from Tennessee to remind us of something we’ve long known: Many high schools with pleasing graduation rates and test scores have less-than-pleasing college-enrollment rates. With graduation numbers at the heart of high school accountability, Aldeman argues, we’re not measuring many things we profess to care about, such as growth in student achievement, and success in college and work.

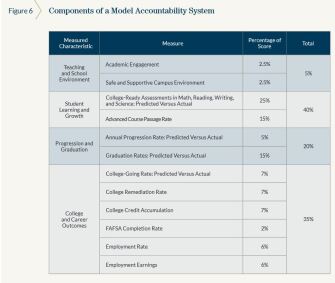

The accountability scenario Aldeman offers in his paper aims to change that. By this metric, only 20 percent of a school’s rating would depend on data related to its graduation rate, and a slice of that would focus on how well it moves students through school year to year. Thirty-five percent of a school’s rating would be based on how well its preparation paid off in jobs and college enrollment and how well students did in those settings. Forty percent would depend on students’ performance on tests and in advanced high school courses, and that chunk would have to consider how well a student performed against himself: how his score looks when considered along with his attendance, class grades, and previous test scores.

Data capabilities have evolved sufficiently in recent years to allow states to build systems like this, and with U.S. Department of Education waivers in place, nearly every state has the freedom to build an accountability system that rewards and pressures schools for the things that really matter, Aldeman argues in the paper. (As we know, however, most states didn’t take advantage of the flexibility to do anything profoundly different.)